Tactics of Repression

Of all the civic space violations recorded on the CIVICUS Monitor, close to 44.8 per cent, over 1,350 civic space incidents, related to freedom of expression. Over 900 violations, 29 per cent of total violations, were recorded in the area of freedom of peaceful assembly, while violations of freedom of association constituted 26.6 per cent, with more than 800 incidents recorded.

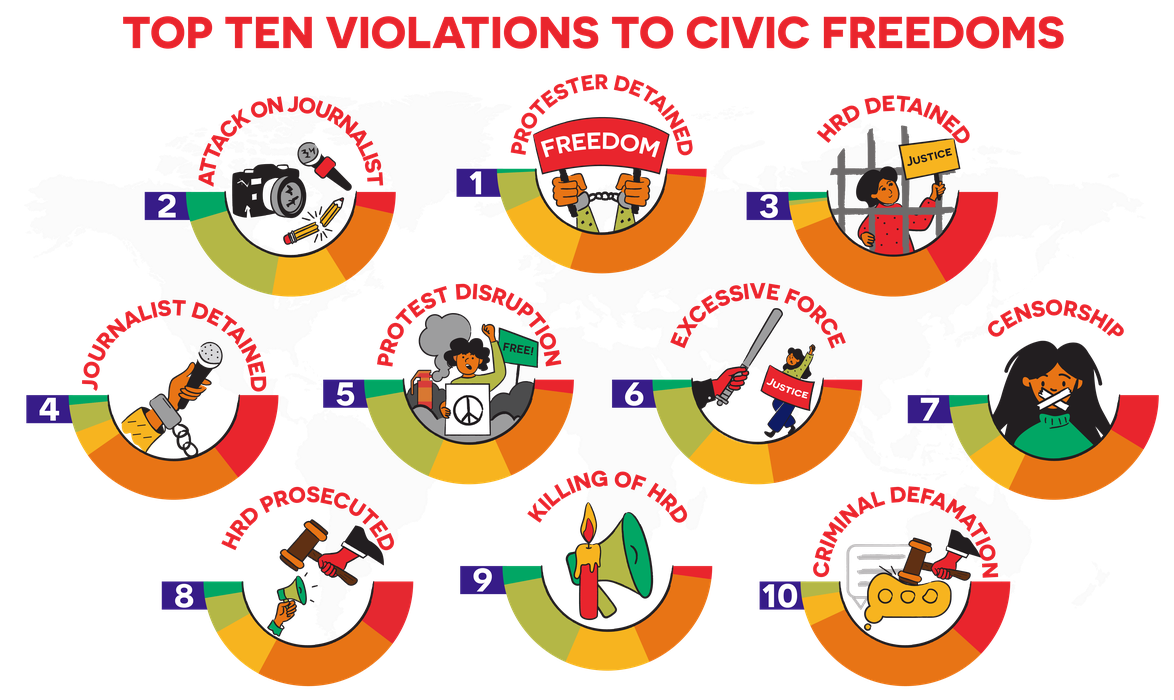

The top global civic space violations are the detention of protesters, documented in at least 82 countries, followed by the detention of journalists, reported in at least 73, and the detention of human rights defenders (HRDs), documented in at least 71.

This year, civic space violations related to Israel and the Occupied Palestine Territories (see Middle East and North Africa (MENA) section) and the expression of solidarity with Palestinian people continued to be a concerning trend, with the latter particularly taking place in the global north.

Protest rights under attack

In 2025, people took to the streets in countries around the world to demand action and denounce government inaction on issues including the climate crisis, corruption, electoral fraud and irregularities, the high cost of living and poor basic services. And around the world, governments reacted by detaining protesters, a repressive tactic documented in over 200 protests in at least 82 countries. Other tactics included protest disruption, documented in at least 70 countries, and the use of excessive force against protesters, in at least 67.

Climate change protests and protests showing solidarity with Palestinian people continued to be targeted with repression, including detentions, prosecution, protest bans and the introduction of restrictive laws limiting peaceful assembly (see Restrictive Laws), particularly in Europe, North America and Australia.

In Ireland in March 2025, police forcibly removed protesters from the Mothers against Genocide group from the gates of the parliament buildings and detained 11 under the Criminal Justice (Public Order) Act of 1994. They were later released with formal warnings. In the UK, police arrested hundreds in July 2025 during Defend our Juries protests to oppose the government’s plan to proscribe direct action group Palestine Action as a terrorist organisation, with police targeting peaceful protesters simply for holding placards reading ‘I support Palestine Action’. In March 2025, police in New York, USA, arrested around 100 protesters at a non-violent sit-in at Trump Tower to demand the immediate release of activist Mahmoud Khalil, a permanent US resident arbitrarily detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents in March 2025, and to protest against the Trump administration’s stance on Palestine-related activism.

In the Netherlands, police arrested over 700 Extinction Rebellion (XR) activists on 11 January 2025 after the climate action group blocked a motorway near The Hague to demand an end to fossil fuel subsidies. Municipal authorities banned the protest and police used water cannon in freezing weather. On 28 January 2025, the Dutch parliament adopted a motion labelling XR as an ‘unlawful, society-disrupting and vandalistic organisation’ that does not serve the public interest and urged the government to revoke XR’s public benefit status. In Australia, police charged 170 people, including 14 children, in November 2024 for attending a climate protest in the Port of Newcastle organised by the activism group Rising Tide.

The use of detentions as a tactic to shut down environmental protests was also documented in several countries. In Peru, authorities arbitrarily detained five farmers during a protest against the El Algarrobo mining project in Tambogrande, a rural district in the region of Piura.

The protest, organised by local farmers, community leaders and the Frente de Defensa Urbank de Tambogrande, a local organisation defending land and water, sought to defend agricultural livelihoods and water sources in a region dependent on fruit production and small-scale farming.

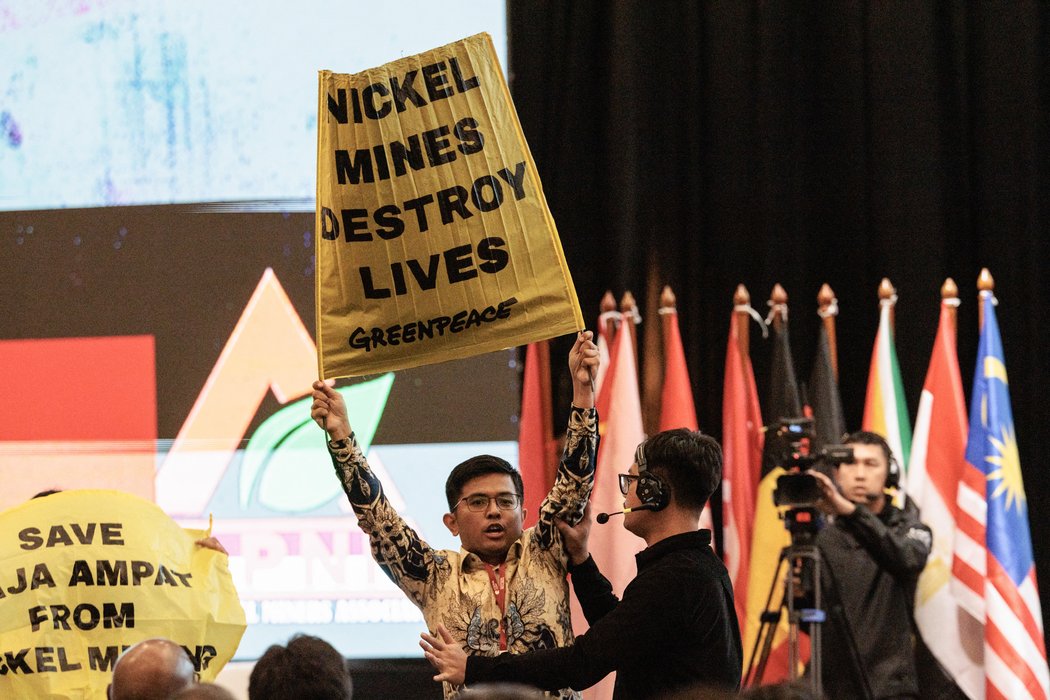

On 3 June 2025, three Greenpeace Indonesia activists and a young Papuan woman were arrested after they unfurled banners and made speeches about the environmental damage caused by extractive industries at the Indonesia Critical Minerals Conference and Expo in Jakarta. In Uganda, authorities arrested 11 environmental activists during a protest in February 2025 against the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP), charging them with ‘common nuisance’. The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights condemned Uganda’s escalating repression of environmental HRDs in its 81st Ordinary Session held in October and November 2024. In Tunisia, police violently arrested Mohamed Ali Ritmi, an activist and member of the Association tunisienne pour la justice et l’égalité, on 23 May 2025 during a peaceful protest organised by the Stop Pollution movement in the Gabès region.

2025 saw several mass mobilisations across the world, frequently led by young people, over corruption, the high cost of living, poor basic services and other governance failures. Generation Z-led protests – sustained mass anti-government mobilisations driven by young protesters sharing common protest symbols – took place in several countries including Madagascar, Morocco, Nepal and Peru. States responded to protests with killings, excessive force and detentions. At least three people were killed and at least 400 arrested during Morocco’s ‘Gen Z 212’ protests that erupted in September 2025 in several cities. Security forces were accused of using excessive force, including live ammunition, rubber bullets and teargas, in response to largely peaceful protests. Security forces killed and detained young protesters at other Gen Z-led protests, including in Madagascar and Nepal. In Kenya, over 1,500 people were arrested and 65 people killed between 25 June and 11 July 2025 in protests to mark the anniversary of the 2024 Gen Z-led protests against tax hikes that grew into a movement against systemic corruption, poor governance and police brutality, and which was met with a violent crackdown. Other serious violations, including cases of rape and gang rape by suspected state-sponsored personnel, were reported.

Authorities also detained people in response to election-related protests, including mobilisations against electoral fraud, the exclusion of political opposition and the lack of credible, transparent elections. Police arrested over 4,200 people in largely peaceful protests that erupted in the aftermath of October 2024 general elections in Mozambique that were marred by widespread irregularities. As violence flared, local civil society group Plataforma Decide reported hundreds of killings between 21 October 2024 and 16 January 2025.

In Côte d’Ivoire, ahead of the 25 October 2025 presidential election, police arrested around 700 people in protests against the Constitutional Council’s exclusion of leading opposition candidates. Dozens were sentenced to three years in prison for disturbance of public order, participation in a prohibited march and unlawful assembly. Meetings and gatherings of excluded opposition candidates were banned.

In Turkey, police arrested or detained close to 2,000 people in a crackdown on protests in March 2025 following the arrest of Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, a key opposition figure who is widely seen as President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s main challenger in the 2028 presidential election.

In Bolivia, four consecutive days of protests erupted in La Paz in May 2025 after the electoral authority blocked former president Evo Morales’s registration for the 2025 general election. Police prevented protesters reaching the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, leading to violent clashes, 20 detentions and several injuries. The protests reflected a struggle between Morales and former President Luis Arce, former allies competing for control of the ruling party. Authorities also detained people for taking part in protests to criticise government actions, laws and policies. Pension reforms sparked protests in Argentina, with over 100 people arrested in March 2025, including journalists, older people, passers-by unaware of the demonstration, students, workers and two schoolchildren.

In Indonesia, police arrested at least 161 people in the student-led Indonesia Gelap – Dark Indonesia – protests that erupted in March 2025 after the adoption of revisions to the National Armed Forces (Tentara Nasional Indonesia) Act to expand the military’s role in civilian governance. In Iran and Saudi Arabia, authorities have systematically used the death penalty to target protesters, with at least two executed in Saudi Arabia, while women HRDs (WHRDs) in Iran face imminent execution after receiving the death penalty for protesting for women’s rights.

Journalists detained

In numerous countries, authorities are targeting freedom of expression and use a range of tactics to silence critical voices and deter journalists from holding authorities to account or reporting on issues considered sensitive. Repressive tactics include attacks, detention, intimidation and threats against journalists. The arrest and detention of journalists, the second-highest civic space violation and documented in at least 73 countries, is used as a means to prevent journalists reporting on corruption, democracy and human rights issues. Attacks on journalists, the fourth most prevalent civic space violation in 2025, were documented in at least 54 countries.

Over half of documented detentions of journalists in 2025 occurred in Africa South of the Sahara (see Africa chapter). Detention of journalists is also one of MENA’s top three civic space violations.

In 2025, authorities used a range of restrictive laws and provisions to detain journalists for their reporting, including cybersecurity laws, counterterrorism laws and false information laws, among other laws and restrictive provisions. On 17 March 2025, authorities in Mongolia detained eight journalists from Noorog Creative Studio for ‘undermining national unity’ under the Criminal Law Act, a charge that carries a prison sentence up to 12 years. The media outlet planned to release a documentary exploring Mongolia’s democratic processes from a citizen perspective. The eight were released after hours of interrogation and the confiscation of computers and hard drives.

In Benin, authorities regularly arrest and prosecute journalists for ‘harassment by electronic means’ under the 2018 Digital Code. On 15 July 2025, Cosme Hounsa, editor-in-chief of La Boussole newspaper, was arrested following a complaint by a government minister, Rachidi Gbadamassi, in relation to the outlet’s report on a legal dispute between Gbadamassi and another minister. Hounsa was released on summons pending further judicial proceedings.

In Turkey, authorities use counterterrorism laws to target activists and journalists. In January 2025, it was reported that three journalists, T24 editor-in-chief Doğan Akın, Gerçek Gündem editor-in-chief Seyhan Avşar and T24 managing editor Candan Yıldız, are facing eight years of prison on charges of ‘spreading misleading information’ and ‘making terrorist propaganda’ for their coverage of the killing of two Kurdish reporters in a suspected Turkish drone strike in Syria.

Defamation, insults and sedition remain criminal offences in many countries, enabling authorities to subject journalists to judicial harassment. On 23 November 2024 in Papua New Guinea, journalist and gender activist Hennah Joku was detained and charged under the Cybercrime Act, following defamation complaints by her former partner Robert Agen. Joku, a survivor of a 2018 assault by Agen, has documented her six-year journey through the country’s justice system, which resulted in Agen’s conviction. Joku was released after posting bail. On 1 July 2025, Faith Zaba, journalist and editor of the Zimbabwe Independent, was arrested and charged with ‘undermining the authorities or insulting the president’ after the publication of a satirical article that described the country as a ‘mafia state’ and mocked President Emmerson Mnangagwa and his leadership, particularly in his role as chair of the Southern African Development Community.

Investigative journalists, journalists working for independent media and journalists covering corruption are particularly vulnerable to arbitrary arrests. In Vietnam, where media are closely controlled by the communist one-party state, authorities frequently jail bloggers and independent journalists. On 7 October 2025, police arrested independent journalist Huynh Ngoc Tuan, who regularly posts commentary on human rights and politics on his Facebook page. He was charged with ‘propagandising against the state’ under the Penal Code, which carries a prison sentence of up to 20 years. On 8 April 2025, authorities in Caracas, Venezuela arbitrarily detained journalists Gianni González Nakary and Mena Ramos after a report on rising crime rates for the independent media outlet Impacto Venezuela. A few days later, a criminal court ordered the pretrial detention of both on charges of ‘hate crimes’ and ‘publishing false news’.

In Nigeria on 26 November 2024, soldiers detained Fisayo Soyombo, an investigative journalist and founder of the Foundation for Investigative Journalism, in Port Harcourt. The move was believed to be in connection with his investigative work uncovering corruption and smuggling activities facilitated by the Nigerian Customs Service. Soyombo was released after being held for three days. In Egypt, Zat Masr broadcaster and writer Ahmed Serag was detained in January 2025 on allegations of spreading false news and terrorism, in relation to an interview he conducted with Nada Mougheeth, wife of detained cartoonist Ashraf Omar. In February 2025, his detention was renewed for 15 days pending investigations.

In 2025, journalists were also frequently detained while covering protests. In Belgium, police detained freelance journalist Thomas Haulotte and held him overnight after he followed activists putting up posters with messages denouncing the far right. In September 2025, police in Nouakchott, Mauritania arrested two Al Akhbar.info journalists, Mohamed Abdallah Ould al-Moustapha and Aboubakar Ould Mohamed Vall, while they covered a sit-in outside gas company SOMAGAZ. They were released without charge after being held for three hours. In India, journalist Mujeeb Shaikh was detained on 6 March 2025 and held overnight while covering a peaceful women-led demonstration against war in Hyderabad. In May 2025 in Ottawa, Canada, Ramona Murphy, a North Star volunteer journalist, was detained along with 12 protesters while covering a protest at the Defence and Security Trade Show. The protest denounced the complicity in Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza of some companies at the event that allegedly sell equipment to the Israeli military.

Activism targeted

Detention of HRDs was the third most common civic space violation globally, documented in at least 71 countries. Authorities use detention of HRDs as a tactic to discourage activists from continuing their work, including on raising issues of public interest. Detention of HRDs features in the top the violations in Africa South of the Sahara, the Americas, Asia Pacific and MENA regions.

HRDs working on environmental, Indigenous and land rights, labour rights and women’s rights, along with artivists, were among those targeted. Additionally, human rights lawyers have been subjected to detention.

HRDs working on environmental, Indigenous and land rights face government harassment, including arbitrary detention and prosecution. In Bangladesh, authorities arbitrarily detained prominent Indigenous leader and HRD Ringrong Mro, of the Mro community in Lama Upazila, Bandarban, in February 2025, in relation to a 2022 complaint filed by Lama Rubber Industries Limited. The HRD had been at the forefront of grassroots efforts to protect the environment and Indigenous lands, including from corporate encroachment and land grabbing.

In February and March 2025, authorities in Mendoza, Argentina detained Mauricio Cornejo and Frederico Soria, charging them under the Criminal Code for their environmental activism, with prosecutors alleging they used their activism to ‘instil fear’ and obstruct the San Jorge Mining Project. Both are part of the Assembly of Self-Convened Neighbours of Uspallata, a group that has peacefully opposed the mining project. They were released in April 2025.

In Paraguay, police arbitrarily detained Vidal Brítez Alcaraz, president of the Association of Yerba Mate Growers of Paso Yobái, in March 2025, on unfounded charges of ‘grave coercion’. The charges relate to a January 2025 incident when a judicial order authorised trucks carrying mining waste to enter the property of a yerba mate producer. Police escorted the trucks, prompting a confrontation in which residents reportedly threw stones. Despite clear evidence confirming that Brítez was at home five kilometres away, prosecutors indicted him alongside five other environmental defenders.

In the Philippines, Asia’s deadliest country for environmental activists, authorities continue to smear activists as communists and detain them on baseless accusations under draconian laws, including the 2020 Anti-Terrorism Act and the Terrorism Financing Prevention and Suppression Act. In April 2025, six prominent Cagayan Valley activists, including environmental activist and journalist Deo Montesclaros, were charged in cases of financing terrorism.

Revoking citizenship as a threat or punishment for activism

According to Oman’s new citizenship law, citizenship shall be revoked for verbally or physically offending the Sultanate or the Sultan of Oman or for belonging to an organisation that embraces principles that harm the state’s interests. In Cambodia, the government now has the power to revoke the citizenship of anyone found guilty of conspiring with foreign countries to harm the national interest. In Hungary, dual citizens may now be stripped of their citizenship for up to 10 years if they are deemed to pose a threat to public order, safety or national security. In January 2025, Nicaragua’s National Assembly approved sweeping constitutional changes granting unlimited powers to President Daniel Ortega and Vice-President Rosario Murillo, including a revision to article 24 that enables the arbitrary removal of nationality. In May 2025, lawmakers adopted further amendments, imposing automatic loss of citizenship for Nicaraguans who acquire another nationality.

Lawyers, including human rights lawyers, have increasingly been targeted with arrests, often in response to their criticism of authorities or defence of activists and journalists. In Burkina Faso, in 31 August 2025, armed men claiming to be gendarmes arrested prominent lawyer Ini Benjamine Esther Doli on accusations of treason and insulting the head of state, over a Facebook post criticising the human rights record of the military junta under President Ibrahim Traoré. In Sudan, police arrested Abubakr Elmahi, lawyer for HRD Abubakr Mansour Abdela, on 1 October 2025, just days before Abdela was sentenced to death. Abdela was convicted for ‘offences against the state’ and ‘waging a war against the state’ under the Criminal Act, believed to be related to the humanitarian assistance he provided since the start of Sudan’s civil war by handing out medicines from his brother’s pharmaceutical company.

In Turkey, Fırat Epözdemir, a board member of the Bar Association, was detained on 23 January 2025 on returning from an advocacy visit to the Council of Europe. He was charged with alleged ‘membership of a terrorist organisation’ and ‘making propaganda for a terrorist organisation’. In February 2025, the Bar Association’s president and 10 other board members were also charged with ‘dissemination of misleading information’ and terrorism, punishable with up to 12 years in prison, in a separate case.

Artivists around the world have faced detentions and prosecutions in retaliation for their work. In China, authorities have cracked down on artists and other creative workers whose work or views the Communist Party sees as potentially subversive.

Among those detained are prominent musician Fei Xiaosheng, who has publicly supported the Hong Kong democracy movement, and Tibetan singer Tzukte, popularly known as Asang, for having sang a song eulogising Tibet’s exiled spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama. In Afghanistan, the Taliban arrested cultural activist and poet Sayed Alam Hashemi on 16 February 2025. While the official reasons for his arrest are unknown, sources believe it is in relation to his poetry. On 30 December 2024, police in Malaysia arrested artist and activist Fahmi Reza under the Sedition Act, used to criminalise expression and dissent, after he created a mural with a satirical graphic of Sabah Chief Musa Aman in the city of Kota Kinabalu. He was remanded in custody for a day before being released.

Others have been detained for expressing critical views on social media. In Yemen, Fawzi Ahmed Obaid, an online activist arrested in September 2015 by a Houthi-affiliated group for his Facebook posts, remains held incommunicado in an underground cell run by the Security and Intelligence Service in Sana’a. His family has never been allowed to visit him, and his case has never been presented before a court for trial. In Libya, activist Haitham Al-Werfali was arbitrarily detained in December 2024 after posting criticism of eastern Libyan authorities on Facebook. He was released four days later without legal process.

Authorities have also detained trade union leaders and members in retaliation for their advocacy for labour rights and for organising strikes. In Côte d’Ivoire, hooded men arrested Ghislain Duggary Assy, a teacher and communication secretary for the Movement of Teachers for the Dignity Dynamic Union, on 2 April 2025 in Abidjan, after a coalition of unions called for a teachers’ strike. A court sentenced him a few days later to two years in prison for obstructing the operation of the public service, a conviction an appeal court upheld in July 2025. In March 2025, plainclothes agents arrested Ali Mammeri, activist in the Hirak protest movement and president of the Syndicat national des fonctionnaires de la culture trade union in Oul El Bouaghi, Algeria. Mammeri had been targeted with reprisals and threats of legal action after organising a unionisation campaign in the cultural sector in 2024.

Human rights monitoring of protests has also led to arbitrary arrests. In Ecuador, police officers arbitrarily detained Jafet Guzmán and Miguel Ángel Pérez of the Regional Foundation for Human Rights Advice in Quito while they monitored protests against President Daniel Noboa, despite the two clearly identifying themselves as observers. In May 2025, HRD and Indigenous poet Esteban Binns Carpintero was arbitrarily detained while documenting a peaceful protest in Tolé, Panama. In El Salvador on 12 May 2025, police arbitrarily detained community leader José Ángel Pérez during a peaceful vigil held outside the presidential residence by over 300 families from the El Bosque community to oppose their imminent eviction. The next day, authorities detained environmental defender Alejandro Henríquez, the cooperative’s legal representative, in connection with the protest. Both were charged with public disorder and obstruction of justice and remain in custody.

Women HRDs and LGBTQI+ activists remain vulnerable to attacks and detentions. In Kazakhstan, police detained Zhanar Sekerbayeva and Gulzada Serzhan, co-founders of feminist and LGBTQI+ civil society organisation (CSO) Feminita, after their event was stormed by anti-feminist agitators.

Both were fined for leading an unregistered organisation. Authorities have also repeatedly rejected Feminita’s registration. In Morocco, authorities arrested WHRD and blogger Saida El Alami on 1 July 2025 and in September sentenced her to three years in prison and a hefty fine for ‘insulting a legally organised body, disseminating false allegations and insulting the judiciary’.

In Venezuela, in early August 2025, police detained lawyer and WHRD Martha Lía Grajales after she participated in a solidarity activity in front of the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Office in Caracas.

Transnational repression, encompassing a range of tactics, including illegal abduction, intimidation and surveillance, used by governments to suppress dissent of their nationals and diaspora beyond their borders, has seen an escalation this year, with cases documented in several regions. The trend of transnational repression in Asia Pacific has continued in 2025, and the CIVICUS Monitor has documented cases of government cooperation to unlawfully arrest, illegally abduct, deport and in some case kill dissidents abroad in East and Horn of Africa, West Africa, MENA and Nicaragua and Venezuela (see regional chapters).

Restrictive legislation and regulation: a persistent and pervasive trend

ADD ICON

In 2025, the CIVICUS Monitor documented the adoption or proposal of restrictive laws and regulations affecting civic freedoms in at least 66 countries, making restrictive laws the ninth most prevalent global civic space violation.

The adoption and proposal of restrictive laws is an ongoing multi-year trend. The UN, regional human right bodies and numerous CSOs have urged states to halt the proliferation of laws that unduly restrict civic freedoms, calls that have largely gone unheeded. Governments continue to introduce new restrictive laws across all regions and across every category of civic space rating, undermining freedoms of association, expression and peaceful assembly. The CIVICUS Monitor tracks both adopted and proposed restrictive laws, as proposed laws can influence civic space and require significant civil society effort to oppose them.

This analysis covers measures adopted or introduced in 2025, although many restrictive laws passed in previous years remain in force and continue to shape civic space.

Disregard for civil society’s input when drafting and adopting legislation

The CIVICUS Monitor recorded multiple cases in which laws affecting civil society were drafted through processes that excluded CSOs or ignored their input. For instance, in 2025, Benin adopted a revision of its NGO law without inviting CSOs to review or comment on the draft. In Kyrgyzstan, although extensive consultations were held with media representatives regarding a new media law, the version ultimately adopted discarded key changes previously agreed on. Parliament passed the law hastily, combining second and third readings in a single day at the end of its session. In Canada, sweeping provincial and federal omnibus laws on infrastructure projects were adopted without the free, prior and informed consent of Indigenous peoples who will be affected by these new measures and whose consultation is legally mandated.

LAWS RESTRICTING FREEDOM OF ASSOCIATION

Foreign agents laws have proliferated. These laws require organisations that receive foreign funding to register and label themselves as foreign agents. On top of administrative burdens, foreign agents laws hinder fundraising and usually impose punitive taxes on foreign grants, and they also stigmatise organisations. Russia, which pioneered the contemporary model of foreign agents legislation, further expanded its law this year, as did India.

Several states have introduced or threatened to introduce comparable measures in 2025, including Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Central African Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Georgia, Hungary, Israel, Kazakhstan, Paraguay, Slovakia and Zimbabwe. In El Salvador, the impacts of the adoption of such laws were immediately visible as established human rights organisations and journalists’ associations closed down or were forced to move operations abroad.

Many governments also adopted or proposed laws that increase compliance requirements and impose new restrictions on CSOs under the guise of improving transparency, adding barriers to the establishment, operation, funding and range of activities of CSOs. In 2025, this happened in Azerbaijan, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Nepal, the Netherlands, Thailand, Vietnam, Zambia and, through multiple bills, in Ecuador. These measures typically expand the supervisory powers of state authorities, including the ability to restrict their operations, as in Greece, limit their access to funding, as in Hungary, or to dissolve them, as in Venezuela.

Other governments amended existing laws with vague or overly broad provisions that can be used to target activists and organisations. Examples include revisions to counter-terrorism legislation in Belarus, Pakistan and Sierra Leone and to counter-extremism laws in Russia.

LAWS RESTRICTING FREEDOM OF PEACEFUL ASSEMBLY

In 2025, several countries adopted legislation that further restricts the right to peaceful assembly. Between January and April 2025, at least 41 US states introduced bills to impose new restrictions on protests. In Slovenia, draft Amendments to the Public Assemblies Law were introduced that would increase the personal data required from organisers and expand their administrative obligations. In Cyprus, demonstrations are now subject to a mandatory seven-day notification period and organisers are required to provide extensive information in advance.

Some laws restrict protest topics. Hungary has introduced prohibitions on organising or attending events deemed to violate the country’s child-protection laws, and a recent constitutional amendment authorises the government to ban public events organised by LGBTQI+ groups. In Myanmar, ahead of an undemocratic December 2025 election, protesters must now contend with a new ban on any speech or organisational activity considered to be aimed at ‘destroying a part of the electoral process’.

Governments are increasingly seeking to restrict locations where protests may occur. In Kenya, the parliament sought to propose a law seeking to e prohibit demonstrations within 100 metres of key state institutions, including parliament, State House and court premises. In Canada, various provinces and municipalities are adopting ‘bubble laws’ prohibiting peaceful protest in the vicinity of social infrastructure such as places of worship and schools.

Even more concerning are the new charges or harsher penalties proposed or added to legislation. Georgia and Italy passed sweeping legal packages that further restrict fundamental rights and freedoms, such as penalties for participating in unauthorised demonstrations. In Uzbekistan, organising and participating in ‘mass unrest’ was already criminalised, but the new version of the Uzbek Criminal Code adds penalties for organising training for mass protests. The UK criminalised the use of face coverings at specific protests and created additional offences in relation to protest.

LAWS RESTRICTING FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION

The CIVICUS Monitor recorded several measures that undermine the independence of media outlets, broaden the basis for prosecuting journalists or work to prevent them doing their jobs in accordance with the rules of their profession. In Cyprus, a draft law could potentially result in lifting the right of journalists to protect their sources, or allow the search of journalists’ electronic devices, homes and offices. The Central African Republic reintroduced criminal penalties for professional misconduct, extending prosecution beyond content authors to editors-in-chief, managing editors and presenters.

Several governments introduced measures to weaken the independence of media outlets or media regulators, including in Ethiopia, where amendments mean the Media Authority no longer needs to include civil society representation and the prime minister rather than parliament appoints its director general. In Nicaragua, the removal of the constitutional ban on press censorship gave the government broader authority to restrict independent media. In other countries, authorities have sought greater control over media outlets by demanding detailed financial disclosures, as seen in Peru, and editorial programming information, as amendments proposed in Lebanon, or attempting to dictate content directly, as in Zimbabwe.

2025 saw the adoption or discussion of several cybersecurity bills and bills regulating social media. While these laws can pursue legitimate aims such as protecting critical infrastructure and personal data and deterring disinformation, several governments introduced bills or laws that give authorities excessive powers without adequate oversight. These laws contain vague definitions and provide a basis to delete public interest information or criminalise online speech and silence dissent, particularly as new laws have been introduced in countries with serious civic space restrictions. Some laws clearly seem to have draconian intentions, including in Zambia, where new cybersecurity laws retain vague definitions which could enable state agencies to undertake unchecked surveillance. In some cases, restrictive cybersecurity laws were amended to further control and criminalise online speech, such as in Pakistan, where amendments to the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act were adopted in January 2025.

As a result of changes in laws, media organisations could now be requested to delete content deemed ‘incomplete’, as in El Salvador, or ‘against the ideology of the country’, as in Pakistan, and under the threat of being blacklisted or fined, as in The Gambia. China increased the penalties for failure to adhere to its already strict surveillance and censorship imperatives, while Myanmar’s Social Media Bill would penalise the unauthorised use of VPNs that people use to circumvent internet restrictions, access information and share information internationally.

In Israel, police obtained the power to use cameras and microphones in personal electronic devices. In Hong Kong, the Commissioner’s Office obtained the right to request private companies to provide unspecified ‘relevant information’ if it suspects an offence has occurred, without need for a warrant.

Bills with similar vaguely worded provisions, criminalising the spreading of false news or expressions that are deemed defamatory are currently being discussed in Angola, Barbados and Nepal.

LAWS DIMINISHING PUBLIC SCRUTINY

While authorities assume increasingly broad powers based on vague concepts, the public’s rights to participate or access information are being reduced. This was observed in Malta, where, despite widespread mobilisation, the Criminal Code was modified to make it more difficult for citizens to request an investigation into potential corruption. In Vanuatu, the Right to Information Act was amended to restrict public access to decisions made by the Council of Ministers. In Kyrgyzstan, the independent body mandated to monitor detention facilities and prevent torture, which closely worked with civil society, was dissolved.

Digital repression

Digital technologies have transformed how people and CSOs engage in public life, enabling unprecedented opportunities for advocacy, civic participation and mobilisation. Social media, for example, played a key role in helping to mobilise 2025’s youth-led protests. But at the same time, there has been a troubling rise in violations of online freedoms targeting CSOs, HRDs, journalists and media.

In 2025, at least 11 per cent of civic space violations documented by the CIVICUS Monitor had a digital component. This included internet restrictions, such as internet and social media shutdowns, online censorship, such as authorities blocking websites and URLs, arrest and prosecution of HRDs and journalists for online speech, online intimidation and harassment, the adoption of laws criminalising online expression and platform-enabled restrictions, such as algorithmic suppression and content removal driven by state pressure. However, CIVICUS Monitor figures likely underestimate digital civic space restrictions as some violations, such as coordinated content manipulation during elections and protests, coordinated disinformation and misinformation campaigns, online threats, surveillance and trolling, are either not systematically documented or hard to track.

Internet restrictions

Governments continue to apply internet restrictions, particularly around elections and during protests, as a tactic to deter mobilisation and stifle dissent. Internet shutdowns, including complete blackouts and the selective blocking of mobile data and social media platforms, have become a powerful tool to disrupt the organisation of protests, limit the sharing of information and prevent the documentation of violations. In Cameroon, internet outages affecting several regions were reported from 22 October 2025, in a tense context where protests followed the undemocratic election that granted President Paul Biya an eighth term.

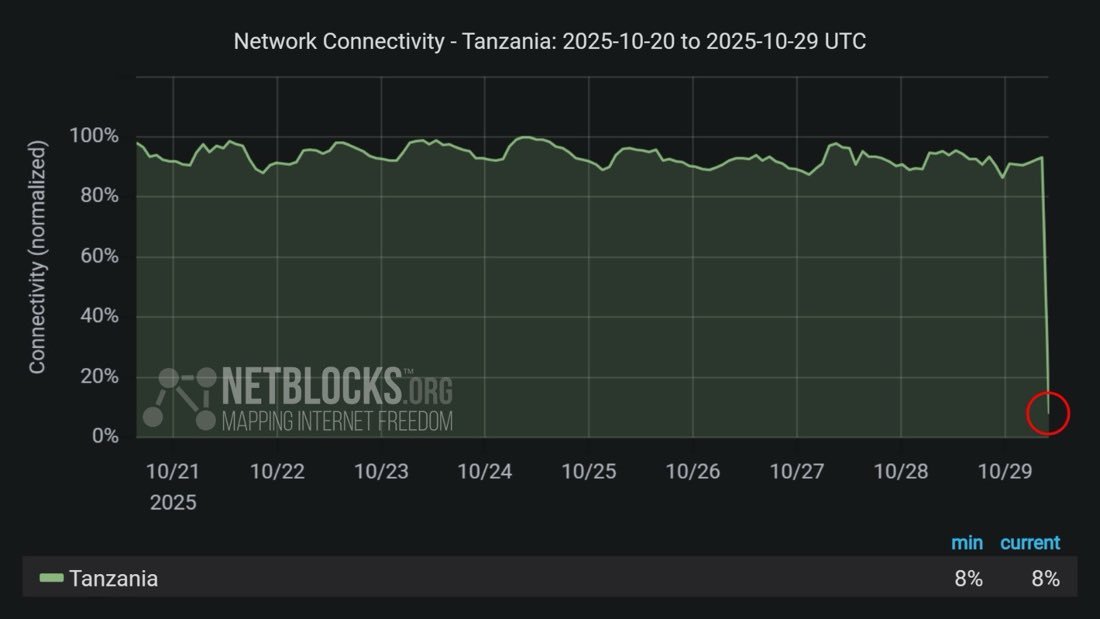

Between 29 October and 3 November 2025, NetBlocks confirmed a nationwide internet shutdown in Tanzania during a non-competitive general election and mass post-election protests. The CIVICUS Monitor has also documented restriction of social media platforms, including messaging apps. In January 2025, South Sudan’s National Communication Authority ordered all internet service providers to block access to social media for between 30 and 90 days.

The media regulator claimed the temporary blanket social media ban aimed to curb the spread of videos showing alleged killings of South Sudanese nationals in Sudan, which sparked violent protests and retaliatory attacks on Sudanese nationals. In May 2025, Vietnam ordered telecommunication service providers to block the messaging app Telegram on accusations that Telegram did not cooperate in combating alleged crimes committed by its users.

In September 2025, the government of Nepal ordered the Nepal Telecommunications Authority to block 26 unregistered social media platforms, including Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), YouTube, and Instagram. The decision followed repeated deadlines under the 2023 Social Media Operation Directive, which requires platforms to register locally, appoint liaison officers, and designate grievance handlers. While TikTok and Viber complied, most global platforms refused, triggering the suspension order. This ban on social media led to the events starting on 8th September 2025, when mostly youth protestors took to the streets across Nepal - including Kathmandu, Pokhara, Butwal, and other major city centres - demanding an end to corruption and the lifting of the aforementioned ban.

Authorities are increasingly using bandwidth throttling, when internet providers intentionally slow down internet speed, and selective shutdowns, when internet restrictions are targeted at specific applications, functionalities or regions, to discourage protesters from mobilising or sharing information. In Turkey during the March 2025 mass protests, authorities imposed extensive bandwidth throttling across all major social media and messaging platforms. Services including Instagram, Signal, Telegram, TikTok, WhatsApp, X/Twitter and YouTube were slowed significantly, with some users reporting restrictions lasting up to 42 hours. In Sudan in July 2025, the Telecommunications and Post Regulatory Authority announced the blocking of WhatsApp’s voice and video call feature, citing security concerns and the need to protect the ‘higher interests of the state’.

Surveillance and spyware

Authorities have also used surveillance including spyware against HRDs, journalists and protesters. In February 2025, reports surfaced in Italy that investigative journalist Francesco Cancellato, who exposed pro-fascist elements in the youth wing of far-right Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s party, and two refugee rights activists who have been vocal in denouncing Italy’s complicity in human rights violations in Libya, were targeted by Graphite, a military-grade spyware sold exclusively to governments. In Serbia in December 2024, investigations revealed that the Security and Intelligence Service had used spyware to monitor the phones of activists and journalists, including a student participant in sustained anti-government protests that began in November 2024.

In China, which has an extensive and sophisticated internet censorship regime, the implementation of a new government internet identification requirement, mandating users to register through the National Online Identity Authentication App, will further constrict online anonymity and increase opportunities for authorities to spy on and control online speech. In the USA, the Catch and Revoke programme, a joint initiative of the Department of Homeland Security, Department of Justice and State Department, is using AI to monitor the social media accounts of thousands of student visa holders, scanning for content interpreted as sympathetic to Hamas or other designated groups. Non-state actors are also involved in surveillance. In August 2025, the University of Melbourne, Australia, was found to have breached privacy laws by using information to track students involved in a 2024 Palestine solidarity protest.

Online censorship

Cases of online censorship include the arbitrary removal or blocking of online content. In Romania, ahead of the May 2025 presidential election rerun, after authorities annulled the 2024 vote on the grounds of foreign interference by Russia, authorities introduced draconian online content laws to curb the spread of Russian disinformation in support of far-right candidates. Under emergency regulations introduced in January 2025, social media users, including voters as well as candidates and political influencers, were labelled as ‘political actors’ if they mostly posted political content, subjecting them to strict rules on political advertising and facilitating the removal of content. By 4 April 2025, over 4,000 content-removal orders had been issued, mostly targeting TikTok. In Algeria, the website of CSO Riposte Internationale, which provides information on human rights and publishes investigations and reports on the repression of journalists and freedom of expression restrictions, was made inaccessible for internet users in April 2025.

As well as blocking and removing content, authorities have issued directions and notices to correct content. In Singapore, the government has widely used the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act to limit freedom of expression of journalists and media. For example, in December 2024, the government issued correction directions to Bloomberg and several local outlets after they reported on luxury property purchases involving trusts and opaque ownership structures. Authorities claimed the articles contained inaccuracies, obliging four outlets to display government-mandated correction notices and link to official clarifications.

Platform-enabled censorship has seen removal of social media content and accounts, often following state pressure. In July 2025, it was reported that authorities in India had ordered X/Twitter to block over 2,000 accounts, including two accounts belonging to Reuters News. The two accounts were suspended, displaying a message that they had been ‘withheld in IN in response to a legal demand’. In May 2025, Indian authorities ordered the blocking of a further 8,000-plus X/Twitter accounts, including Kashmir-based news outlets Free Press Kashmir, the Kashmiriyat and Maktoob Media, which focuses on human rights. In Ecuador, Facebook removed multiple publications from three digital media outlets – Mumarta, Radio Reloj and Radio Voz de Upano – restricting the circulation of their reports on alleged irregularities in public contracting processes in the Municipality of Morona Canton. In January 2025, Meta removed content from Chilean journalist Daniel Matamala’s Instagram account following publication of an opinion column in La Tercera, in which he critically examined the role of digital platforms in disseminating disinformation, facilitating hate speech and shaping public opinion.

Criminalisation of online speech

The CIVICUS Monitor has documented many cases of criminalisation of online speech, including criminal actions against people for online expression, typically using vague and broad legal provisions on disinformation and misinformation, false information and cybercrimes, among others. On 20 March 2025, Qatar’s Criminal Court sentenced internet activist Umm Nasser to three years in prison and a fine of 50,000 Qatari Riyals (approx. US$13,650) on charges of spreading false rumours, managing a social media account to spread such rumours and disrespecting the Qatari judiciary. In Nepal in August 2025, journalist Dil Bhusan Pathak was charged with publishing illegal material under the 2008 Electronic Transactions Act, which is regularly used to stifle online commentary and prosecute journalists. The charges followed an allegation on Pathak’s YouTube channel that Jaiveer Singh Deuba, the son of two powerful Nepalese politicians, was linked to questionable deals.

Online intimidation and threats against HRDs and journalists

Over 30 per cent of acts of intimidation and threats against journalists documented by the CIVICUS Monitor were made online. Online threats and violence are likely under-reported but have proliferated with the burgeoning of social media, and these have gendered dimensions with intimidation and threats specifically targeted against women. In January 2025, the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders, Mary Lawylor, reported having received news of an online smear campaign against Pakistani WHRD Professor Amar Sindhu, a member of a women activists’ group, poet and pioneer of a café, Khanabadosh, where activists and artists gather. Sidhu has been subjected to cyber-harassment and online intimidation. On 5 May 2025 in Ukraine, Vilne Radio journalist Yevhen Vakulenko reported receiving insulting and threatening Facebook messages from Kyiv city military administration spokesperson Yevhen Yevlev, who allegedly threatened to ‘break his face’ and called him an ‘enemy of the Ukrainian people’. The messages followed a Vilne Radio investigation alleging possible corruption involving Yevlev’s father. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) freelance journalist Daniel Michombero, who is based in Goma, received threatening replies in January 2025 after posting a photo of his family on X/Twitter, accusing him of spreading “fake news” and including suggestions that he should flee to Rwanda along with other refugees, or seek protection from the M23 insurgent forces to escape retribution.

Doxxing, the revealing of identifying information without people’s consent, is another form of online intimidation against activists and journalists. On 28 March 2025, at least 18 journalists were subjected to a doxxing attack in Chiapas, Mexico when a Facebook page and a website published their names, photographs, details of their employers and, in some cases, unsubstantiated allegations of links to organised crime. In the USA in February 2025, Palestinian American Khan Sur, who was arbitrarily detained the following month, and his wife, Mapheze Saleh, were the targets of coordinated online smear campaigns and doxxing after publicly criticising Israel’s genocide in Gaza.

Other tactics documented include account and website takedowns, algorithmic surveillance, coordinated online harassment, often with gendered impacts, disinformation campaigns and spyware, offering a growing and evolving threat to civic space.