Americas

Rating Overview

Civic space conditions in the Americas continue to deteriorate. In 2023, Venezuela joined Cuba and Nicaragua in the list of countries rated as closed, where civil society faces severe consequences when expressing dissent and a climate of impunity prevails.

Out of the 35 countries in the Americas, civic space is considered closed in these three countries, repressed in five and obstructed in six. Thirteen countries in the Americas are rated as narrowed, and eight have open civic space.

Over the past year, many states intensified their control over civic space by abusing punitive powers against HRDs and journalists, resulting in significant setbacks for the civic freedoms that underpin democratic values. The consolidation of authoritarian governments, such as Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela, starkly exemplifies this trend. Until 2021, only Cuba had been rated as closed in the Americas. In 2021, Nicaragua joined this category, following a crackdown on civil society since 2018.

Although Venezuela was rated as repressed over recent years, the cumulative impact of repressive measures and systemic crackdowns on HRDs and dissenting voices had finally led to a downgrade to the closed category. These measures have in practice suspended fundamental civic freedoms, leaving civil society in a precarious state of vulnerability.

Several censorship mechanisms are part of a strategy to persecute activists and limit speech criticising the government. For instance, in May 2023, a radio opinion programme decided to cancel transmission due to pressure after reporting on a scandal involving the manager of Venezuelan state-owned oil company PDVSA Gas Comunal in Barinas.

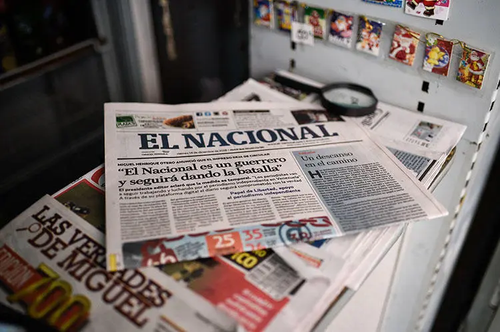

Regulatory uncertainty over the media is a control mechanism that led to the closure of 81 radio stations in Venezuela in 2022 and at least five during the first part of 2023. This figure makes 2022 the period with the highest number of closed stations in the last two decades. Further, in the past nine years, over 60 Venezuelan newspapers ceased circulation indefinitely due to government control, a lack of funds or the inability to purchase sufficient paper to print their editions. TV networks have been forced to self-censor or close, and 10 foreign networks have been expelled from the country.

The right to association is also at risk in Venezuela. In January 2023, the National Assembly approved on first reading a draft NGO Law that could be used to control, restrict and potentially criminalise and close CSOs working in the country. Similar legislation has been used in other countries, such as Nicaragua, to close down hundreds of CSOs and arrest opposition leaders, journalists and HRDs.

In March 2023, Venezuela’s National Assembly adopted the International Cooperation bill on its first reading. Similar to the draft NGO Law, this bill, initially introduced in May 2022, raised concerns due to the imposition of arbitrary limitations on the operation of civil society bodies. These bills are highly restrictive and could potentially lead to the arbitrary suspension and dissolution of CSOs.

The legal situation for CSOs in Venezuela is already precarious. Under the current legal framework, some reports estimate that 28.3 per cent of CSOs operating in Venezuela have been unable to obtain legal status. Meanwhile, almost 55 per cent of registered organisations have reported facing obstacles when changing their boards of directors or undergoing similar administrative changes. In a more recent development, on 4 August 2023, the Supreme Court of Justice ordered the intervention of the National Committee of the Venezuelan Red Cross. As a precautionary measure, it established an ad hoc restructuring board with the authority to manage the organisation’s assets and convene internal elections.

Civic Space Restrictions

In the Americas, the most frequent violations documented during the reporting period were intimidation, attacks on journalists, harassment, killings of HRDs and the disruption of protests.

Intimidation and harassment against journalists and HRDs

Over the past year, intimidation and harassment were two of the most widespread civic space violations documented, observed in at least 24 countries in the Americas. Intimidation tactics instil fear and can serve as a tool to dissuade journalists and HRDs from persisting in their work. Harassment has the same strategy and goal but is characterised by the repeated targeting of CSOs and media outlets. Often interlinked, these practices involve a wide range of tactics such as threats, smear campaigns and recurrent police summons.

In the face of repressive and intimidating practices, a concerning trend persists in the Americas where HRDs and journalists find themselves often treated as adversaries of the state, despite their entitlement to specific legal protections. The weakening of democratic institutions exacerbates these civic space violations, along with the erosion of judicial independence and high levels of impunity in cases involving human rights violations.

For instance, in El Salvador, intimidation continues to be frequently used against independent media. In October 2022, at least 12 people from Radio Suchitlán, a community radio station, reported intimidation and surveillance by local political figures. Unidentified people inquired about the residence and working hours of staff, mostly young volunteers. Elected in 2019, President Nayib Bukele has actively spearheaded a ruthless crackdown on criminal gangs in recent years, imposing a state of emergency and suspending fundamental rights. This has led to severe restrictions on journalists’ work.

In Cuba, authorities employed harassment and surveillance tactics to prevent HRDs raising concerns about the human rights situation. This was prevalent during the G77+China Summit, held in Cuba, with at least 134 acts of repression documented, including police surveillance that frequently commenced a day before the event.

Journalists were frequent targets of threats while covering crime and corruption cases. In Mexico, several journalists in Sinaloa reported being threatened, having their cars and work equipment stolen or damaged and being forced to flee during a violent series of attacks in the region. In Venezuela, investigative journalist Ronna Rísquez and her family members faced threats following the publication of her new book on the Tren de Aragua criminal gang. Released in early 2023, Rísquez’s book details the rapid rise of the criminal group, implicated in extortion, murder, drug trafficking and people smuggling.

Women’s organisations are often particularly targeted with harassment. From March to August 2023 in Guyana, the Red Thread Women’s Organization received several threatening emails due to its opposition to key clauses in the country’s oil contracts with ExxonMobil. The group has also actively called for the resignation of Local Government and Regional Development Minister Nigel Dharamlall, who faces accusations of raping a 16-year-old Indigenous girl. In November 2022, Nicaraguan police and public employees harassed four women’s rights defenders and local leaders during municipal elections held without significant opposition.

Police summons for interrogations, threats of arrests and persecution and smear campaigns are among the tactics used to intimidate journalists and HRDs. In January 2023, officers of Venezuela’s investigative police unit took El Nacional news editor José Gregorio Meza and human resources manager Virginia Nuñez to the Attorney General’s Office for questioning. They were investigated for crimes under the ‘Anti-Hate Law’, which has often been used to criminalise dissent.

In May 2023 in Venezuela, Oscar Costero and Santiago de Viana, both Wikipedia editors, were stopped and questioned by police while trying to renew their passports. The police informed Costero for the first time that there was an investigation being conducted on him. Venezuelan authorities have frequently used administrative, legislative and judicial measures as repressive practices.

Attacks on journalists

The right of journalists to work safely and without fear is integral to freedom of expression, but they often experience threats and physical and verbal attacks, with most incidents going unpunished. Since 2018, attacks on journalists have repeatedly topped the list of civic space violations in the Americas, pointing to the persistence of a hostile environment for the media and the great personal risks journalists can face for doing their crucial work. The CIVICUS Monitor documented physical attacks on journalists in at least 15 countries of the Americas.

State and non-state forces have attacked journalists and others involved in reporting on protests. In February 2023 in Argentina, the Buenos Aires police violently repressed journalists reporting on protests against power cuts in the Villa Lugano neighbourhood. In Suriname, media workers were injured and their equipment destroyed or stolen during a protest in Paramaribo to denounce austerity measures, including the elimination of subsidies, in the context of high inflation. In the USA, police pepper-sprayed a journalist covering a protest demanding justice for the police killing of Tyre Nichols and the arrest of Hamail Waddell.

Since December 2022, journalists and media workers have reported at least 94 cases of attacks during widespread anti-government protests in Peru, predominantly perpetrated by police and military forces.

In Brazil, cases have been reported of public officials engaging in verbal and physical attacks on journalists. For example, in January 2023, the Mayor of Pelotas in Rio Grande do Sul began a speech by verbally attacking journalist Rafaela Rosa of Diário Popular. This attack stemmed from a report published that day outlining plans to create and modify positions and rules of the legislature. A month later, one of the city hall secretaries and security guards physically assaulted Sara York, a columnist for website 247, when she tried to photograph the municipal carnival event. York, a transgender woman who is visually impaired, was removed from the city hall even though she had authorisation to be there.

Women have been particularly targeted with physical and sexual assault. In Mexico, the police unlawfully detained and assaulted Enlace Noticias reporter Natalie Hoyos López and photojournalist Michelle Hoyos López after the two journalists covered a women’s rights event. They both reported that the police sexually assaulted them and released them only after they paid a fine.

In some countries, including Bolivia, Brazil, Haiti, Mexico and St Vincent and the Grenadines, assaults and gunshots are common. In Haiti, insecurity and violence continued to affect the daily lives of press workers, some of whom report facing attacks both from criminal gangs and Haitian security forces.

With multiple violent incidents including gunshots, death threats and attacks on journalists’ houses, Ecuador is experiencing an increasingly hostile environment towards the media. In December 2022, two people on a motorcycle fired gunshots at the home of Andrés Solórzano, owner of Radio Sono Onda in Portoviejo, Manabí province. He had received threats in the months before this attack. In March 2023, Ecuavisa journalist Lenin Artieda sustained injuries after a device exploded when he inserted USB drives containing threatening messages. These threatening letters were sent to five news outlets in Guayaquil and Quito. The escalating situation further escalated with the tragic assassination of journalist and presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio in an electoral campaign rally in August 2023.

During critical democratic moments, such as elections, both state and non-state forces often target journalists as a means of trying to dissuade them from investigating stories, restricting the capacity of independent media to report on elections, and as a result impinging on voters’ rights to access information. This was exemplified in Guatemala’s recent elections, where two journalists from a TV news programme faced gunfire threats while covering the campaign. Throughout the campaign period in Guatemala, at least 96 incidents were reported, most of them linked to restrictions on public information.

Unsettling pattern: killings of human rights defenders on the rise

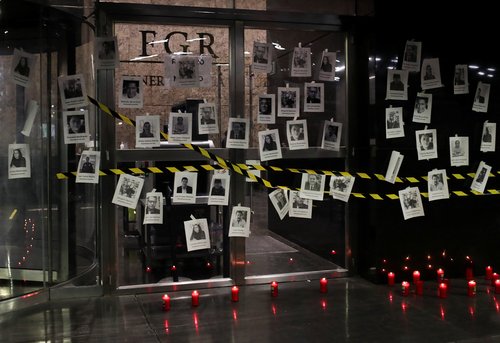

Human rights killings continue to be an issue of concern in the Americas, as HRDs work in a hostile environment marked by stigmatisation, threats, harassment and physical attacks. Although Colombia and Honduras represent the most extreme cases, they are not isolated examples. Since the previous report, the CIVICUS Monitor has also recorded cases of killings of HDRs in at least five other countries: Brazil, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, and Peru.

Indigenous, land and environmental defenders face severe risks as they bear the brunt of adverse impacts due to the exploitation of resources in their territories and a lack of effective legal protection while defending their rights. For instance, Colombia stands out as one of the deadliest countries for HRDs. The Department of Cauca is one of the most affected regions with more than 22 cases of killings registered from January to August 2023. Sixty-eight social activists and 14 signatories of the peace agreement were murdered in the first four months of 2023. Among those targeted were Indigenous leaders, LGBTQI+ activists, political campaigners and trade unionists.

Reported killings of HRDs can be linked directly to their gender and their fight to combat systemic discrimination. In Colombia, this is evident in cases such as lethal attacks targeting Lenis Yaneth Salazar Vera, a community council member, and Dania Sharith Polo, an LGBTQI+ HRD.

In Honduras, those working on issues related to land, the environment and agrarian conflicts remain at high risk of violence, particularly Indigenous peoples and Garífuna (Afro-descendant) communities. On 28 May 2023, Martín Morales, a land rights defender and member of Organización Fraternal Negra Hondureña (Honduran Black Fraternal Organisation) was found dead in the Gama River. His family had reported him missing the day before. It was the second time this year that a land rights defender from Triunfo de la Cruz community was found dead in the Gama River.

In Mexico, the targeted killings of mothers seeking their disappeared loved ones may be connected to factors including organised crime, extortion, human trafficking, kidnapping networks and corruption. This context underscores the complex and multifaceted nature of the challenges faced by those engaged in the pursuit of justice. An illustrative case occurred in November 2022, when HRD María Carmela Vázquez Ramírez was killed in Abasolo, Guanajuato. Vázquez was a member of Colectivo Personas Desaparecidas in Pénjamo (Collective of Missing Persons in Pénjamo) and was looking for her son, who disappeared in June 2022.

Guatemalan democracy under threat

During the 2023 general elections, the stability of Guatemala’s democracy faced constant and intense pressure. Ongoing and persistent legal proceedings, initiated in June 2023, to undermine the official results and suspend the winning Seed Movement party’s legal personality have raised concerns. Additionally, there are incidents of intimidation and criminalisation targeting electoral authorities and Seed Movement supporters. CSOs have also reported severe restrictions on the right to peaceful assembly for protesters demanding that the integrity of the electoral process be upheld.

A surge in attacks on HRDs, journalists and media workers has further compounded Guatemala’s current situation, encompassing intimidation, stigmatisation, criminalisation, arbitrary detention and defamation campaigns. Some of those cases exhibit a pattern of gender and racial discrimination.

Over the past three years, President Alejandro Giammattei’s administration and his allies have moved to reverse anti-corruption efforts and pursued abusive prosecutions, particularly against those reporting on abuse of power and corruption. In this context, substantial interference by political and economic elites, notably in the judiciary, amplifies the challenges.

In 2022, Guatemala significantly shifted its standing on the CIVICUS Monitor. It was first added to the CIVICUS Monitor Watchlist, which highlights countries experiencing significant declines in respect for civic freedoms, and then downgraded from an obstructed to repressed rating. This shift was prompted by a pronounced pattern involving the criminalisation of justice operators, HRDs and journalists, marking a distinct and troubling trend in the erosion of civic space through the institutionalisation of violence against civil society.

| COUNTRY | SCORES 2023 | 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 |

| ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA | 79 | ||||||

| ARGENTINA | 69 | ||||||

| BAHAMAS | 88 | ||||||

| BARBADOS | 95 | ||||||

| BELIZE | 73 | ||||||

| BOLIVIA | 52 | ||||||

| BRAZIL | 49 | ||||||

| CANADA | 81 | ||||||

| CHILE | 67 | ||||||

| COLOMBIA | 37 | ||||||

| COSTA RICA | 80 | ||||||

| CUBA | 14 | ||||||

| DOMINICA | 80 | ||||||

| DOMINICAN REPUBLIC | 73 | ||||||

| ECUADOR | 47 | ||||||

| EL SALVADOR | 46 | ||||||

| GRENADA | 82 | ||||||

| GUATEMALA | 39 | ||||||

| GUYANA | 75 | ||||||

| HAITI | 37 | ||||||

| HONDURAS | 36 | ||||||

| JAMAICA | 75 | ||||||

| MEXICO | 40 | ||||||

| NICARAGUA | 9 | ||||||

| PANAMA | 70 | ||||||

| PARAGUAY | 52 | ||||||

| PERU | 43 | ||||||

| SAINT LUCIA | 88 | ||||||

| ST KITTS AND NEVIS | 83 | ||||||

| ST VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES | 84 | ||||||

| SURINAME | 77 | ||||||

| TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO | 76 | ||||||

| UNITED STATES OF AMERICA | 65 | ||||||

| URUGUAY | 84 | ||||||

| VENEZUELA | 20 |