Americas

Rating Overview

The past year in the Americas showed that significant civic space changes can be incremental, just as they can be precipitous and abrupt. In most cases, it is not a radical transformation that drives civic space to improve or worsen but a combination of practices, regulations and policies. Structural change, such as the adoption of a new constitution, is rare. Instead, fundamental rights to freedoms of association, peaceful assembly and expression are often preserved and protected through specific court decisions, progressive adoption of enabling regulation, efforts by political leaders to recognise the importance of civil society and dozens of other developments.

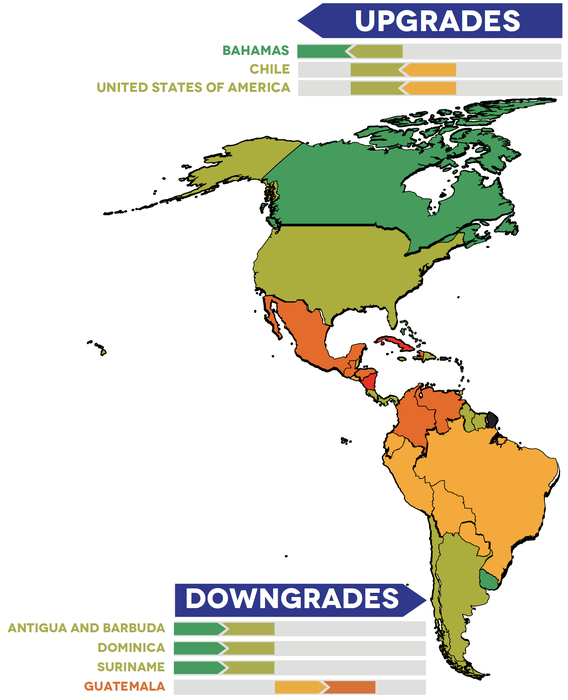

This is illustrated by some of the rating changes seen this year. Chile and the USA move from the obstructed to the narrowed category. Both countries were downgraded in 2020 following the violent repression of mass protest movements and have seen leadership changes since then. In both cases improvements have not come about in a straight line but amid setbacks. Meanwhile, Guatemala is downgraded from obstructed to repressed, following years of gradual erosion of democratic institutions and reduction of the space for civil society and the press.

Of 35 countries in the region, there are now eight where civic space is considered open. Thirteen countries are rated as narrowed, six as obstructed and another six as repressed. In two countries civic space remains closed, the only category that saw no regional changes compared to 2021. In addition to the rating changes mentioned above, the Bahamas was moved from narrowed to open while Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica and Suriname moved to narrowed.*

In Chile, the path toward a new constitution was extended after voters rejected the proposal from a Constitutional Assembly convened on the heels of the 2019 social uprising. The south of the country saw continued unrest and militarisation, with the government of President Gabriel Boric failing to make progress in resolving the longstanding conflict with Indigenous Mapuche people.

However, the new government changed course in relation to the social uprising, withdrawing some prosecutions of protesters and taking steps to provide reparations and access to justice for victims of repression. President Boric also signed and championed the ratification of the Escazú Agreement, a binding environmental treaty that includes provisions to improve the situation of HRDs. While much more could be done to ensure durable changes, these advances have put Chile on a more positive trajectory, recognised in its rating upgrade.

A similar scenario is seen in the USA, where the Biden administration has sought to improve on Trump’s relationship with the media and stressed the importance of democratic institutions. The government took steps to safeguard fundamental freedoms and civil society, with policies to strengthen police accountability, support workplace organising and protect humanitarian assistance worldwide. Yet while civic space in the USA has improved enough to drive a change of rating, trends that negatively affected the space for civil society and the media endure. The year saw lawmakers adopting further restrictions on protests and a slew of state-level bills limiting free speech in schools. Incidents of excessive force and arbitrary arrests of protesters remain recurrent, and those charged are subject to increasingly harsh penalties. The authorities also continue to criminalise whistleblowers.

Conversely, in Guatemala, there was a much clearer trend in the deterioration of civic space as the government moved to undermine the rule of law and reverse the anti-corruption efforts of recent years. The authorities have gradually chipped away at judicial independence and adopted restrictive legislation. Over the past three years, the government of President Alejandro Giammattei has systematically pursued abusive prosecutions of peace and justice advocates, judicial officials and journalists, in an effort to silence critics and those who have sought to tackle political corruption. HRDs have faced increasing attacks, while the institutional spaces for monitoring their situation and ensuring their protection have been weakened. Increasing authoritarianism is particularly concerning in light of the country’s general elections in June 2023, which could lead to a consolidation of this reduced civic space.

*For Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Dominica and Suriname – the CIVICUS Monitor added more indicators this year compared to 2021. Therefore rating changes were

prompted by additional information rather than a change in the situation on the ground.

Civic Space Restrictions

In line with the global trend, there has been a sharp increase in cases of harassment in the Americas over the past year, making this the top violation recorded across the region. Attacks on journalists, the detention of protesters, intimidation and protest disruptions were also frequent. Women, Indigenous and environmental defenders were commonly involved in civic space incidents, often coming under fire from state and non-state actors.

Harassment

Across the region, hostile authorities and non-state actors have carried out repeated attacks and threatening actions to terrorise HRDs and journalists. These behaviours put pressure on HRDs and journalists to stop their activities, often by causing them emotional and mental distress. Harassment can lead to self-censorship and, in extreme cases, push those targeted into displacement or exile. In 2022, these cases were documented in at least 18 countries in the region. Their occurrence was widespread, featuring in 44 per cent of all CIVICUS Monitor reports on the Americas over the year.

Harassment can unfold in multiple forms, from repeated police citations to house break-ins, menacing phone calls and online smear campaigns. Often HRDs and journalists who are subjected to harassment experience more than one type of threatening behaviour, including physical attacks. In many cases, those carting out the harassment are empowered by impunity for their actions. Faced with an escalation of hostility against the Cabécar people in Costa Rica, Indigenous land defender Doris Ríos said, ‘What is frustrating is that you file complaints and nothing is done’. Ríos’s comment followed an attack on her territory that left 13 people injured in February 2022. Two months later, her son was threatened at knifepoint just days after she publicly warned about the repeated death threats she and her family had received from local ranchers.

In Venezuela, a human rights lawyer moved her family out of the country after being faced with recurrent threats and surveillance for cooperating with UN human rights mechanisms. In El Salvador, HRDs and journalists were exposed to online harassment, often championed by the authorities, who used their social media accounts to stigmatise them. This behaviour by leaders, which has worsened under the current government’s exceptional measures against gang violence, encouraged waves of attacks, insults and threats from supporters. In some cases, outspoken government critics have also been hacked, subjected to surveillance and have had their privacy exposed online.

In Nicaragua, harassment was part of a complementary toolbox of tactics adopted by the authorities to silence civil society voices. Leaders and members of CSOs were personally targeted with harassment and criminalisation, and alongside this, thousands of organisations had their legal status cancelled using arbitrary procedures, forcing many to shut down their operations. Some groups had their offices and equipment seized.

Particularly when women are targeted, harassment can involve threats of sexual violence and sexist language. A journalist in Bolivia received anonymous rape and death threats over her reporting on femicides. The messages against her seemed to indicate that she may have been stalked for some time, which led the country’s Ombudsperson’s Office to call on security forces to provide her with urgent protection measures.

Attacks on journalists

Throughout 2022, physical attacks on journalists and media outlets took place in at least 17 countries of the Americas. It is the fifth year in a row that this violation has appeared among the top three for the region, displaying the persistence of a hostile environment for the media and the great personal risks journalists can face for doing their crucial work.

The CIVICUS Monitor documented cases of journalists being shot at by unidentified assailants and assaulted by police and protesters while covering demonstrations, and being attacked by politicians and their supporters, along with many other violent incidents. Offices of media outlets were attacked with explosives, firearms and arson attacks in several countries, including Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico and Peru.

Perpetrators remained unknown in many of the attacks, but in some cases those responsible were identified but not sanctioned. In Guatemala, a journalist was beaten and detained and had his equipment damaged by police officers when covering the repression of a protest. Investigators shelved his complaint against the officers who assaulted him. Meanwhile, charges against him, initially dismissed by a local court, were reinstated at the request of public prosecutors.

In extreme cases, violence resulted in killings, with 2022 becoming one of the region's most deadly years on record for press workers. The CIVICUS Monitor documented such cases in nine countries in the Americas. In Chile, Francisca Sandoval became the first journalist to be killed in the line of duty since the Pinochet dictatorship ended in 1990. Shooters opened fire on Workers’ Day protesters in Santiago, hitting her and two other journalists. In Honduras, Indigenous communicator Pablo Isabel Hernández Rivera was shot and killed. He had previously been subjected to threats and a smear campaign. The community radio station where he worked had also been sabotaged and threatened with closure.

In Mexico, the violence grew so extreme that journalists held multiple protests demanding justice for murdered colleagues and urgent measures to protect the safety of press workers. Haitian journalists also faced a spiral of violence while attempting to cover the country’s multidimensional crisis. They became targets of criminal gangs, with cases of kidnapping, drive-by shootings and ambushes, and have also been victims of police brutality in protests.

Detention of protesters

Across the region, the rising cost of living drove masses to the streets to demand living wages and public policies to contain price surges and support those living in poverty. Protesting remained an important tactic for people to call for change, from those protesting against environmentally damaging projects to women urging action against gender-based violence. However, security forces repeatedly resorted to detentions to disrupt protests. The CIVICUS Monitor recorded protests in at least 23 countries of the Americas, and in 13 of those, there were instances of detention of protesters. Detentions were documented in 40 per cent of all reports on protests in the region throughout 2022.

Protest-related detentions occurred in countries in every rating category, from places where civic space is generally protected to those where it is most constrained. In Canada, peaceful protests by climate and environmental activists were often disrupted with detentions and police said they planned to pursue charges against those staging disobedience actions and blocking roads. Similar instances where seen in the USA and Argentina, where the frequent repression of protests against the construction of a highway led a court in Córdoba to issue a preventive habeas corpus for those arrested for protesting.

The cost of living crisis led thousands to protest in Panama, in the largest demonstrations seen in the country in recent years. After three weeks of protests, the police disclosed they had arrested 102 people, 80 of whom had hearings for obstruction of transit and disrupting peaceful coexistence. There were also multiple reports of protesters being dispersed by police using teargas and pellets. In Venezuela, unions held multiple protests against hyperinflation and the loss of purchasing power, calling for living wages. In some cases, protesters were detained and prevented from marching.

In Cuba, relatives of detained protesters and feminist advocates who were supporting them were arrested for protesting near a court. One of the activists detained later said she continued to face harassment and surveillance for her advocacy work.

Ecuadorian Indigenous peoples and other movements striking against the government’s social and economic policies were met with a crackdown in June 2022. In just 18 days, the civil society coalition Alianza DDHH registered 127 cases of human rights violations, including nine deaths, 318 people injured and at least 199 protesters detained. Among those arbitrarily arrested was Leonidas Iza, leader of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador, who was accused by the authorities of paralysing public services. At the end of September, charges against him were thrown out in court.

In the line of fire

Violence against HRDs and journalists remains acute in the Americas. The region accounted for a disproportionate number of killings of HRDs recorded by the CIVICUS Monitor, with over 60 per cent of the total cases documented in 2022. Similarly, it was the region with the highest number of reports of killings of journalists. HRDs were killed in at least eight countries and journalists in at least nine.

Indigenous, environmental and land rights defenders were disproportionately affected by this violence. In Brazil, Indigenous advocate Bruno Pereira and British journalist Dom Phillips were ambushed and killed as they returned from a reporting trip in a remote part of the Amazon rainforest. They had been documenting Indigenous people’s efforts to resist predatory criminal activities in their territory. The 10-day search for them was driven initially by Indigenous organisations in the face of government negligence, something symptomatic of the attitude of the government of former President Jair Bolsonaro toward human rights, Indigenous peoples and independent media.

Sadly, Colombia saw a new record number of assassinations of HRDs and social leaders. According to the country’s Ombudsperson’s Office, nearly 200 of these advocates were killed in 2022. Frontline defenders and community leaders were particularly targeted. In Honduras, a trans activist who advocated for the rights of people with HIV was killed in a brazen attack in her home. Before she died, Thalía Rodríguez had underscored in an interview that she was one of the last Honduran trans activists of her generation still living.

In Mexico, at least five women defenders who searched for answers about missing people were killed. Press workers faced a particularly deadly year in the country, with four journalists assassinated in January 2022 alone. The authorities have failed to coordinate a comprehensive response to the violence. Mexico’s underfunded and understaffed protection mechanism lacks the capacity to ensure the safety of the hundreds who need it. 2022 ended with Mexico again topping the list of countries outside war zones with the most journalists killed during the year.

The reproduction of this shameful trend, year after year, displays the urgent need for governments across the region to adopt and improve measures to protect HRDs and journalists and to tackle the prevailing impunity for crimes committed against them.

Country of concern: Peru

At the end of 2022, Peru was launched into a new chapter of its long-lasting institutional crisis when former President Pedro Castillo was removed by Congress on 7 December 2022, directly after his attempt to dissolve the legislature. The move followed months of political instability, with the opposition-controlled Congress often at odds with Castillo during his 15 months in office. The rapid turn of events that brought former Vice-President Dina Boluarte to power sparked protests by Castillo supporters, who saw his removal and arrest as a coup by political elites.

Protests, particularly those in rural areas and led by Indigenous and campesino people, were met with excessive force by law enforcement agencies. Between 8 December 2022 and 27 January 2023, at least 57 people died, including six minors, and over 1,500 were injured. The majority of the deaths were alleged extrajudicial killings perpetrated by law enforcement officers. Civil society has recorded numerous other human rights violations, including arbitrary arrests, excessive use of force, sexual violence and attacks on journalists. President Boluarte and other officials have failed to condemn abuses by police and armed forces and sometimes blamed protesters for ‘causing chaos’ and stigmatised them. Amid the turmoil, human rights organisations have been targeted and harassed by radicalised far-right groups.

The violent police response to these protests is shocking but not unprecedented. Just months earlier, a strike led by transport workers against rising fuel, fertiliser and food costs was also met with detentions and excessive force. In recent years, security forces have repeatedly used disproportionate force in response to protests, particularly those led by excluded populations away from the major cities. Rather than pursuing reforms to address police violence, in recent years Peruvian authorities have adopted a law shielding officers from prosecution for abuses.

| COUNTRY | SCORES 2022 | RATING 2022 | RATING 2021 | RATING 2020 | RATING 2019 | RATING 2018 |

| ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA | 79 | |||||

| ARGENTINA | 69 | |||||

| BAHAMAS | 92 | |||||

| BARBADOS | 82 | |||||

| BELIZE | 73 | |||||

| BOLIVIA | 44 | |||||

| BRAZIL | 47 | |||||

| CANADA | 84 | |||||

| CHILE | 66 | |||||

| COLOMBIA | 33 | |||||

| COSTA RICA | 71 | |||||

| CUBA | 17 | |||||

| DOMINICA | 79 | |||||

| DOMINICAN REPUBLIC | 78 | |||||

| ECUADOR | 57 | |||||

| EL SALVADOR | 47 | |||||

| GRENADA | 86 | |||||

| GUATEMALA | 40 | |||||

| GUYANA | 76 | |||||

| HAITI | 40 | |||||

| HONDURAS | 37 | |||||

| JAMAICA | 80 | |||||

| MEXICO | 38 | |||||

| NICARAGUA | 15 | |||||

| PANAMA | 67 | |||||

| PARAGUAY | 51 | |||||

| PERU | 51 | |||||

| SAINT LUCIA | 86 | |||||

| ST KITTS AND NEVIS | 84 | |||||

| ST VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES | 85 | |||||

| SURINAME | 79 | |||||

| TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO | 73 | |||||

| UNITED STATES OF AMERICA | 70 | |||||

| URUGUAY | 81 | |||||

| VENEZUELA | 23 |