Freedom of Peaceful Asseembly (COVID-19)

Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and the COVID-19 pandemic: A snapshot of protests and restrictions

The CIVICUS Monitor is producing periodic research on the state of civil liberties during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is the fourth installment which provides a snapshot of trends and case studies related to the right to freedom of peaceful assembly.

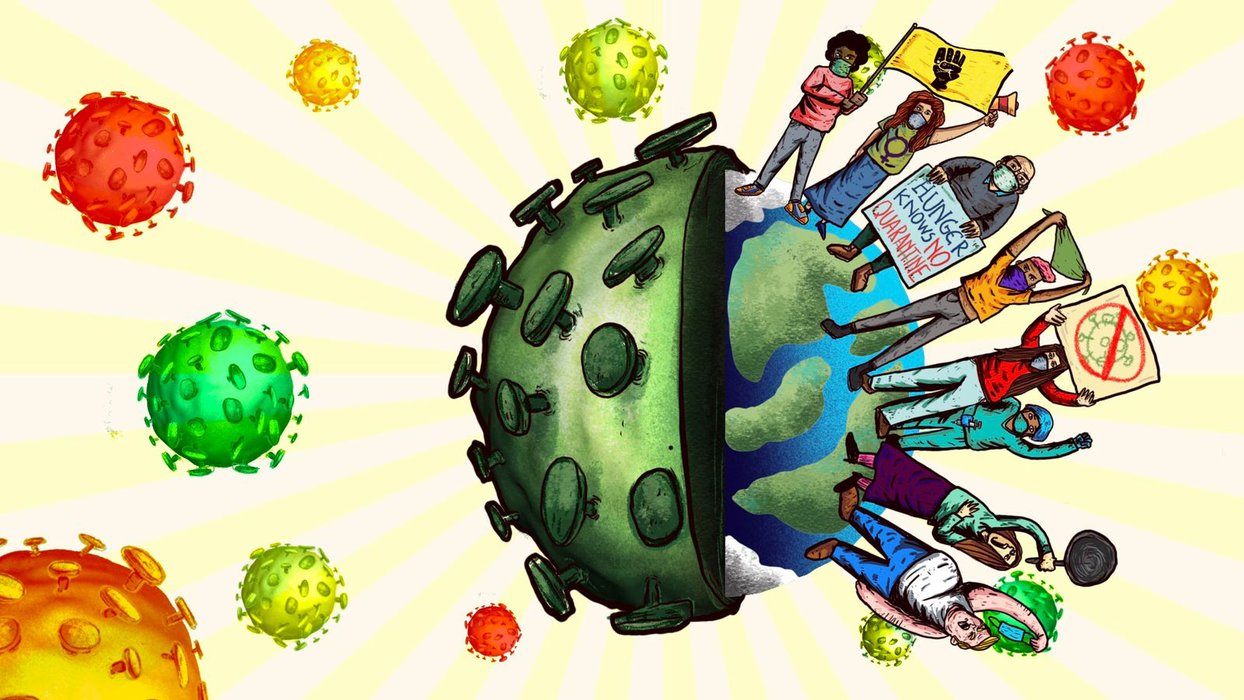

Peaceful assembly is a fundamental right, and protests offer an incredibly powerful and successful means of advocating for and defending other vital rights. The power of this right was shown during the pandemic as people continued to take to the streets in all regions of the world. While the COVID-19 pandemic has further challenged and threatened the right to peaceful assembly, people continued to take to the streets to voice their concerns related to COVID-19 and demand other important rights.

Since March 2020 when COVID-19 was declared a pandemic, governments around the world imposed strict lockdowns, with public assemblies banned or limited. International human rights law makes clear that while limitations on rights are permissible during a health emergency, these limitations have to be necessary, proportionate, non-discriminatory and in place for a limited period of time. However, as highlighted in CIVICUS’s 2020 report People Power Under Attack, some governments have gone beyond this and used the pandemic as a pretext to further restrict civic freedoms. The United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur on the Rights to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and of Association, Clement Voule, warned that the pandemic must not be used as a pretext to suppress rights in general or the rights to the freedoms of peaceful assembly and association in particular.

Restrictions on public gatherings during the pandemic initially brought some mass protest movements to a halt. This was seen in countries including Chile, Czech Republic, India and Lebanon. In some countries, including Hungary, Italy, Palestine and Singapore, movements adapted and people began staging solo and socially distanced protests, including protests on their balconies and through online platforms, including social media. However, after some time, many people returned to the streets to protest during the pandemic, driven at times by concerns related directly to the pandemic and often also to express urgent demands related to fundamental rights.

The pandemic has exposed and further worsened global inequalities. Correspondingly, many of the protests that took place during the pandemic, as documented by the CIVICUS Monitor, highlighted the prevalence of social and economic inequalities.

This brief covers civic space developments related to the right to the freedom of peaceful assembly in the context of COVID-19 from the period February 2020 to January 2021. It is compiled from data from our civic space updates prepared by activists and partners on the ground. We examine the types of protests that were staged during the pandemic and the restrictions on the right to the freedom of peaceful assembly.

Protests continue during COVID-19

What led people to the streets?

During this period, people staged protests on a range of issues, including protests against COVID-19 confinement measures and protests to call for an end to COVID-19 measures due to hunger, poverty and unemployment. Others took to the streets to fight against racial injustice, gender-based violence, police brutality and poor political leadership.

Protests on police brutality, which called out entrenched racism, discrimination and colonialism, occurred in every corner of the globe. Women took to the streets over increased incidences of domestic violence during the pandemic, while others called on their governments to maintain protection mechanisms that help prevent violence against women. Women staged pro-abortion protests, while LGBTQI+ people protested against far-right governments adopting anti-LGBTQI+ laws that undermine rights. People also staged anti-government protests, demanding constitutional change, electoral reforms or changes in political leadership.

Protests against racial injustice and police brutality featured prominently during the pandemic. The murder of George Floyd, a Black man, by the Minneapolis police on 25th May 2020 sparked massive protests against police brutality in the USA, under the banner of Black Lives Matter. These protests spread throughout the globe, including in Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, The Gambia, Ghana, Sri Lanka and the UK.

Protests focusing on gender justice, equality and reproductive rights took place in many countries, including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia, Mexico, Poland, Singapore and Turkey. People protested to demand sexual health and reproductive rights, for an end to gender-based violence and for LGBTQI+ rights.

Protests related to elections, governance and political and legislative developments took place in countries such as Cameroon, Côte d'Ivoire, Guinea, Haiti, Iraq, Lebanon, Mali, Nepal, Niger, Peru, Philippines, South Africa, Syria, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. During these protests people called out corruption, poor governance and leadership and demanded basic service delivery.

COVID-19 related protests

During the pandemic, people also took to the streets to protest over COVID-19-related developments, from the government's handling of the pandemic and lockdown measures to the lack of economic relief and concerns over labour rights.

Protests on labour rights or sector-led protests were documented in at least 42 countries. The conditions of healthcare workers were put under the spotlight during the pandemic, with many hospitals fighting to cope with the surge in COVID-19 infections. In several countries, including in France, Kosovo, Lesotho, Malaysia, Mexico and Pakistan, nurses, doctors and healthcare workers staged socially distanced protests to demand better labour conditions, including more personal protective equipment (PPE) and an improvement in their working hours and salaries. In Spain, workers asked the question, “Who will look after the people who look after you?” to highlight the challenging working conditions in the sector.

Other sectors, such as hospitality, including cafes, restaurants and bars, also staged protests, including in Bulgaria, Italy, Kosovo, Mexico and Montenegro. Some in the hospitality sector staged protests over the lack of financial support from governments during the pandemic, while others called for the reopening of their sector.

In countries such as Cambodia, Laos, Maldives, the Netherlands, Panama, Peru, Taiwan and Tajikistan, workers in industries including garment and technology manufacturing, logistics, transport, construction and mining staged protests. These protests were staged in relation to a range of issues including the non-payment of salaries, lack of COVID-19 workplace protection measures, inhumane working conditions and the lack of employment during the pandemic.

In countries including Croatia, Mexico and Uganda, informal traders and small businesses, which were particularly impacted on during the pandemic, called for urgent government relief. The lack of employment and rising unemployment rates as a result of the pandemic were also key labour rights issues raised during protests.

Protests on other economic, social and cultural rights took place in at least 33 countries. Some parents, teachers and students called for the closure of schools during the pandemic, improvements in online learning and safety measures, while others called for the reopening of schools and universities. These protests were staged in countries including Albania, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Greece, Japan and Serbia.

Protests against food insecurity, poverty and unemployment took place in countries including Afghanistan, Chile, Honduras, India, Kazakhstan, North Macedonia, South Africa and Venezuela. “Hunger does not go into quarantine” – a message used during one protest in Colombia – pointed to the harsh economic consequences experienced by many people during the pandemic, particularly people in excluded groups.

Related to this, in countries including Bolivia, Cambodia and Uganda, people protested over the economic crisis that has worsened due to the pandemic and over the lack of relief measures and policies, such as social grants, during the pandemic.

Protests focusing on other pandemic demands were documented in at least 19 countries. People called for the rights of excluded groups, such as migrants, refugees and prisoners, to be protected and respected during the pandemic. In countries such as Egypt, Iran, Italy, Maldives, Morocco and Nicaragua, several protests called for the release of prisoners and detainees who were exposed to increased risk of COVID-19 infection due to poor conditions in facilities, where social distancing is almost impossible.

The protection of the rights of migrants and refugees during lockdowns was also a key demand made during some protests, including in Mexico, Nepal, Rwanda and the USA. Police brutality during the enforcement of confinement measures also sparked protests in countries including Kenya and Mexico.

In countries such as Brazil, Czech Republic, Guatemala, Malaysia, Mexico and Slovenia, anti-government protests were staged, calling on governments to be held accountable or to step down as a result of poor pandemic response.

Anti-confinement protests were documented in at least 59 countries. In countries including Argentina, Iraq and Malawi, people protested against the serious impact of confinement measures on their livelihoods. These protests highlighted the stark inequalities experienced by people during the pandemic, which were further exacerbated by governments that failed to ease economic burdens.

In some instances, people protested against the application of COVID-19 measures such as mask wearing, social distancing and vaccines. These included protests that spread disinformation and conspiracy theories about the virus and the pandemic. These protests took place in countries including Australia, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Germany and the USA.

Restrictions on protests

Violations of the right to the freedom of peaceful assembly can take many forms, from protest bans, time and place restrictions on protests, restrictive laws, excessive use of force by the authorities, the detention of protesters and the killing of protesters.

The use of excessive force by security forces during protests occurred in at least 79 countries, including Brazil, Bangladesh, Ecuador, France, Indonesia, Kenya, Montenegro and Tunisia. In the context of emergency measures, the authorities may use force only when strictly necessary and to the extent required to carry out their duty, and only when less harmful measures have proven to be clearly ineffective. At all times, including during a state of emergency, the authorities must comply with relevant international norms and standards.

In Lebanon, following the Beirut port explosion on 4th August 2020, thousands took to the streets to demand political accountability and to protest against the worsening economic situation. Videos documented security forces firing teargas at the protesters who gathered in front of the parliament building on 6th August 2020, days after the explosion. On 8th and 9th August 2020 riot police fired teargas at peaceful protesters and shot at them with live ammunition and rubber bullets. During these protests, 728 protesters were injured.

The use of excessive force has sometimes included lethal force, leading to the killing of protesters, documented in at least 28 countries. The UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms outlines that lethal force is strictly only allowed when trying to preserve life, and force needs to be proportional to the offences committed.

In Nigeria, on 20th October 2020, security forces used live ammunition against #ENDSars protesters in Lagos, killing at least 12 people. Protesters had been protesting against police brutality for two weeks prior to the shooting, demanding the disbandment of the notorious Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) unit of the Nigerian police, which has been frequently accused of torture, ill-treatment, extortion and extrajudicial killings by human rights groups. The protests, that came with intensive use of social media, also raised wider grievances of bad governance and a lack of accountability in Nigeria. Among the other countries where the use of lethal force was seen were Afghanistan, Belarus, Guinea, Iraq, Uganda, the USA and Venezuela.

In at least 100 countries globally, law enforcement officers detained protesters, often on the grounds of failure to adhere to COVID-19 measures or other laws related to peaceful assemblies. In Thailand, during 2020, the youth-led pro-democracy protest movement increasingly articulated demands for reform of the monarchy. However, the authorities have arrested or charged at least 173 people in relation to their protest activities since the beginning of 2020 under an array of repressive laws. The detention of protesters also took place in countries such as Azerbaijan, Bolivia, China, Greece, Lebanon and Zimbabwe.

Recommendations to governments

To respect the freedom of peaceful assembly, governments should:

- Ensure that all laws and regulations limiting public gatherings based on public health concerns are necessary and proportionate in light of the circumstances. The public health emergency caused by COVID-19 must not be used as a pretext to suppress rights in general or the rights to the freedom of peaceful assembly in particular.

- Ensure compliance with international frameworks that govern online freedoms by refraining from imposing online restrictions, including restrictions on the internet during protests, and allowing protesters to access information at all times.

- Ensure that any limitations imposed are removed and that full enjoyment of the rights to the freedom of peaceful assembly is restored when the public health emergency caused by COVID-19 ends.

- Publicly condemn at the highest levels all instances of arbitrary arrests and the use of excessive force by security forces in response to protests.

- Conduct immediate and impartial investigations into all instances of arbitrary arrests and use of excessive force by security forces in the context of protests.

- Drop charges and release all protesters and human rights defenders prosecuted for exercising their right to the freedom of peaceful assembly and review their cases to prevent further harassment.

- Provide recourse to judicial review and effective remedy, including compensation, in cases of unlawful denial of the right to the freedom of peaceful assembly and use of excessive force by state authorities.

- Review and, if necessary, update existing human rights training for police and security forces, with the assistance of international experts and independent civil society organisations, to foster more consistent application of international human rights standards, including the UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms.