Tactics of Repression

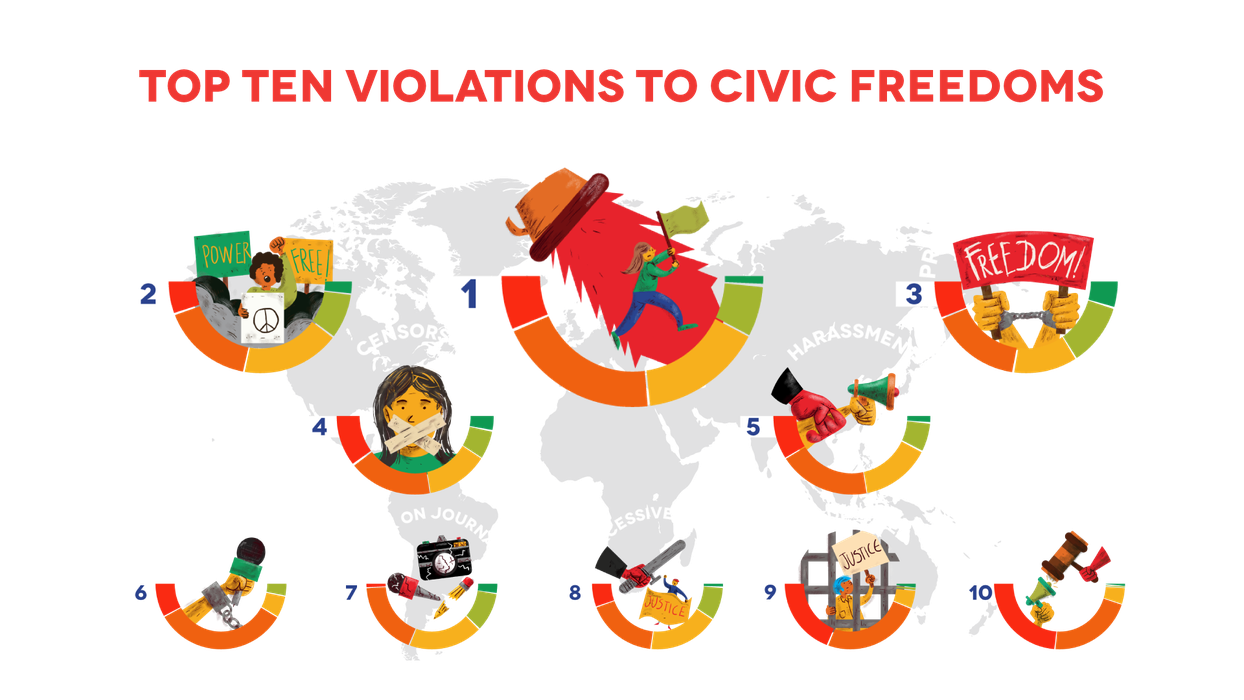

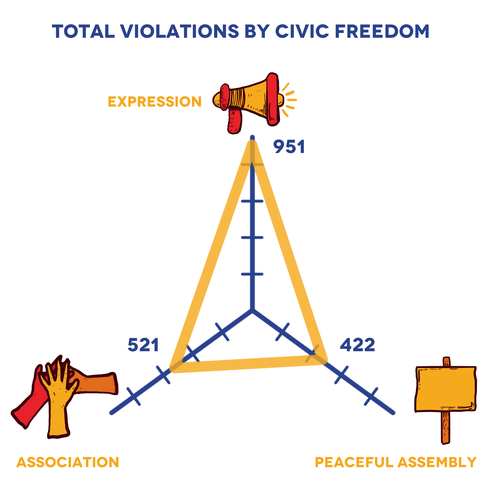

Of the three freedoms tracked on the CIVICUS Monitor, freedom of expression is most commonly targeted by state and non-state sources, accounting for around half of the total violations recorded. Intimidation was the most featured violation during the reporting period, with almost 65 per cent of intimidation incidents targeted against journalists and media outlets. Other freedom of expression violations recorded are censorship and detention of journalists.

States also regularly violate the right to freedom of peaceful assembly through the detention of protesters and the use of excessive force. Other commonly reported violations on the CIVICUS Monitor are incidents of harassment against human rights defenders (HRDs) and journalists and the detention and prosecution of civil society activists.

Freedom of expression in decline

Freedom of expression is essential for transparency, accountability and participation, which are the pillars of good governance and participatory democracy. As such, it has become a target, particularly for many authoritarian governments that seek to suppress dissent. This analysis is in alignment with other assessments that show that freedom of expression is the aspect of democracy undermined the most in autocracies.

The CIVICUS Monitor documented over 950 violations of the right to freedom of expression during the reporting period. According to our analysis, governments use a range of tactics to silence critical voices and free speech, from intimidation of journalists and media outlets to arbitrary detention and attacks on journalists.

Globally, intimidation is one of the most common tactics used to restrict civic freedoms. Intimidation occurs in a range of forms, including police summons for questioning, threats of arrests and prosecution, public vilification, raids on the homes and offices of HRDs and journalists and online or offline threatening messages from both state and non-state sources. Intimidation was reported in at least 107 countries. Intimidation is particularly used to deter journalists and media outlets from reporting on critical issues, covering protests or speaking out. Our data shows that intimidation is being used more often by states, particularly police and security forces.

A few cases exemplified this trend. In Indonesia, an improvised explosive device was detonated outside the house of Papuan journalist Victor Mambor from independent news website Jubi. He has faced ongoing intimidation over his reporting on human rights issues in the Papuan region, home to an independence movement. In Guinea, soldiers stopped two journalists – Aliou Maci Diallo of Guinée Info and Mamadou Macka Diallo of Guinée 114 – in Bambéto, Conakry. They insulted and threatened them while they reported. In Tunisia, police raided and searched the house of Mosaique FM head Noureddine Boutar and arrested him.

Intimidation is often used to prevent the continuation of critical investigation or the publication of information. In Mexico, the police detained an independent journalist after he attempted to film police officers who threatened him and falsely accused him of a traffic violation. Kenya's media regulatory authority threatened to revoke the broadcast licences of six local media outlets for allegedly ‘violating the programming code’ in their coverage of protests.

Censorship is also commonly used to restrict freedom of expression. The CIVICUS Monitor documented this violation in at least 86 countries. Censorship can take many forms, such as bans or suspension of media outlets, bans on the publication of particular content online or offline and internet access shutdowns during critical periods, but the objective is the same: to prevent journalists doing their work and citizens speaking out, expressing dissent and accessing timely information, with dire consequences for the functioning of a democracy. Troublingly, censorship is a tactic used in several countries regardless of the underlying level of respect for civic freedoms.

The use of national regulatory bodies to ban media outlets permanently or temporarily is a common form of censorship across regions. Voice of Democracy, one of the few independent media outlets left in Cambodia, lost its media licence and was shut down by the Ministry of Information for an article allegedly slandering the government. In Egypt, two news websites, Masr 360 and Soulta 4, were blocked, reportedly in relation to the content they publish.

Despite legal and policy gains achieved globally to recognise LGBTQI+ rights, and linked to a backlash that is seeing the criminalisation of LGBTQI+ people and groups in several countries of Africa, some governments actively banned or prevented the dissemination of books, movies, or publications with LGBTQI+-related content. Cameroon’s national media regulator, the National Communication Council, suspended TV channel Canal+ Elles on accusations of broadcasting programmes that ‘convey obscene practices and homosexual tendencies’. In February 2023, authorities in Kenya ordered one of Nairobi’s leading bookstores, Text Book Centre, to stop selling the teen book ‘What’s happening to me’, as it states that ‘it is possible to fancy both girls and boys’

Hostility towards LGBTQI+ people and groups was also documented in other regions. In Lebanon, the Minister of Interior and Municipalities banned two LGBTQI+ events scheduled for November 2022. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Banja Luka police banned an indoor movie screening and panel discussion on LGBTQI+ rights. On the scheduled day of the event, dozens of masked people armed with metal bars and bottles attacked the organisers at their secret meeting location.

While not documented exclusively in the region, a common trend in Europe is for governments to prevent journalists covering protests and critical issues such as the treatment of migrants and refugees. In Spain, several journalists were banned from accessing a Madrid City Council viewpoint to take pictures of a protest staged by healthcare workers. In Italy, the head of the cabinet of the prefecture of Salerno prohibited journalists from filming or photographing migrants arriving in the port city.

Emboldened by widespread impunity, states and non-state sources have used more violent tactics to suppress dissent. The CIVICUS Monitor documented attacks against journalists in at least 66 countries and arbitrary detention in 67.

Attacks against journalists were documented both in countries with strong civic space protections and those with more repressed civic space. In Nigeria, at least 10 unidentified people punched and used sticks to beat a TV crew from Arise TV – correspondent Oba Adeoye, camera operator Opeyemi Adenihun and driver Yusuf Hassan – after the crew used a drone at voting stations in Lagos state. In Sudan, freelance journalist Shamael Elnoor was beaten by military forces with rubber hoses while covering a protest. In the USA, a reporter with the Binghamton Press & Sun-Bulletin was pepper-sprayed by police while covering a protest in Johnson City, New York. In Maldives, a Channel 13 media worker and Sangu News journalist were physically assaulted by Maldivian police while covering an opposition protest in Malé’s Republic Square. In Germany, officers beat and pepper sprayed a journalist covering an environmental protest in Lützerath, despite him being accredited with police.

In comparison, the arbitrary detention of journalists is most commonly used in repressed countries and rarely documented in those rated as open or narrowed.

In Uganda, police officers arrested freelance journalist Andrew Arinaitwe while covering a story on claims of sexual abuse by teachers in Ugandan boarding schools, including at Kings College Budo. In India, Anjay Rana, 19-year-old reporter for the privately owned newspaper Moradabad Ujala from Uttar Pradesh state, was arrested after he questioned a local minister from the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party about unfulfilled promises made by the government.

In Poland, while covering a climate protest, photojournalist Maciej Piasecki was violently arrested, had his camera confiscated and was taken to a police station for questioning for ‘violating a police officer's bodily integrity’; the officer fell while dragging Piasecki to the ground by the neck. Moroccan security forces arrested blogger Yassin Benchekroun on charges of ‘insulting legally organised and other constitutional institutions and disrespecting judicial decisions’.

Right to protest: a continuous target

People protest to express their dissent, raise awareness and mobilise for change. In many countries in 2023, people took to the streets in response and opposition to government actions, to raise awareness about climate change and demand action, to demand better working conditions and to protest against the increased cost of living, among many other reasons. The common denominator is the response by authorities to the protests.

The right to peaceful assembly is usually exercised when other rights are being violated. People take to the streets to demand rights, yet states usually ignore these rightful demands and instead disrupt protests. Those who take to the streets to show disapproval of government political decisions or those demanding action on climate and the environment are most commonly repressed.

According to CIVICUS Monitor data, states and non-state sources have used excessive force and the detention of peaceful protesters as the most common tactics to disperse protests. During the reporting period, more than 200 protests were disrupted by authorities. Protests were disrupted in no less than 85 countries around the world. In at least 69, excessive force was used as a tactic to prevent people fully exercising their right to peaceful assembly. In almost 40 per cent of disrupted protests, authorities used both excessive force and the arbitrary detention of protesters.

In Bangladesh, there have been mass arrests of opposition supporters taking part in protests and fabricated cases have been filed against them. Police and mobs of ruling party supporters have also attacked protesters with live ammunition, teargas, rubber bullets and sticks. In Sri Lanka, police used water cannon to disperse ethnic Tamil protesters in January 2023, as they rallied against President Ranil Wickremesinghe's visit to their district.

In Bolivia, police repressed a protest from a group of HRDs who gathered to demand respect for democracy and the defence of human rights. In Hungary, when students, teachers and opposition members of parliament (MPs) gathered in Budapest to protest against the proposed ‘revenge law’ that places new restrictions on teachers, police intervened aggressively to prevent them, dragging away several MPs and using teargas to disperse the protest.

Numerous instances in the Africa region highlight the challenges faced by opposition groups and leaders when attempting to voice dissent. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), security forces dispersed a peaceful protest organised by a coalition of opposition parties, causing injuries to at least 30 people.

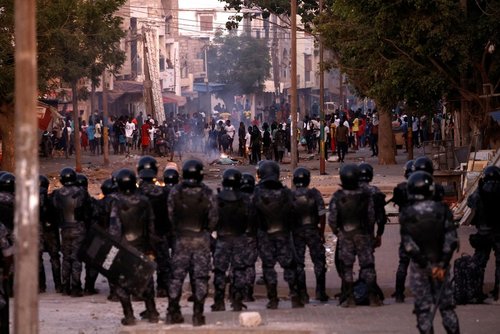

In Chad, the authorities prohibited a planned protest by the political party Mouvement Révolutionnaire pour la Démocratie et la Paix (Revolutionary Movement for Democracy and Peace), citing potential risks to public order. In Senegal, the conviction of opposition leader Ousmane Sonko led to deadly protests and clashes with security forces.

An ongoing trend is the repression of environmental protests. In Panama, mass protests erupted in October following the approval of Law 406, which granted mining rights to the Minera Panamá copper mine. The police used teargas and weapons to disperse the demonstration and arrested 30 people. Extinction Rebellion activists in the Netherlands protested against fossil fuel subsidies, resulting in numerous detentions. In Australia, Blockade Australia activists faced arrests for protests against climate inaction, highlighting discontent over the government’s response to the climate crisis.

In Vietnam, police armed with batons and shields dispersed dozens of members of the Ede ethnic group who were attempting to block a drainage project they feared would discharge waste water into a lake they depend on. Similar situations were documented in Argentina, Belgium, Germany, New Zealand and the Philippines.

Concerningly, 18 per cent of protests disrupted with excessive force resulted in the killing of at least one protester. In Peru, in protests that erupted after the dismissal of President Pedro Castillo in December 2022, over 60 people died in clashes between the police, military and protesters. In Senegal, dozens were killed after protests sparked by the indictment and arrest of Ousmane Sonko.

In the face of this repression, people continue to mobilise to defy restrictions and make their voices heard. In Afghanistan, women continue to protest even when facing brutal responses by the Taliban. In August 2023, a small group gathered to demand the right to education ahead of the second anniversary of Taliban rule. In Myanmar, activists continue to mobilise against the military junta. In Iran, after the 2022 severe crackdown by the authorities on widespread protests, women continue to fight for their rights, even while in detention: in September 2023, courageous women prisoners of conscience staged a sit-in at