Europe and Central Asia

Rating Overview

In the past year, civic space has continued to be eroded in Europe and Central Asia. Of 54 countries, civic space is now rated as open in 19, narrowed in 19, obstructed in seven, repressed in three and closed in six.

In 2023, Europe grappled with the political and economic fallout of Russia’s war on Ukraine. Widespread protests erupted in response to rising energy prices and cost of living increases in various European Union (EU) countries, including Belgium, the Czech Republic, Greece and Portugal. Climate groups vehemently opposed shifts in energy policies adopted by EU countries in response to the conflict’s disruption of the energy market. In response, European states escalated repression of environmental activists, responding to non-violent protests and civil disobedience actions with arrests, prosecutions and intimidation.

Country ratings in Europe and Central Asia have deteriorated further overall. Bosnia and Herzegovina and Germany, an EU member state, both saw a downgrade in their ratings. Kyrgyzstan, once viewed as the most democratic country in Central Asia, also witnessed a downgrade. As a result, all Central Asian countries are currently classified as either repressed or closed.

Bosnia and Herzegovina, which was added to the CIVICUS Monitor Watchlist in September 2023 due to a rapid decline in its civic space, has moved from narrowed to obstructed, joining Serbia, previously the only country in the Western Balkans with this rating. The ongoing political crisis triggered by threats of secession by the country’s Serb-majority entity, Republika Srpska (RS), has increased pressure on civil society and the media. During the year, RS President Milorad Dodik sought to ‘cleanse Bosnia and Herzegovina of foreign influence’ by introducing laws to silence dissent, including a Russian-style ‘foreign agent’ law and the reintroduction of criminal defamation into the legal system. Violence and threats against journalists and activists, particularly targeting LGBTQI+ rights advocates, continue to be common across the country.

In 2023, Germany experienced a concerning decline in civic space, largely due to the repressive measures implemented by the authorities to curtail the activities of environmental activists, leading to the country’s ranking shifting from open to narrowed. In January, police used excessive force to remove some 700 protesters who had been occupying the village of Lützerath, whose residents had been evicted to allow for the expansion of a coalmine. The Letzte Generation (Last Generation) movement, known for its high-profile civil disobedience actions in airports, roads and museums, has been particularly targeted, with home raids, asset seizures and the blocking of its online platform. Members of the climate group are now facing the serious charge of forming a criminal organisation in connection with their non-violent protests targeting public infrastructure

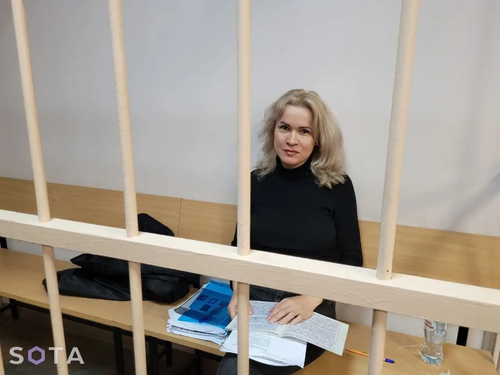

Kyrgyzstan’s civic space assessment shifted from obstructed to repressed due to an escalating crackdown on civil society and media, emphasised by the introduction of repressive draft laws. Despite strong objections from the international community and civil society, as of November 2023, parliament was in the process of adopting a law on NGOs with provisions similar to those in Russia’s ‘foreign agent’ legislation. Another draft law currently under consideration provides for excessive state regulation of media and online platforms, raising concerns it could be used to target critics. The number of politically motivated criminal prosecutions has increased, further shrinking the space for critical expression. In one notable case in October 2022, Kyrgyzstani authorities arrested almost 30 journalists, bloggers, HRDs and public figures who had spoken out against a land swap with Uzbekistan over the Kempir-Abad water reservoir. A year later, some of the defendants in the case are still in pretrial detention and the trial is taking place behind closed doors.

‘Foreign agent’ laws

Global conflicts and political instability in Europe and Central Asia have led to a proliferation of ‘foreign agent’ and ‘foreign influence’ laws, ostensibly to protect national sovereignty, but often with far-reaching implications for civil society activity.

March 2023 saw thousands flooding the streets of Georgia to denounce a restrictive draft law on ‘transparency of foreign influence’. The law mandated CSOs that receive over 20 per cent of their income from foreign sources to register as foreign agents, with heavy fines for non-compliance. When the law was put on the parliamentary agenda on 7 March 2023, over 10,000 protesters in Tbilisi voiced their opposition, resulting in clashes with security forces, which used teargas and water cannon. In response to the protests, the government withdrew the law from parliament pending further public debate.

On 23 March 2023, the government of the RS in Bosnia and Herzegovina adopted a draft law to establish a special register for CSOs supported from abroad. These organisations are to be designated as ‘agents of foreign influence’ and will be subject to stricter control and a vague ban on ‘political activities’, making advocacy a punishable offence. Parliament passed the first reading of the draft in September 2023.

In Kyrgyzstan, a ‘foreign agent’-style draft law was submitted to parliament in May 2023. It would require CSOs that receive international funding and that engage in broadly defined ‘political activities’ to register as ‘foreign representatives’, with the risk of suspension of their activities for up to six months without a court decision as the penalty for non-compliance. Those that do register would be subjected to burdensome reporting obligations and unannounced inspections. In October 2023, the draft law passed its first reading. In neighbouring Kazakhstan, the government introduced a public record of foreign-funded CSOs in a move clearly aimed at stigmatising such groups.

In May 2023, the EU presented its ‘Defence of Democracy’ package, which included a directive on ‘foreign interference’ that raised concerns among civil society across Europe. The proposed directive would require CSOs to disclose funding from sources outside the EU and subject them to strict registration and reporting restrictions. Over 200 European CSOs signed a letter opposing the proposal, arguing that it undermines the EU’s credibility in opposing the use of similar measures to stifle civil society within or outside its borders. In July 2023, the European Commission responded with assurances that a thorough impact assessment would be undertaken before any such legislation was implemented.

Russia continues to stifle civil society activities through its notorious ‘foreign agent’ legislation, designating international CSOs Transparency International and the World Wide Fund for Nature as ‘undesirable’, and their Russian branches as ‘foreign agents’. In neighbouring Belarus, as of May 2023, over 800 organisations were undergoing forced liquidation, as part of the campaign announced in 2021 by President Aleksandr Lukashenko as a ‘mopping-up operation’ against ‘bandits and foreign agents’.

Civic Space Restrictions

In Europe and Central Asia, the most common violations of civic freedoms documented in 2023 were intimidation, detention of protesters and disruption of protests, censorship and the passing of restrictive laws.

Intimidation

Intimidation was the main violation of civic space in Europe and Central Asia during the reporting period, documented in at least 28 countries and most often used against journalists and media. Other groups particularly affected were environmental activists, refugee rights activists and women HRDs.

Attempts at intimidation often took the form of attacks on the property and premises of media outlets and CSOs. In Banja Luka in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the cars of two journalists, Nikola Morača and Aleksandar Trifunović, were vandalised after they spoke out against the proposal to recriminalise defamation. Not long after, unknown people vandalised the premises of a social centre in the city, smashing windows and stealing an LGBTQI+ Pride flag. In Kazakhstan, a series of acts of intimidation and harassment targeting independent media were reported ahead of March 2023 parliamentary elections. For example, the car of journalist Dinara Yegeubayeva was set ablaze near her home in Almaty and the office of the Elmedia online outlet was attacked six times by unknown perpetrators.

Legal intimidation through strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs) filed by public officials, companies and powerful individuals continued to occur frequently in Europe and Central Asia. Such lawsuits were documented in multiple countries, including Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece and Italy.

In Serbia, Aleksandar Šapić, the Mayor of Belgrade, filed two lawsuits against the Balkan Investigative Research Network over articles about his real estate holdings. Other forms of legal harassment were recorded, as states have initiated criminal and administrative proceedings against HRDs in order to intimidate them. In May 2023, Greek media reported that prominent HRD Panayote Dimitras was under investigation by the anti-money laundering authority for embezzlement of EU funds. Dimitras had previously been questioned by authorities in December 2022 after he was charged with ‘establishing a criminal organisation with the aim of facilitating the illegal entry and stay of third-country nationals in Greece’ in connection with his work with refugees.

In Central Asia, prosecution continued to be used frequently as a means of intimidation and suppression of dissent, and prosecutions of journalists and HRDs are some of the most common violations in the region. Particularly concerning was the use of extremism charges in Kazakhstan and Tajikistan against government critics, including HRD Manuchehr Kholiknazarov and opposition party leader Marat Zhylanbaev, and the pursuit by authorities in Turkmenistan of the forcible repatriation of outspoken activists abroad, accompanied by pressure on their relatives within the country. Notably, Turkey-based Turkmen activist Dursoltan Taganova reported intimidation targeting her 12-year-old son who lives in Turkmenistan, who security services questioned and attempted to recruit as an informant. In Tajikistan’s Gorno-Badakhshan (GBAO) region, security officials have reportedly summoned civil society representatives and threatened to bring criminal charges against them or their relatives unless they ‘voluntarily’ close their organisations. The number of CSOs in Tajikistan that have been shut down or pressured into closing significantly increased in 2023.

Protesters detained

The detention of protesters was the second most common violation in Europe and Central Asia, documented in at least 22 countries, while protests were disrupted in no fewer than 18 countries. The most common protest drivers were women’s rights, environmental rights and labour issues. Environmental and climate protests, and protests against war and conflict, were more likely to encounter restrictions.

As part of the crackdown on environmental activists, climate protests in European countries were increasingly broken up and protesters arrested. In November 2022, around 500 climate activists staged a dramatic protest at Schiphol Airport in the Netherlands, occupying the runway, chaining themselves to aeroplanes and sitting on the tarmac. The police responded forcefully, arresting over 200 activists and using physical violence against those chained up, resulting in at least one hospitalisation. In March 2023, police in The Hague used water cannon to disperse activists on the A12 motorway, resulting in 700 arrests, all but three of whom were later released. During another blockade of the A12 motorway in May, 1,579 people were arrested with 40 people charged.

In May 2023 in Belgium, 14 international activists occupying a liquefied natural gas terminal were arrested for trespassing and released after 48 hours. During the year, climate activists were also detained in France, Germany, Italy, Norway and the UK for non-violent civil disobedience actions. Peaceful environmental protests in Azerbaijan and Serbia were also met with excessive police force.

Amid a wave of protests in France, arrests of protesters were often accompanied by widespread and brutal police violence, causing concern among the EU, UN and international human rights organisations. In March, police used disproportionate and indiscriminate force to disperse around 30,000 environmentalists protesting against the construction of irrigation mega-basins in Sainte-Soline. Subsequently, during riots that took place between 27 June and 4 July following the shooting of an unarmed teenager by police, more than 3,000 people were arrested. Those arrested had an average age of 17, with some as young as 12.

Throughout the year, anti-war sentiment remained an important catalyst for protests, with protests related to war and conflict spanning at least 17 countries in Europe and Central Asia in 2023. In February, demonstrations were held across Europe to commemorate the first anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In Russia, peace activists marked the date with symbolic acts such as laying flowers at statues of Ukrainian poets and solitary pickets. However, the Russian authorities reacted with repression, with over 50 arrests. In addition, since October 2023, several European countries, including France, Germany and the UK, have imposed restrictions on mass protests in solidarity with Palestine amid Israel’s assault on Gaza.

In Central Asia, a widespread lack of accountability continued for severe human rights violations stemming from the suppression of anti-government protests in 2022. These incidents, notably violently supressed protests known as ‘Bloody January’ in Kazakhstan, unrest in the GBAO in Tajikistan and events in the Republic of Karakalpakstan in Uzbekistan, have seen insufficient efforts to investigate alleged human rights violations against protesters. Government attempts to investigate these allegations and hold those responsible to account have lacked independence, thoroughness and efficiency. As a result, a climate of impunity prevails, allowing serious human rights violations such as excessive force, torture and ill-treatment to continue unchecked.

Censorship

Censorship is a prominent violation in Europe and Central Asia, with more than 50 incidents reported across 26 countries. Over the year, authorities targeted the spread of ‘fake news’, ‘banned’ or ‘extremist’ content on social media platforms and often used these provisions to prosecute people who criticised military interventions and wartime human rights violations. In Russia and Belarus in particular, hundreds of people were arrested and imprisoned for speaking out against the war in Ukraine. For example, Igor Baryshnikov, a 64-year-old activist, was sentenced to seven and a half years in prison in Kaliningrad for spreading ‘fake news’ about the Russian army on Facebook. In the first month following Azerbaijan’s offensive in Nagorno-Karabakh on 19 September, which displaced more than 100,000 Armenians, over 20 people were arrested for criticising the ‘anti-terrorist operation’, mainly for disseminating ‘banned’ content.

Authorities in France, Germany and the UK announced their intention to deport all non-citizens perceived to be expressing support for Hamas in the aftermath of its terrorist assault on Israel. In the UK, students have been interrogated by the police for social media posts referencing Palestine’s ‘right to resist occupation’ and referring to Israeli settlers as ‘fascist’. Academics have also faced accusations of justifying Hamas militant attacks in online posts. In Berlin schools, state authorities have banned any ‘demonstrative behaviour or expression of opinion’ that could be understood as an expression of approval for attacks on Israel or terrorist activities, which in their view includes common pro-Palestinian symbols such as keffiyehs and stickers reading ‘Free Palestine’.

The few independent media outlets remaining in Central Asia were subjected to ongoing pressure and access to online content was restricted. Draft laws in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan risk increasing state control over media, while new blogging restrictions have been initiated in several countries. In Tajikistan, at least two independent outlets, the New Tajikistan 2 website and Pamir Daily News were banned as ‘extremist’ by court order, and in Kyrgyzstan, a request to close down the Kloop portal due to its critical reporting was pending in court as of November 2023. Extensive internet censorship continued in Turkmenistan, with thousands of websites arbitrarily blocked.

Environmental defenders

From the end of 2022, climate groups including Extinction Rebellion, Just Stop Oil and Last Generation organised increasingly high-profile civil disobedience actions across Europe, strategically blocking traffic, gluing themselves to roads and throwing food and washable paint at buildings and artworks. In response, politicians called for tough measures against these actions, leading to an increasingly harsh crackdown on environmental activists in the EU and beyond. The impact has seen people arrested, prosecuted and intimidated, in a wave of government action aimed at stemming the growing tide of climate activism.

In the Netherlands, two of the three Belgian activists from Just Stop Oil Belgium who glued themselves to Vermeer’s ‘Girl with a Pearl Earring’ painting in the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague were sentenced to two months in prison. In Italy, three activists from the Last Generation movement splattered the Senate building in Rome with washable orange paint, in protest against the government’s apparent reluctance to transition towards a carbon-neutral economy. The three activists were arrested and will face trial for vandalism, potentially facing up to three years in prison.

The charges levelled against environmental defenders have increased in severity, with authorities in some countries accusing them of organised crime and sedition, which enables the use of more repressive measures. In December 2022, German police raided the homes of 11 Last Generation activists and confiscated their phones and computers. On 24 May 2023, the investigation was widened with further raids, focusing on suspicion of establishing and supporting a criminal organisation, including direct involvement in the planning of crimes such as attempting to sabotage an Italy-Germany oil pipeline. In June 2023, the Munich Public Prosecutor’s Office confirmed that it had engaged in surveillance of Last Generation's communications, which included phones, email accounts and GPS location data. In the Netherlands, six activists were arrested for sedition in January 2023 for planning a blockade of the A12 motorway.

A worrying development is that in the UK, activists who were already on trial for these non-violent acts have additionally been charged with contempt of court for trying to explain their motives and beliefs to juries. Those who gather outside the court in their support face the same charge if they hold messages urging the jury to acquit. For example, 68-year-old Trudi Warner faces a prison sentence for holding a poster urging jurors in a climate trial to vote according to their conscience. A further 12 people are being investigated for contempt of court for displaying similar posters during another trial. Insulate Britain protesters Giovanna Lewis and Amy Pritchard were sentenced to seven weeks in prison for defying a judge’s order not to mention climate change during their trial.

| COUNTRY | SCORES 2023 | 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 |

| ALBANIA | 69 | ||||||

| ANDORRA | 86 | ||||||

| ARMENIA | 64 | ||||||

| AUSTRIA | 86 | ||||||

| AZERBAIJAN | 16 | ||||||

| BELARUS | 16 | ||||||

| BELGIUM | 79 | ||||||

| BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA | 56 | ||||||

| BULGARIA | 70 | ||||||

| CROATIA | 74 | ||||||

| CYPRUS | 79 | ||||||

| CZECH REPUBLIC | 90 | ||||||

| DENMARK | 88 | ||||||

| ESTONIA | 93 | ||||||

| FINLAND | 95 | ||||||

| FRANCE | 71 | ||||||

| GEORGIA | 62 | ||||||

| GERMANY | 76 | ||||||

| GREECE | 58 | ||||||

| HUNGARY | 50 | ||||||

| ICELAND | 87 | ||||||

| IRELAND | 88 | ||||||

| ITALY | 67 | ||||||

| KAZAKHSTAN | 27 | ||||||

| KOSOVO | 71 | ||||||

| KYRGYZSTAN | 40 | ||||||

| LATVIA | 89 | ||||||

| LIECHTENSTEIN | 93 | ||||||

| LITHUANIA | 91 | ||||||

| LUXEMBOURG | 90 | ||||||

| MALTA | 80 | ||||||

| MOLDOVA | 75 | ||||||

| MONACO | 91 | ||||||

| MONTENEGRO | 78 | ||||||

| NETHERLANDS | 82 | ||||||

| NORTH MACEDONIA | 71 | ||||||

| NORWAY | 94 | ||||||

| POLAND | 56 | ||||||

| PORTUGAL | 87 | ||||||

| ROMANIA | 73 | ||||||

| RUSSIA | 17 | ||||||

| SAN MARINO | 97 | ||||||

| SERBIA | 56 | ||||||

| SLOVAKIA | 80 | ||||||

| SLOVENIA | 70 | ||||||

| SPAIN | 69 | ||||||

| SWEDEN | 85 | ||||||

| SWITZERLAND | 85 | ||||||

| TAJIKISTAN | 12 | ||||||

| TURKEY | 27 | ||||||

| TURKMENISTAN | 8 | ||||||

| UKRAINE | 45 | ||||||

| UNITED KINGDOM | 58 | ||||||

| UZBEKISTAN | 18 |