Americas

Rating Overview

Civil society in the Americas was fiercely tested in 2025, as the region is experiencing a widespread rollback of civic freedoms. Most people now live in obstructed civic space environments (around 60 per cent), while a further 30 per cent of the population is exposed to the worst conditions, closed or repressed civic space. Of 35 countries, civic space is rated as closed in three, repressed in seven, obstructed in six, narrowed in nine and open in 10.

Amid this decline, long-established democracies are showing signs of rapid authoritarian shift, marked by weakened rule of law and growing constraints on independent civil society. Argentina and the USA exemplified this trend.

The USA appeared twice on the CIVICUS Monitor Watchlist, which alerts to countries experiencing a rapid decline in civic freedoms, in 2025. It has now been downgraded from a narrowed to obstructed civic space rating following Donald Trump’s return to office in January 2025. Trump has issued unprecedented executive orders designed to unravel democratic institutions, global cooperation and international justice. Authorities have adopted a militarised response to large-scale protests triggered by aggressive and racist federal operations targeting migrant communities. Press freedom is under pressure, with censorship, judicial harassment and political interference manifesting in the cancellation or suspension of major talk shows, funding cuts affecting independent media and tighter restrictions on White House press access. Legislative and financial moves to rein in civil society have also gathered pace, with states pushing foreign-influence registration bills and officials floating contentious revisions to the Foreign Agents Registration Act that would make it easier to target and sideline independent civil society.

Repression of Palestine solidarity activism also intensified in 2025, with authorities cracking down on dissent across university campuses, including criminalisation of foreign-born students, disproportionate disciplinary measures against students and faculty, funding freezes and tax pressure on institutions and suspension of student groups, echoing a similar pattern of reprisals in 2024 during the Joe Biden administration. The government imposed sanctions on the International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecutor and judges, Palestinian organisations and Francesca Albanese, UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967.

Argentina’s rating has moved from narrowed to obstructed, as civic space has deteriorated sharply since President Javier Milei took office in December 2023. His administration has pursued aggressive restructuring of the state and economic austerity measures, reducing the capacity of the bodies responsible for guaranteeing fundamental rights. These reforms have triggered sustained mass mobilisations, with authorities responding by enforcing a 2023 ‘anti-picketing’ protocol and increasingly using arbitrary detentions and excessive force. In March 2025, police met a pensioners’ protest in Buenos Aires with one of the most brutal police operations of the past two years, resulting in around 700 injuries and at least 114 arbitrary detentions. Activists have also faced reprisals, including those defending Indigenous Mapuche territories amid wildfires in Patagonia in February 2025, and others opposing mining projects in Mendoza. Journalists report heightened levels of physical attacks, particularly in the context of protests, along with intimidation and public vilification, reflecting growing hostility from government officials.

El Salvador’s downgrade from obstructed to repressed comes after years of erosion of civic freedoms and the dismantling of institutional checks and balances. Since his first term in 2019, President Nayib Bukele has governed under an ongoing state of emergency that suspends constitutional guarantees and concentrates unparalleled power in the executive, now reinforced by constitutional changes enabling indefinite presidential re-election. In 2025, repression deepened steadily through the systematic targeting of activists and journalists, with alarming cases of criminalisation, including of prominent human rights lawyer Ruth López, and the adoption of a sweeping Foreign Agents Law imposing a 30 per cent tax on foreign funding and extreme sanctions, including administrative and criminal proceedings, cancellation and suspension of legal status or operating authorisation and fines of US$100,000 to US$250,000. The new restrictive legal framework, combined with a constrained environment for civil society, has seriously hindered CSOs’ operations and led major organisations to close their offices. Pressure on independent media soared, driving at least 53 journalists into exile by October 2025, as documented by the Association of Journalists of El Salvador.

Activists from countries rated as closed have increasingly become targets of attacks while in exile. The Group of Human Rights Experts on Nicaragua have documented transnational repression incidents against exiled Nicaraguans and their relatives, including killings, assaults, unlawful arrests and deportations and digital threats. The June 2025 killing of retired army major and outspoken government critic Roberto Samcam Ruiz in Costa Rica, after he reported death threats, shows how far the risks have grown. He had condemned military abuses since 2018 and was stripped of his nationality in 2023, joining at least 452 people deprived of their Nicaraguan nationality since February 2023.

Venezuelan authorities have employed different tactics, including systematically obstructing activists’ and journalists’ movement and human rights work by arbitrarily annulling or retaining passports. By May 2025, authorities had unlawfully revoked at least 40 people’s passports. Human rights organisations have raised alarm over the lack of protection for Venezuelan activists and opposition figures who fled after contested elections in 2024, driven out by political persecution. But exile has not kept them safe. In October 2025, Venezuelan HRD Yendri Velásquez and political consultant Luis Peche Arteaga were shot and injured by unknown assailants in Colombia. Both had left Venezuela due to the post-election crackdown. For now, there is no evidence linking the attack to the Venezuelan authorities, while investigations in Colombia remain stalled, a failure civil society has repeatedly criticised.

The assault on civic freedoms extends beyond the countries with the worst civic space restrictions: even in countries where civic freedoms are broadly protected, such as Canada, Chile, the Dominican Republic and Panama, there were incidents of excessive force during protests.

Civic Space Restrictions

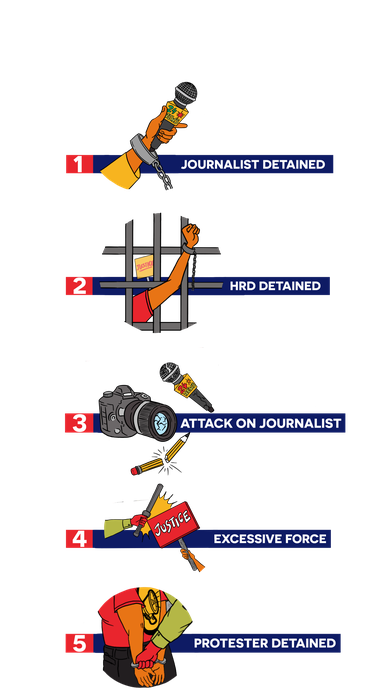

The most common violations of civic freedoms documented in the Americas in 2025 were, in order, attacks on journalists, intimidation of journalists, the detention of HRDs, the killing of HRDs and the use of excessive force during protests.

Journalists attacked, intimidated and threatened

Freedom of expression remained the most violated civic freedom in the Americas. Attacks, intimidation and threats against journalists continue to be among the region’s five most common violations since 2018, pointing to a steadily hostile climate for the media and rising dangers for journalists. This challenge is seen across all civic space ratings, from Canada’s open rating to Nicaragua’s closed status.

Attacks against journalists were documented in at least nine countries, intimidation in 14 and threats in 12. Protests are a particularly dangerous setting, accounting for 40 per cent of attacks against journalists recorded in the region. Security forces have frequently been identified as the main perpetrators of violence, raising concerns about excessive force.

In Argentina, the National Gendarmerie fired a teargas canister horizontally at photojournalist Pablo Grillo during pensioners’ protests near Congress in March 2025, striking him on the head and causing a severe brain injury that put him in intensive care. In Peru, police assaulted journalists covering the youth-led protests in Lima in September and October 2025, including firing projectiles, shoving them, striking them with teargas canisters, beating them with batons and hauling them out of protest zones.

Organised crime has made journalism a high-risk job in parts of the Americas. The situation has become particularly dire in Haiti. A deepening crisis, fuelled by spiralling gang violence, political deadlock and longstanding systemic injustices, has left journalists openly targeted. In April 2025, gang members in Mirebalais kidnapped journalist Roger Claudy Israël and his brother Marco, releasing a video threatening to execute them before freeing both after negotiations led by SOS Journalistes. In Petite-Rivière de l’Artibonite, gang members kidnapped journalist Valéry Pierre in December 2024, holding him for 45 days and beating, burning and torturing him before releasing him in January 2025.

In the most extreme cases, reporting on sensitive issues can be deadly. Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico and Peru remain among the most unsafe places for journalists, with Mexico still the deadliest place outside a warzone. The dangers were made brutally clear at the start of 2025. At least four journalists were killed in Mexico between January and March, including Raúl Irán Villarreal Belmont in Guanajuato and Calletano de Jesús Guerrero in the State of Mexico, both murdered by unidentified assailants after reporting on corruption and political issues. The continued killings show how state protection systems are failing, leaving journalists exposed and impunity entrenched.

Hostile authorities and non-state actors have carried out threats, mainly against investigative journalists, with around half of these attacks taking place online. In Uruguay, journalist Patricia Madrid received a string of threatening messages on Instagram allegedly sent by the brother of a mayor after she published an editorial on a corruption case involving him. Particularly when women are targeted, intimidation can involve misogynistic and racist language. In Brazil, TV anchor Luciana Barreto was subjected to racist social media comments in March 2025 after condemning discriminatory speech in sport. In June 2025, journalist Sílvia Tereza reported threats that included suggestions of sexual violence. In Colombia, journalist Diana Saray Giraldo faced a wave of online harassment in January 2025 after a senator accused her of ‘profiling’ and called her posts ‘dangerous’. The senator’s remarks triggered misogynistic attacks across social media.

A worrying trend is emerging in which laws meant to protect women from violence are being weaponised to silence the media. In Guatemala and Paraguay, authorities have used these protections to censor journalists, securing gag orders and no-contact rulings that block investigations and shut down reporting. For instance, in Paraguay, a woman senator from the ruling Colorado Party targeted journalist Laura Martino and two colleagues, filing complaints under Law 5,777/2016,on the Comprehensive Protection of Women Against All Forms of Violence. In December 2024, a court order banned them from making allegedly insulting or denigrating statements about the senator and barred any actions deemed to constitute harassment, intimidation or persecution on the basis of gender, under warning of judicial contempt.

Journalists were particularly at risk during elections. In Bolivia, during the August 2025 general election, at least 20 reporters were assaulted or harassed by unknown assailants, and at least one was followed and questioned by police throughout her election-day coverage. In Guyana, tensions arose during the September 2025 general election when President Irfaan Ali verbally attacked the Guyana Press Association as ‘biased’, ‘politically motivated’ and ‘undemocratic’ after it raised alarms about growing hostility toward the press. Election-season pressure took a different form in Canada: journalist Rachel Gilmore faced online harassment in March 2025 after a Conservative Party spokesperson publicly smeared her over a fact-checking segment, launching a wave of attacks that led the TV station to cut her slot.

Pressure from top officials on journalists has increased across the Caribbean. In the Bahamas, Prime Minister Phillip Brave Davis publicly lashed out at a reporter in July 2025 after she exposed inaccurate budget claims. In St Vincent and the Grenadines in February 2025, Prime Minister Ralph Gonsalves repeated unproven allegations that the media and opposition receive foreign funding recasting critical reporting as a threat to national sovereignty.

Human rights defenders detained

Detentions of HRDs has entered the region’s top five violations for the first time, with cases recorded in at least 12 countries, including Argentina, Dominica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Mexico and Paraguay. Authorities are increasingly abusing criminal law to label activists as criminals, enemies and terrorists, using public smears, vague charges and prolonged pretrial detention to silence them.

In countries with longstanding authoritarian governments, political tensions have been met with a sharp escalation in repression. Arbitrary detentions and enforced disappearances are being used as systemic tools to crush dissent, with activists arrested without warrants, held incommunicado and convicted without proper legal defence. In Nicaragua, a July 2025 police sweep led to the arrest of an entire family who were accused of conspiracy and treason in apparent retaliation for their opposition to the government. Shortly after, opposition politician Mauricio Alonso Petri was taken, disappeared and later found dead after 38 days in state custody. The crackdown surged after the anniversary of the Sandinista Revolution, with at least 33 people detained, including whole families and children, with authorities refusing to reveal their whereabouts or wellbeing.

In Venezuela, authorities are using incommunicado detention and vague national security charges to target prominent HRDs, including well-known activists from leading Venezuelan CSOs. On 7 January 2025, authorities arbitrarily detained Carlos Correa, director of the freedom of expression organisation Espacio Público. His whereabouts remained unknown for eight days, despite repeated requests for information from his family and legal representatives. Two days later, officials took him before an antiterrorism court without access to trusted legal counsel or the ability to communicate externally. Yet authorities continued to deny knowledge of his location, even as it rejected a habeas corpus petition filed on his behalf. Correa was released on 16 January 2025.

In May 2025, Eduardo Torres, a lawyer with the Venezuela Program Education-Action on Human Rights (PROVEA), was forcibly disappeared for 96 hours. His detention was only acknowledged following public pressure from civil society and a statement by UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk. The Attorney General linked him, without formal charges, to alleged conspiracy, criminal association, terrorism and treason in relation to parliamentary and regional elections. Between January and August 2025, at least 44 arbitrary detentions were documented by the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, evidence of a wider pattern of repression and the systematic criminalisation of independent civil society in the aftermath of the 2024 election crisis.

Authorities continue to target democracy activists in Cuba. Independent writer and journalist José Gabriel Barrenechea was arbitrarily detained in November 2024 on public disorder charges linked to protests. His detention has been marked by serious due process violations, denial of family contact and a dramatic deterioration in his health while in prison. De facto house arrests also remain a common tactic of suppressing dissent.

In the USA, Palestine solidarity activism has come under intense pressure. Following campus protests in 2024, authorities escalated their response, and from early 2025 began using immigration enforcement to silence dissent. Federal authorities have arbitrarily detained foreign-born students despite having no evidence of criminal activity, revoking visas and stripping away due-process protections using archaic and obscure clauses of the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act, which allows deportation on grounds of ‘potentially serious adverse foreign policy consequences’.

One emblematic case is that of Mahmoud Khalil’s arbitrary detention. ICE agents, without documentation, informed him his visa and residency had been revoked. He was transferred 1,600 kilometres away from his home to the Central Louisiana ICE Processing Centre, a facility long criticised for abusive conditions and inadequate medical care by human rights organisations, without any notice to his family or legal representatives. Similar actions targeted doctoral student Rümeysa Öztürk and postdoctoral fellow Badar Khan Suri in March 2025, and undergraduate Mohsen Mahdawi in April 2025. These form part of a broader crackdown in which student activists are doxxed, interrogated, suspended and subjected to surveillance simply for speaking out.

In Guatemala, HRDs continue to face relentless persecution as the Prosecutor’s Office and allied judges deepen practices that criminalise civil society, particularly Indigenous movements, the backbone of resistance to corruption and impunity. In April 2025, authorities arbitrarily detained Héctor Chaclán and Luis Pacheco, former Indigenous authorities of the 48 Cantons of Totonicapán, on obstruction of justice and terrorism charges for their role in peaceful October 2023 mobilisations defending the general election victory of President Bernardo Arévalo. Despite early efforts by the Arévalo administration to open dialogue with civil society, progress remains limited. Meanwhile, emblematic cases, such as the continuing criminalisation of former anti-corruption prosecutor Virginia Laparra and the three-year arbitrary detention of journalist José Rubén Zamora, show that politically motivated prosecutions persist.

Human rights defenders killed

In 2025, the Americas remained the world’s deadliest region for HRDs, with killings documented in at least nine countries, including Brazil, Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico and Peru, which are among the most dangerous. Many of those murdered were environmental and land defenders resisting extractive industry projects. Others were killed for promoting democratic freedoms, LGBTQI+ rights and social justice.

Colombia is at the epicentre of this crisis, as Global Witness has repeatedly warned. The Institute for Development and Peace Studies recorded close to 200 killings between January and October 2025, most carried out with total impunity. The killings are concentrated in regions already experiencing acute violence, including Antioquia, Cauca, Nariño, Norte de Santander and Valle del Cauca, where Afro-Colombian, campesino and Indigenous communities bear the brunt of armed conflict.

For example, in June 2025, Indigenous Awá defender Aurelio Araujo Hernández, coordinator of the Awá Indigenous people’s traditional authority in Ricaurte Camawari, was assassinated alongside his two protection officers. The attack followed months of threats, the burning of his home and growing pressure from armed groups attempting to infiltrate Awá governance structures. Four Awá leaders had been killed by mid-2025, despite longstanding precautionary measures.

In Honduras, environmental defender Juan Bautista Silva and his son, Juan Antonio, were murdered after gathering evidence of illegal logging with the aim of supporting a complaint to prosecutors. Their bodies were found at the bottom of a cliff, showing signs of extreme violence. Shortly before he and his son disappeared, Silva received a call from an unknown number, allegedly impersonating an official. Silva had spent decades defending community forests and had survived a 2020 attack, yet his repeated complaints were ignored.

Year after year, the recurrence of this shameful trend reveals an urgent regional need for far stronger protections for HRDs. The Escazú Agreement remains under-enforced as more needs to be done to translate its commitments into practical national action plans.

Countries of concern: Ecuador and Peru

Civic space conditions are rapidly deteriorating in Ecuador. President Noboa is advancing sweeping laws that threaten CSOs. Security forces used excessive and lethal force against Indigenous-led peaceful protests in September and October 2025. The crackdown resulted in the killing of two Indigenous leaders, hundreds of injuries and over 200 detentions, amid reports of enforced disappearances. The government’s recurrent imposition of states of emergency has further restricted freedoms of association, movement and peaceful assembly, disproportionately affecting Afro-Ecuadorian and Indigenous communities. Attacks on journalists have escalated, including killings, threats and forced exile, extending the pattern that saw Ecuador placed on the CIVICUS Monitor Watchlist in 2023.

Peru is another country of concern as civic space declines amid renewed political turmoil following the removal of President Dina Boluarte and appointment of interim president José Jeri in October 2025. Security forces have met youth-led protests with lethal force, and in late October, a state of emergency was declared in Callao and Lima, leaving key constitutional guarantees suspended and heightening the risk of arbitrary detentions and abuses by security forces. Congress has advanced legislation that falls far short of international human rights standards, including amendments to the Peruvian Agency for International Cooperation law that expand the agency’s oversight powers and classify any unapproved activity or use of funds as a serious infraction, and a new law approved in August 2025 that grants broad amnesties for security forces implicated in serious human rights violations. Combined with ongoing violence against HRDs and journalists, these developments are driving a heavily constrained civic space. In 2024, Peru’s civic space rating was downgraded from obstructed to repressed, reflecting years of cumulative and systematic erosion of civic freedoms.

| COUNTRY | SCORES 2025 | 2024 | 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 |

| ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA | 71 | |||||||

| ARGENTINA | 59 | |||||||

| BAHAMAS | 88 | |||||||

| BARBADOS | 90 | |||||||

| BELIZE | 79 | |||||||

| BOLIVIA | 50 | |||||||

| BRAZIL | 55 | |||||||

| CANADA | 82 | |||||||

| CHILE | 76 | |||||||

| COLOMBIA | 38 | |||||||

| COSTA RICA | 78 | |||||||

| CUBA | 13 | |||||||

| DOMINICA | 70 | |||||||

| DOMINICAN REPUBLIC | 74 | |||||||

| ECUADOR | 47 | |||||||

| EL SALVADOR | 35 | |||||||

| GRENADA | 89 | |||||||

| GUATEMALA | 40 | |||||||

| GUYANA | 71 | |||||||

| HAITI | 34 | |||||||

| HONDURAS | 38 | |||||||

| JAMAICA | 84 | |||||||

| MEXICO | 40 | |||||||

| NICARAGUA | 5 | |||||||

| PANAMA | 73 | |||||||

| PARAGUAY | 52 | |||||||

| PERU | 40 | |||||||

| SAINT LUCIA | 88 | |||||||

| ST KITTS AND NEVIS | 90 | |||||||

| ST VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES | 90 | |||||||

| SURINAME | 77 | |||||||

| TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO | 84 | |||||||

| UNITED STATES OF AMERICA | 56 | |||||||

| URUGUAY | 84 | |||||||

| VENEZUELA | 14 |