Europe and Central Asia

Rating Overview

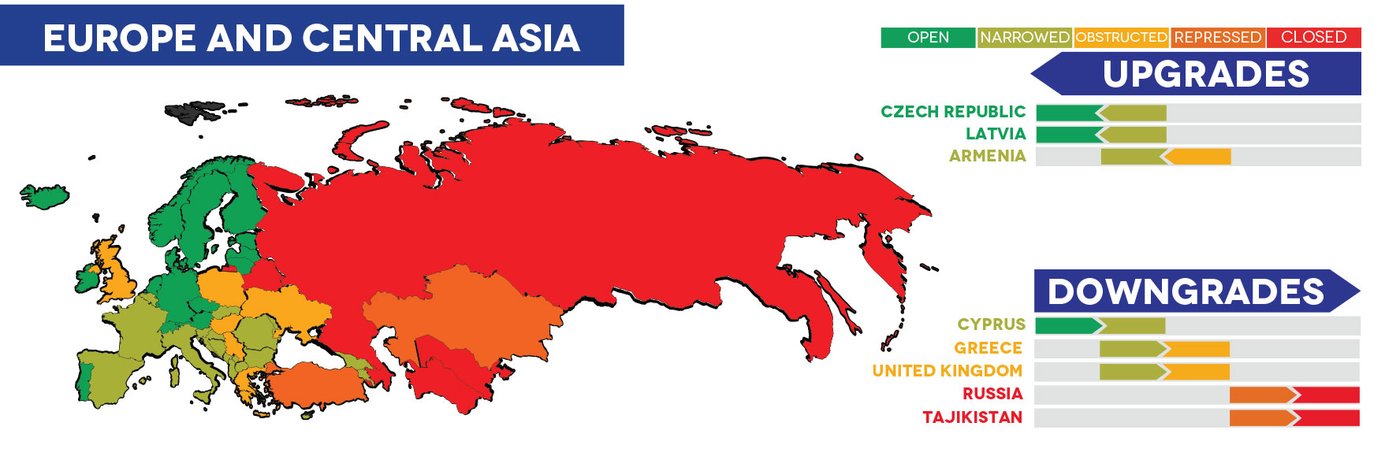

Civic space continues to come under attack in the Europe and Central Asia region. Of the region’s 54 countries, civic space is rated as open in 20, narrowed in 19, obstructed in seven, repressed in two and closed in six.

In 2022, democratic backsliding continued in Europe with several authoritarian leaders, such as Hungary’s Viktor Orban and Serbia’s Aleksandar Vučić, further consolidating their power, bringing increased concerns for civic freedoms. Far-right leaders also made significant gains, including in Italy and Sweden, while long-established democracies such as the UK saw further restrictions on civic freedoms. Russia’s war on Ukraine had significant political, economic and social implications for the region, with civil society both in and outside the conflict area mobilising to support people fleeing the war.

Central Asia saw several serious crises where the authorities forcibly cracked down on mass protests and ensuing unrest inKazakhstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, resulting in significant loss of life and injuries. Across Central Asia people faced ongoing persecution for criticising the authorities and standing up for justice, human rights and the rule of law.

Overall country ratings in the region have worsened. The ratings of four European countries have been downgraded: Cyprus, Greece, Russia and the UK. Two of these countries are European Union (EU) member states. The situation in Central Asia has also worsened, with Tajikistan experiencing a particularly severe decline in civic space, resulting in a rating downgrade.

Cyprus has been downgraded from ‘’open’’ to ‘’narrowed’’. Concerns include the ongoing legal battle by the Action for Support, Equality and Antiracism (KISA), which was removed from the registry of associations in 2020 and since then is operating under significant restrictions. The organisation continues to legally challenge its dissolution and believes that this restriction is part of the government’s widening crackdown on those working to protect refugees and asylum seeker rights. Funding for civil society is a challenge, with national banks treating NGO bank accounts as high risk which has resulted in CSOs facing additional administrative and financial burdens.

Concerns over the repeated targeting of civil society working with refugees and asylum seekers, disproportionate responses to protests and continuous legal harassment and surveillance of journalists has prompted ratings change from “narrowed” to “obstructed” in Greece. Several CSOs and human rights defenders (HRDs) working on migrant rights have been targeted. Four CSOs who have challenged the government in several cases of push backs, were put under investigation for ‘’possible links to smuggling’’, while activist Panayote Dimitras is accused of “setting up a criminal organisation with the purpose of facilitating the illegal entry and stay in Greece of third-country nationals''. In addition, Greek journalist Thanasis Koukakis and several others, including opposition politicians, were subject to surveillance via Predator spyware.

In Russia, the government’s crackdown on civic space further intensified since it launched its full-scale war on Ukraine, prompting a rating change from repressed to closed. Nationwide anti-war protests have been brutally repressed, with over 19,500 people detained since February 2022. Journalists reporting on protests have faced brutal attacks. Several independent media outlets have shut down as a result of ongoing pressure from the authorities, while a recently passed foreign agents law is likely to be used to further stifle civil society. Russia’s downgrade follows its addition to the CIVICUS Monitor Watchlist in March 2022.

Civic space deteriorated dramatically in Tajikistan during the year, prompting a rating change from repressed to closed. The authorities cracked down on mass protests in the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region (GBAO), which saw people taking to the streets of the city of Khorog to demand the resignation of the regional leader and justice for a young man killed during a police operation. In response, the authorities carried out special security operations in the region, which brought allegations of excessive force, arbitrary detentions, torture and extrajudicial killings of detainees. Since then the authorities have failed to impartially and effectively investigate reported human rights violations. As part of the crackdown, around 20 human rights activists and journalists critical of the government’s policies in the GBAO were detained and prosecuted, with others facing growing intimidation and harassment. The space for independent media remains limited, with the arbitrary blocking of independent news sites and social media networks.

A significant deterioration in civic freedoms in the UK, particularly the right to freedom of peaceful assembly, has led to the country being downgraded from narrowed to obstructed.

However, a positive shift for civil society came in the Czech Republic under the government of Prime Minister Petr Fiala, prompting a rating change from narrowed to open. The new government has put forward a draft legislative proposal to strengthen the editorial independence of Czech Television. Journalists, however, continue to face harassment from the former prime minister. Latvia’s civic space rating has also improved to open. Civil society reports that there is an overall favourable environment, with CSOs being involved in decision-making, and an online portal that enables engagement in consultation processes. Civic space in Armenia has shown improvements, resulting in a rating change from obstructed to narrowed, with indications of enhanced collaboration between the state and CSOs in policy-making processes and increased transparency of allocation of state funds to CSOs. In June 2022, amendments to the Criminal Code saw the decriminalisation of the offence of grave insult.

Civic Space Restrictions

In Europe and Central Asia, the most common violations of civic freedoms documented in 2022 were harassment, intimidation, detention of protesters, attacks on journalists and the passing of restrictive laws. Over the past five years, harassment has been one of the most common tactics used in the region to crack down on civil society.

Harassment and intimidation

In 2022, harassment was the most common civic space violation, documented in at least 36 countries in the region, while intimidation was documented in at least 25 countries. The groups most commonly targeted in the region were women, LGBTQI+ groups and labour rights groups.

In many countries harassment and intimidation takes place online and extends to offline spaces, and at times can lead to physical attacks on activists and journalists. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, LGBTQI+ activists faced online harassment before and after holding a Pride march, including from high-level politicians. In North Macedonia, Bekim Asani, president of the LGBTQI+ United CSO, was subject to threats and insults, leading up to a physical attack that took place in Strumica at a public event to promote the organisation. Activist Dragan Dmitrović reported that police officers threatened him with death shortly before he was forced to sign a false confession incriminating three other activists for protest in Serbia after violence.

Women are disproportionately targeted through gendered intimidation and harassment. Several cases have been documented against women journalists in the region, including in Bosnia and Herzegovina,France, Italy, Montenegro, Romania and Turkey.

In Romania, journalist Emilia Sercan, who has faced threats since 2016, filed a police report after being threatened online and discovering that old private photographs had been stolen from her hard drive and put on porn sites. The screenshots, which she filed with the police report, were then leaked and widely shared on the internet.

Smear campaigns are another way in which harassment takes place. In Hungary in October 2022, the government-financed think tank Centre for Fundamental Rights (Alapjogokért Központ) accused Amnesty International of promoting sex-change surgeries in schools because the group promotes a project, ‘Inclusive Spaces’, which aims to provide information to teachers and students about LGBTQI+ people and their rights.

In some cases the criminal justice system is used as a tool to harass activists, including in Poland, where pro-abortion activist Justyna Wydrzyńska, from the Aborcyjny Dream Team group faces up to three years in prison for aiding and abetting a pregnancy termination. In 2020 Wydrzyńska sent abortion pills she had at home to a woman who had contacted her who was in an abusive relationship with an unwanted pregnancy. In Turkey, We Will Stop Femicide Platform, a leading women’s CSO, is facing prosecution for ‘acting against the law and against morality’.

Legal intimidation and harassment through Strategic Litigation Against Public Participation (SLAPPs) lawsuits filed by both state and private actors were frequently documented in the region, including in Croatia, Greece and Lithuania. These cases are often lengthy and expensive and serve to drain the resources of CSOs and media outlets in an attempt to silence critical voices. In Serbia, the Crime and Corruption Research Network (KRIK), an investigative portal, was found guilty in a SLAPP case initiated by Bratislav Gašić, former head of the Security Intelligence Agency and now Minister of Internal Affairs. The lawsuit came after KRIK reported on a public trial by quoting a wiretapped conversation used as evidence against a criminal group, which exposed the group's ties with Gašić.

Palestinian activists in Austria and Germany have also faced legal harassment. In one case, widely condemned by several UN Special Rapporteurs, a member of Boycott Divestment Sanctions Austria was found guilty of defamation and fined €3,500 (approx. US$3,700) plus legal fees after the municipality of Vienna filed a case over a Facebook post that it argued ‘incites hatred against Israeli people’. The post contained a picture of a poster stating ‘Visit Apartheid’ that was stuck on an official city of Vienna billboard.

Intimidation and harassment are frequently used in Central Asia to repress government critics. In addition to suppressing dissent at home, the authorities in Turkmenistan continued to target activists based abroad, particularly in Turkey, putting pressure on them both directly and indirectly through their relatives in Turkmenistan. Increasing intimidation and harassment of journalists, bloggers, lawyers, civil society activists and other critical voices was also documented in Kyrgyzstan. In one high-profile case, more than 20 activists were arrested and charged with organising riots after publicly opposing a controversial government-negotiated border agreement with Uzbekistan. The authorities in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan targeted journalists and activists in crackdowns launched in response to mass protests that were suppressed. In Kazakhstan, at least 30 activists, including Zhanbolat Mamai, leader of the opposition Democratic Party, were charged with rioting and other offences related to predominantly peaceful mass protests for social and political change in January 2022, despite the lack of any credible evidence to support charges.

Detention of protesters and attacks on journalists

The detention of protesters was documented in at least 29 countries in the region. Protests took place on several issues including environmental rights, LGBTQI+ rights, labour rights, socio-economic rights and democracy. In addition, physical attacks on journalists were documented in at least 24 countries, in many cases during protests.

Protests by environmental groups involving civil disobedience, calling on governments and industries to respond to the climate crisis, resulted in detentions in countries including Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, theNetherlands, Norway, Portugal,Spain, Sweden and the UK. In one example in Serbia, environmental activists protested against the planned construction of a bridge in Novi Sad, claiming it will devastate the city’s last green oasis. They were met with a strong police presence, with several protesters detained. They also suffered serious injuries.

Democracy protesters in Belarus and Russia continue to face serious repression. Following Vladimir Putin’s announcement of a ‘partial mobilisation’ of reservists to join the war against Ukraine, activists immediately called for protests. More than 2,240 people were arrested during protests between 21 and 25 September 2022.

In some cases, the authorities issued bans on protests, which often failed to deter people from protesting but resulted in repression. In Turkey, the authorities prohibited the annual Pride march in Istanbul on the grounds of preventing crime and maintaining peace and security. Despite this, thousands took the streets, resulting in the overnight detention of 373 people, including LGBTQI+ activists and journalists. In Azerbaijan, the authorities refused to authorise a protest by Tofig Yagublu, a member of the National Council of Democratic Forces coordination centre and the Musavat Party, calling for continued closure of land borders. The protest proceeded despite the refusal, with police responding by dispersing the crowd and detaining over 40 protesters.

In Central Asia, several mass protests were brutally repressed. In Kazakhstan, the authorities used excessive and lethal force during the January 2022 protests, in what became known as ‘Bloody January’, in which over 230 people were killed, several thousand injured and around 10,000 detained. In Uzbekistan, proposed constitutional amendments, which would have deprived the Republic of Karakalpakstan of its autonomous status and its constitutional right to secede, triggered mass protests that the authorities responded to with excessive force, arbitrary detentions and torture and ill-treatment of detainees. While official figures indicate that 21 people died and 270 were left needing medical assistance, civil society believes the true number of casualties might be higher.

While protests rarely take place in Turkmenistan, the authorities are quick to quell any attempts to mobilise. In Kyrgyzstan, the authorities detained people who peacefully gathered despite a ban on protests against Russia’s war on Ukraine.

Journalists are frequently attacked in the region while covering protests. During anti-war protests in Russia, women journalists Elizaveta Kirpanova of Novaya Gazeta and Vera Ryabitskaya of The Insider were pushed to the ground and hit with truncheons while reporting from Moscow and St Petersburg respectively. Women journalists have also come under attack in Italy, Montenegro,Spain andTurkey. In Kazakhstan, media workers were obstructed and attacked by security forces and non-state actors when covering the ‘Bloody January’ protests. For example, Orda.kz journalist Bek Baytas was hit by a stun grenade and injured in the face, but managed to escape before the grenade exploded.

In several cases far-right groups have perpetrated attacks. In addition, violence against journalists has also frequently been documented in protests against pandemic measures. In Germany, during a demonstration against the rise in energy and food prices organised by the far-right Alternative for Germany party on 8 October 2022, freelance journalist Armilla Brandt was physically attacked and protesters hurled sexualised threats at her. A worrying number of similar attacks against journalists perpetrated by far-right militants and the Querdenker pandemic conspiracy theorist movement were reported in Germany.

In Ukraine, 15 journalists have so far been killed since the start of the war, while others have been detained by Russian occupation troops and subjected to physical and mental pressure.

Country of concern: The UK

For the last three years, civic space in the UK has been in decline. In September 2021, the country was placed on the CIVICUS Monitor Watchlist to signal a rapid decline in civic freedoms. Since then, the situation has continued to deteriorate, with the government introducing a range of restrictive laws, particularly on protest. This has led to a rating change from narrow to obstructed.

Two pieces of legislation in particular seriously undermine the right to protest and give extensive new powers to the police and Home Secretary.

The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act came into effect in April 2022 despite wide opposition. The Act gives police unprecedented powers to restrict protests on the basis of noise and introduces further restrictions on processions and static assemblies. Further to this, the Public Order Bill, currently making its way through parliament, gives police additional powers to restrict protests. Some of the concerning measures in the Bill include Serious Disruption Prevention Orders, which could ban named people from participating in protests, and the introduction of protest-related stop-and-search powers. Five UN Special Rapporteurs have said that the Bill ‘could result in undue and grave restrictions’ on civil liberties if not seriously amended.

Existing powers have already permitted the authorities to unduly restrict the right to protest by detaining protesters and preventing demonstrations, particularly on issues such as climate change and the environment and racial justice. Legal observers at protests have reported experiencing high levels of harassment, intimidation and aggression by police. Netpol, a police monitoring network, estimated that at the end of 2022, at least 54 people were in prison for taking part in protests. This included protesters from ‘Kill the Bill’ demonstrations against the new police laws, Black Lives Matter protesters, people from environmental groups and pro-Palestinian activists. Several journalists were also arrested while covering protests by the Just Stop Oil activist group, after which an independent panel said ‘police powers were not used appropriately’. After civil society complaints of disproportionately heavy policing towards Black Lives Matter campaigners and restrictions imposed on earlier demonstrations, in September 2022 two Black Lives Matter activists were found guilty of 'violent disorder' following a jury trial and sentenced to two years and five months and two years and ten months in jail respectively. Such prosecutions, relying on the discredited principle of ‘joint enterprise’ to sentence multiple Black activists to periods of imprisonment, reflect broader institutional racism within the criminal justice system in the UK.

The decline in protest rights is taking place within a broader context of restrictions that are delegitimising civil society action. This includes limiting people’s ability to strike through the Minimum Service Levels Bill, seek justice through the courts through the Judicial Review and Courts Act, participate in elections through the Elections Act and pursue political activities or journalism through the National Security Bill. Throughout the year the government has repeatedly raised the notion of repealing the Human Rights Act by bringing in the ‘Bill of Rights’ Bill which, although currently deprioritised, has led to wider discussions about the UK’s withdrawal from the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR). This would have significant implications for access to justice. The Human Rights Act and the ECHR protect everyone from human rights abuses, from domestic abuse survivors to journalists to people being secretly monitored by the state. The current rhetoric focuses on removing rights from already excluded groups. For example, in June the ECHR halted the government's attempts to expel asylum seekers to Rwanda, after the government sought to push ahead with the deportation despite the country being deemed unsafe. Any repeal of the Human Rights Act or withdrawal from the ECHR will have significant, far-reaching consequences.

Amidst these developments, increased critical sentiment among some politicians and sections of the media that support the ruling party towards civil society campaigning has increased over the last year. Some ministers and members of parliament have smeared and publicly vilified civil society, particularly civil society working on climate change, anti-racism and migrants’ and refugee’s rights. The former Home Secretary referred to protesters as ‘vandals and thugs’. Ministers have also been criticised for making misleading and vilifying public statements about legal professionals, as has former prime minister Boris Johnson, who suggested that lawyers working on behalf of migrants were ‘abetting the work of criminal gangs’. The current Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, has previously made comments that left-wing agitators are bulldozing British rights’.

| COUNTRY | SCORES 2022 | RATING 2022 | RATING 2021 | RATING 2020 | RATING 2019 | RATING 2018 |

| ALBANIA | 67 | |||||

| ANDORRA | 84 | |||||

| ARMENIA | 70 | |||||

| AUSTRIA | 83 | |||||

| AZERBAIJAN | 20 | |||||

| BELARUS | 16 | |||||

| BELGIUM | 80 | |||||

| BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA | 64 | |||||

| BULGARIA | 71 | |||||

| CROATIA | 72 | |||||

| CYPRUS | 72 | |||||

| CZECH REPUBLIC | 86 | |||||

| DENMARK | 90 | |||||

| ESTONIA | 94 | |||||

| FINLAND | 91 | |||||

| FRANCE | 74 | |||||

| GEORGIA | 68 | |||||

| GERMANY | 86 | |||||

| GREECE | 52 | |||||

| HUNGARY | 49 | |||||

| ICELAND | 87 | |||||

| IRELAND | 84 | |||||

| ITALY | 76 | |||||

| KAZAKHSTAN | 35 | |||||

| KOSOVO | 72 | |||||

| KYRGYZSTAN | 45 | |||||

| LATVIA | 89 | |||||

| LIECHTENSTEIN | 93 | |||||

| LITHUANIA | 85 | |||||

| LUXEMBOURG | 84 | |||||

| MALTA | 74 | |||||

| MOLDOVA | 79 | |||||

| MONACO | 94 | |||||

| MONTENEGRO | 71 | |||||

| NETHERLANDS | 87 | |||||

| NORTH MACEDONIA | 73 | |||||

| NORWAY | 95 | |||||

| POLAND | 51 | |||||

| PORTUGAL | 82 | |||||

| ROMANIA | 64 | |||||

| RUSSIA | 17 | |||||

| SAN MARINO | 94 | |||||

| SERBIA | 50 | |||||

| SLOVAKIA | 77 | |||||

| SLOVENIA | 63 | |||||

| SPAIN | 74 | |||||

| SWEDEN | 87 | |||||

| SWITZERLAND | 85 | |||||

| TAJIKISTAN | 19 | |||||

| TURKEY | 29 | |||||

| TURKMENISTAN | 10 | |||||

| UKRAINE | 45 | |||||

| UNITED KINGDOM | 60 | |||||

| UZBEKISTAN | 20 |