Africa

Rating Overview

Civic space conditions in Africa South of the Sahara remain highly restrictive: 44 out of 50 countries and territories are rated as obstructed, repressed or closed, and over 80 per cent of people live in countries where civic space is repressed or closed. Civic space is open only in the island states of Cabo Verde and São Tomé e Príncipe, while Botswana, Mauritius, Namibia and Seychelles have narrowed civic space.

Sudan’s civic space rating has been downgraded from repressed to closed. Thousands of civilians have been killed since the outbreak of intense fighting between the Rapid support Forces (RSF) militia and Sudan’s armed forces in April 2023. Humanitarian workers, HRDs and journalists are being killed, attacked, detained and threatened. The war has weakened civil activity across all regions, whether controlled by the army or RSF, while multiple emergency orders have imposed curfews and restricted freedoms of expression, movement, opinion and peaceful assembly.

Burundi has also been downgraded from repressed to closed. Burundi’s June 2025 legislative and local elections took place in a deeply repressive political environment, marked by widespread restrictions on expression, media independence and political participation. Cases of extrajudicial killings, forced disappearances, attacks on and torture of political opponents and intolerance of all forms of criticism or dissent by HRDs, journalists and members of the public are continuing, while perpetrators such as the Imbonerakure militia – the ruling party’s youth league – and the National Intelligence Service enjoy state immunity.

Madagascar’s civic space rating has been downgraded from obstructed to repressed. Security forces regularly deploy excessive force and arbitrarily arrest protesters, and protests are regularly banned. Sustained youth-led anti-government protests erupted on 25 September 2025, initially over chronic electricity and water shortages, leading to the military seizing power in October 2025. In response to the protests, security forces used rubber bullets, stun grenades and teargas, and arrested, beat and threatened protesters. The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights estimated that at least 22 people were killed and over 100 injured in the first few days of protests and ensuing violence, with some killed by security forces. Protests against the Toliare mining project also saw the arrest and prosecution of activists and protesters. In recent years, restrictive laws such as the cybercrimes law have been used against environmental HRDs, social media users and whistleblowers.

Liberia’s civic space rating has been downgraded from narrowed to obstructed. This reflects attacks on freedoms of expression and peaceful assembly. Political party supporters and security forces have abducted, threatened and physically assaulted journalists. For example, ruling party youth members assaulted journalist Nyantee Togba, while Alex Seryea Yormie was abducted and tortured for broadcasting a government directive. Peaceful protests have been met with violence. A public protest in December 2024 escalated when law enforcement officers used teargas and allegedly live ammunition, leading to injuries and arrests. These incidents, including the temporary closure of a community radio station on the orders of a local official, point to a deteriorating environment where state and non-state actors increasingly restrict fundamental freedoms.

More positively, Gabon’s civic space rating has been upgraded from repressed to obstructed, reflecting improvements after the 2023 military coup that ended decades of repression by the former ruling Bongo family. Conditions for journalists have improved, allowing exiled reporters to return, and the transitional government maintained the timeline for presidential and legislative elections in 2025, which CSOs were able to monitor. A new bill aims to modernise the legal framework for CSOs. However, significant restrictions persist. The new electoral code barred opposition figures from running for president, and the law on political parties sets high membership thresholds, excluding smaller movements. The election enabled the leader of the coup to retain power. Journalists face summonses from security forces, and protests continue to be frequently banned or dispersed.

Mauritania’s civic space rating has also been upgraded from repressed to obstructed. This reflects several positive developments, including the government’s decision to join the Partnership for Information and Democracy, an intergovernmental initiative that seeks to address challenges posed by misinformation and the decline of independent journalism, and the regularisation of contracts for public service journalists, which enhances their professional stability. However, civic space remains restricted due to continued judicial harassment of activists and journalists. For instance, authorities arrested and convicted anti-slavery activist Ablaye Bâ for a video criticising the government’s migration policy and detained several journalists for their reporting. Law enforcement agencies also frequently use excessive force against protests, indicating that significant challenges to fundamental freedoms persist.

Senegal’s civic space rating has similarly been upgraded from repressed to obstructed. The upgrade follows a period of political transition, including peaceful early legislative elections in November 2024 and the adoption of a whistleblower protection law in August 2025. The new government has taken steps toward accountability for past abuses by offering financial assistance to the families of people killed in protests from 2021 to 2024 and revising a controversial amnesty law. Despite these positive steps, civic space remains restricted. Journalists continue to face arrests and judicial harassment for their reporting, including Simon Pierre Faye and Bachir Fofana, detained for allegedly spreading false news. Additionally, the government suspended 381 media outlets for non-compliance with regulations.

REGIONAL CIVIC SPACE TRENDS

Central Africa faced severe civic space restrictions, including suppression of dissent through censorship and judicial harassment, in 2015 amid political tensions and conflict. In eastern DRC, the M23 offensive led to censorship, internet shutdowns and targeting of journalists. Cameroon’s presidential election in October 2025 drove restrictions including the exclusion of the opposition and protest bans and crackdowns, resulting in arrests and deaths. In Gabon, despite the civic space upgrade,Journalists face summonses from security forces, and protests continue to be frequently banned or dispersed. The Republic of the Congo saw increased repression, including an opposition leader’s abduction and arrest of a lawyer supporting activists, and the exclusion of prominent civil society figures and CSOs from key political processes, further indicating declining freedoms before elections in 2026.

In 2025, countries in West Africa saw a deterioration of civic space, notably in countries under military rule. In Mali, the junta banned political parties, suppressed demonstrations and was alleged to be involved in disappearances of regime critics. Niger’s military government arrested journalists reporting on military matters, recriminalised online defamation and suspended international media outlets. In Guinea, security forces used lethal force against protests demanding a return to civilian rule, while activists faced abduction and torture. Beyond the Sahel, Nigeria arrested journalists for critical articles and protest coverage. Sierra Leone’s Counter-Terrorism Bill raised concerns among press freedom advocates for potentially criminalising journalism.

In the East and Horn of Africa, 2025 saw state repression through violent crackdowns on protests, the use of judicial tools to crush dissent . In Kenya in June and July 2025, protests commemorating the 2024 demonstrations against tax hikes faced lethal force, causing 65 deaths and injuring over 600 people. Authorities were accused of deploying armed gangs to attack protesters. In Uganda, authorities continued to arbitrarily arrest environmental activists opposing EACOP and opposition members. Somalia saw increased media repression, with 46 journalists arrested and media outlets raided between January and April 2025 alone, while security forces targeted journalists covering protests. Ethiopia’s government suspended the Ethiopian Health Professionals Association for supporting a strike and arrested journalists reporting on it.

In Tanzania, October 2025 elections characterised by the exclusion of opposition parties and the arrest and detention of opposition leader Tundu Lissu sparked deadly protests that the state met with a ruthless crackdown, leaving hundreds dead and over 300 facing prosecution in only the first few days.

A surge in state repression of protests was observed in Southern Africa, with authorities violently cracking down on protests and intensifying pressure on dissenting voices. In Mozambique, authorities met post-election demonstrations with a lethal response, resulting in hundreds of deaths and more than 4,200 arrests. In Angola, security forces violently suppressed protests against fuel price hikes, using excessive force, including live ammunition, tear gas and batons, leading to 30 fatalities and over 1,500 detained in the protests and the violence that ensued. Use of excessive force against protesters was also evident in South Africa, where a community leader, Vusi Banda, the chairperson of the Mondlo Township Civic Space Organisation, was assassinated after leading a service delivery protest.. Malawi witnessed state complicity in violence ahead of the 2025 general elections as masked assailants attacked peaceful protesters demanding electoral reform while security forces stood by. The region also saw judicial harassment of activists and journalists as a result of critical reporting and social media posts, including in Lesotho and Zambia.

CIVIC SPACE RESTRICTIONS

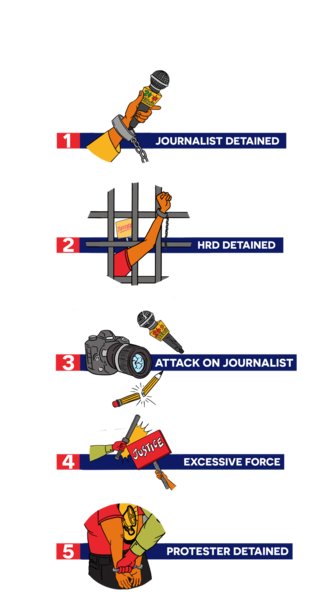

Detention of journalists and attacks on journalists

The detention of journalists was documented in at least 33 countries and territories in Africa South of the Sahara, with attacks on journalists in at least 16 countries. The detention of journalists was the top violation in Central, East and Horn and West Africa. Journalists were detained in at least 11 West African countries, nine in Southern Africa, seven in East and Horn of Africa and six in Central Africa. In countries including the DRC, Somalia and Somaliland, authorities continued to arrest journalists as a tactic to intimidate and silence them

Detention of HRDs

HRDs were detained in at least 25 countries in Africa South of the Sahara. Authorities commonly used this tactic to deter, intimidate and silence activists. HRDs working on democracy, environmental issues and labour rights were particularly targeted.

As in 2024, democracy activists were targeted in countries under military rule. In February 2025 in Guinea, unidentified gunmen abducted and tortured prominent civil society leader Abdoul Sacko, coordinator of a network calling for a return to constitutional order. He was found in a critical condition, having been beaten and abandoned in the bush 100 kilometres from Conakry. In Mali, unidentified people abducted civil society leader Aliou Badra Sacko in March 2025 during a meeting to oppose a new mobile money tax. He was reportedly detained in a secret state security prison for two months before his release. In Burkina Faso, armed personnel abducted democracy activist and lawyer Hermann Yaméogo in July 2025 shortly after he published a critique of President Traoré’s military regime on social media. Hermann was taken to the National Intelligence Agency before being released after 24 hours.

Somalia is steadily emerging as Africa’s top detainer of journalists, recording the highest number of journalists detained over the period covered by this report. Out of 180 detentions of journalists documented in Africa, 70 were from Somalia, the highest documented in a Country in sub-Saharan Africa during the period under consideration. Between January and April 2025 alone, authorities arrested 46 journalists, kidnapped two and raided several media outlets. Government ministries actively targeted critical reporting, leading many journalists to self-censor or go into exile. For instance, between 22 and 24 May 2025, security forces intensified their crackdown by arresting multiple reporters from Five Somali TV, Goobjoog Media, Himilo Somali TV, RNN TV, Shabelle TV, Somali Cable TV and SYL TV while they covered protests or engaged with the public in Mogadishu. In May 2025, National Intelligence and Security Agency agents raided the homes and media studio of journalists Mohamed Omar Baakaay and Bashir Ali Shire. During the raid, the agents blindfolded and arrested Bashir, detained Baakaay’s brother and confiscated equipment.

Despite government promises to decriminalise press offences in DRC, journalists face arrests under criminal provisions. For example, Glody Ndaya of L’Association Congolaise des Femmes Journalistes de la Presse Écrite (ACOFEPE) was arrested on 4 August 2025 for alleged defamation and taken to Makala Central Prison without summons. In M23-occupied areas of eastern DRC, journalists face abductions and intimidation. In February 2025, Congo River Alliance and M23 armed coalition forces in Goma abducted journalist Tuver Wundi, and in May they abducted Jérémie Wakahasha Bahati, both for critical reporting. On 5 August 2025, in Bukavu, South Kivu province, assailants abducted and killed journalist Fiston Wilondja Mukamba, former staff member of the Media monitoring Centre - a self regulation programme of the National Union of the Press of Congo (UNPC).

Authorities across Africa South of the Sahara have increasingly used cybercrime laws and other restrictive legislation to prosecute journalists and online critics. In Niger on 30 October 2025, authorities arrested six journalists and charged them with ‘complicity in distributing documents likely to disturb public order’, believed to be related to the circulation of a press briefing invitation, subsequently shared online by critics of new mandatory levies introduced by the military junta. In Kenya, police arrested blogger and teacher Albert Ojwang in June 2025 for a social media post allegedly spreading false information about a senior police official. He died in police custody the following day under suspicious circumstances, with an autopsy later revealing injuries consistent with blunt force trauma, sparking widespread protests.

In 2025, several journalists were attacked and detained while covering protests. In Madagascar, several journalists were injured by security forces while covering the youth-led anti-government protests. Security officers shot journalist Hardi Juvaniah Reny and struck photojournalist Alain Rakotondrainabe on the head even though both wore clearly visible press vests. In Togo, authorities detained French journalist Flore Monteau in June 2025 as she filmed police actions during anti-government protests, forcing her to delete her footage.

The safety of journalists and bloggers is at risk from state and non-state actors, including armed militia and supporters of political parties, particularly around elections.

In December 2024 in Mozambique, police shot and killed blogger and musician, Albino Sibia while he livestreamed a post-election protest. In Ghana, supporters of the New Patriotic Party assaulted JoyNews reporter Latif Iddrisu in May 2025 for covering the detention of a regional party chair. Journalists were also attacked or detained in countries including Ethiopia, Lesotho, Liberia, Malawi, Uganda and Zimbabwe.

Detention of HRDs

HRDs were detained in at least 25 countries in Africa South of the Sahara. Authorities commonly used this tactic to deter, intimidate and silence activists. HRDs working on democracy, environmental issues and labour rights were particularly targeted.

As in 2024, democracy activists were targeted in countries under military rule. In February 2025 in Guinea, unidentified gunmen abducted and tortured prominent civil society leader Abdoul Sacko, coordinator of a network calling for a return to constitutional order. He was found in a critical condition, having been beaten and abandoned in the bush 100 kilometres from Conakry. In Mali, unidentified people abducted civil society leader Aliou Badra Sacko in March 2025 during a meeting to oppose a new mobile money tax. He was reportedly detained in a secret state security prison for two months before his release. In Burkina Faso, armed personnel abducted democracy activist and lawyer Hermann Yaméogo in July 2025 shortly after he published a critique of President Traoré’s military regime on social media. Hermann was taken to the National Intelligence Agency before being released after 24 hours.

Authorities also arrested HRDs in connection with protests and strikes. In Kenya in June 2025, following protests over the killing of Albert Ojwang, police arrested three HRDs – Mark Amiani, Francis Mwangi and John Mulingwa Nzau – charging them with incitement to violence, despite civil society groups refuting the claims. In the Central African Republic, seven civil society activists were arrested in June 2025 during a vigil to commemorate students who died in a tragic explosion and to call for accountability.

HRDs have also been arrested for criticising authorities. In Mauritania, HRD Ahmed Ould Samba was sentenced to a year in prison in May 2025 for a Facebook post in which he accused the president of implementing ‘racist and corrupt’ policies. In Togo, activist and poet Honoré Sitsopé Sokpor was arrested in January 2025 and charged with ‘undermining the internal security of the state’ after publishing a poem online that condemned governmental oppression.

Lawyers have also been targeted. In the Republic of the Congo, lawyer Bob Kaben Massouka was arrested in July 2025, allegedly for supporting a group of young activists who were planning a peaceful protest against deteriorating socioeconomic conditions. He was charged with attempting to breach state security and criminal conspiracy. In Uganda, security officers assaulted and arrested human rights lawyer Eron Kiiza on 7 January 2025 as he tried to access a military courtroom where he was representing opposition leader Kizza Besigye. In Algeria, human rights lawyer Mounir Gharbi was sentenced in absentia to three years in prison on 16 February 2025, for ‘publicly displaying publications likely to harm the national interest’ after he posted Facebook comments.

Protesters detained and excessive force

Detention of protesters was documented in at least 19 countries in Africa South of the Sahara and the use of excessive force during protests in at least 20. As in previous years, many protests took place on a wide range of issues, including bad governance, corruption, the high cost of living and poor basic services. Authorities often detained protesters to try to break up protests and dissuade people from joining them.

Youth-led movements and protests against economic hardship have often been met with brutal state repression, leading to mass detentions and fatalities.

Kenya’s crackdown on youth-led protests commemorating the 2024 demonstrations against tax hikes, caused at least 65 deaths and injured over 600 people, and led to the arrest of more than 1,500 people between June and July 2025, with some facing terrorism charges. During one protest on 17 June 2025, at least one bystander was killed and 25 others hospitalised after police used live ammunition. Similarly, in Madagascar, security forces responded with disproportionate and lethal force. Following clashes on 9 October 2025, police arrested and referred for prosecution at least 28 protesters. Angola’s protests in July 2025 over fuel subsidy cuts were met with a violent police response. The crackdown on a three-day strike that escalated into larger protests saw police using excessive force, including live ammunition, tear gas and batons. At least 30 people were killed and 277 injured in the protests and violence, with over 1,500 people detained and hundreds facing summary trials. In The Gambia, during a peaceful protest against high internet data tariffs in August 2025, law enforcement officers arrested around 23 young protesters, including rapper Ali Cham, alias Killa Ace, and journalist Yusuf Taylor.

Elections and political tensions were another major trigger for protests, frequently met with state-sanctioned violence. Amid a crackdown on dissent in Togo, rapper and activist Aamron was arrested in May 2025 after releasing a video considered by authorities to be a veiled call for protests. He was detained at a psychiatric hospital for almost a month and reported being subjected to torture. In addition, authorities violently suppressed peaceful demonstrations in June 2025 against the high cost of living and constitutional changes allowing the president to extend his rule. Security forces and militia used disproportionate force, including batons and water cannon, and police arbitrarily arrested at least 81 protesters. In Cameroon, the period ahead of and following the October 2025 election was marked by repression. On 4 August 2025, security forces arrested at least 53 opposition supporters outside the Constitutional Council. On 26 October 2025, security forces used live ammunition and teargas to disperse protesters who defied a protest ban, leading to the killing of four people in Douala and the arrest of at least 105 people.

Protests by environmental activists and students also led to arrests and detentions. In Uganda, authorities arrested 15 environmental activists in November 2024 for protesting against the destruction of the Lwera wetland.In February 2025, another 11 environmentalists from the Students Against EACOP group were arrested during a protest at the EU mission and charged with ‘common nuisance’. In South Africa in February 2025, 15 students from the University of the Free State were arrested during protests over registration and funding issues.

Of concern

Transnational repression and the deepening crackdown on dissent across borders: Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda, Sudan and West Africa

In 2025, a deeply concerning trend of transnational repression intensified across Africa, signalling a collaborative effort by states to silence dissent beyond their borders. This escalating campaign, characterised by abductions, illegal renditions, judicial harassment and torture, has effectively erased safe havens for activists, journalists and opposition figures, creating a continent-wide climate of fear. Governments are increasingly using diplomatic ties and security agreements to hunt down dissidents, fundamentally violating international human rights laws, state sovereignty and the core principles of asylum and non-refoulement. This practice demonstrates a blatant disregard for due process and marks a strategic shift toward a more coordinated, regional approach to crushing dissent.

Central and West Africa are significant hotspots for this form of state-sponsored attack on dissent. The case of Burkinabe activist Alain Christophe Traoré, known as Alino Faso, offers one grim example. Arrested in Côte d’Ivoire on charges of ‘intelligence with agents of a foreign state’, he was later found dead by hanging in detention under highly suspicious circumstances. Such charges are often used to delegitimise and persecute exiled critics. Côte d’Ivoire was the site of another cross-border operation when Ivorian police arrested Beninese journalist Comlan Hugues Sossoukpè, who was living in exile, and promptly extradited him to Benin to face terrorism charges for his critical reporting. This incident highlights how governments exploit diplomatic ties to target activists and journalists who have fled persecution. It followed a similar case in Benin in which another Beninese critic, digital activist Steve Amoussou, was abducted from exile in Lomé, Togo in August 2024 and sentenced to two years in prison for ‘politically motivated insult’ and ‘spreading false information’ linked to a Facebook page critical of the government.

The East and Horn of Africa witnessed some of the most blatant acts of transnational repression. A coordinated operation between Kenyan and Ugandan authorities led to the abduction of prominent Ugandan opposition leader Kizza Besigye from Nairobi. He was illegally rendered to Uganda to face charges in a military court, a move that circumvents civilian legal protections and demonstrates the misuse of state security apparatus to neutralise political opponents. In a shocking display of regional impunity, suspected Tanzanian military agents abducted, tortured and sexually assaulted Kenyan activist Boniface Mwangi and Ugandan journalist Agather Atuhaire while they were in Dar es Salaam to observe Tundu Lissu’s trial. The Kenyan government’s actions were also scrutinised following the unlawful deportation to Uganda of Martin Mavenjina, a senior legal advisor at the Kenya Human Rights Commission, in what was widely condemned as a politically motivated move to silence a key civil society voice. These events collectively paint a picture of an alarming authoritarian alliance.

In Sudan, the government has extended its crackdown on dissent beyond its borders, targeting anti-war figures and political opponents living abroad. A significant instance of this transnational repression occurred in April 2024, when the acting Attorney General filed serious criminal charges against the former civilian Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and other leaders of the Taqaddum political coalition, many of whom are not in Sudan. The charges included grave accusations such as crimes against humanity, ‘inciting war against the state’ and undermining constitutional order, with some carrying the death penalty. This legal persecution of prominent figures in exile is a clear strategy to silence opposition and those advocating for an end to the conflict from outside Sudan. Other journalists, lawyers and WHRDs outside Sudan have reported receiving threats, indicating a broader campaign to intimidate the Sudanese diaspora.

| COUNTRY | SCORES 2025 | 2024 | 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 |

| ANGOLA | 24 | |||||||

| BENIN | 49 | |||||||

| BOTSWANA | 72 | |||||||

| BURKINA FASO | 25 | |||||||

| BURUNDI | 12 | |||||||

| CAMEROON | 23 | |||||||

| CAPE VERDE | 88 | |||||||

| CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC | 35 | |||||||

| CHAD | 31 | |||||||

| COMOROS | 56 | |||||||

| CÔTE D'IVOIRE | 53 | |||||||

| DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO | 26 | |||||||

| DJIBOUTI | 12 | |||||||

| EQUATORIAL GUINEA | 15 | |||||||

| ERITREA | 4 | |||||||

| ESWATINI | 15 | |||||||

| ETHIOPIA | 20 | |||||||

| GABON | 54 | |||||||

| GAMBIA | 47 | |||||||

| GHANA | 60 | |||||||

| GUINEA | 29 | |||||||

| GUINEA BISSAU | 44 | |||||||

| KENYA | 31 | |||||||

| LESOTHO | 60 | |||||||

| LIBERIA | 55 | |||||||

| MADAGASCAR | 35 | |||||||

| MALAWI | 50 | |||||||

| MALI | 26 | |||||||

| MAURITANIA | 44 | |||||||

| MAURITIUS | 77 | |||||||

| MOZAMBIQUE | 27 | |||||||

| NAMIBIA | 80 | |||||||

| NIGER | 32 | |||||||

| NIGERIA | 36 | |||||||

| REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO | 28 | |||||||

| RWANDA | 25 | |||||||

| SAO TOME AND PRINCIPE | 88 | |||||||

| SENEGAL | 47 | |||||||

| SEYCHELLES | 80 | |||||||

| SIERRA LEONE | 44 | |||||||

| SOMALIA | 28 | |||||||

| SOMALILAND | 34 | |||||||

| SOUTH AFRICA | 61 | |||||||

| SOUTH SUDAN | 21 | |||||||

| SUDAN | 9 | |||||||

| TANZANIA | 26 | |||||||

| TOGO | 29 | |||||||

| UGANDA | 28 | |||||||

| ZAMBIA | 53 | |||||||

| ZIMBABWE | 28 |

*Covering countries south of the Sahara.