Tactics of Repression

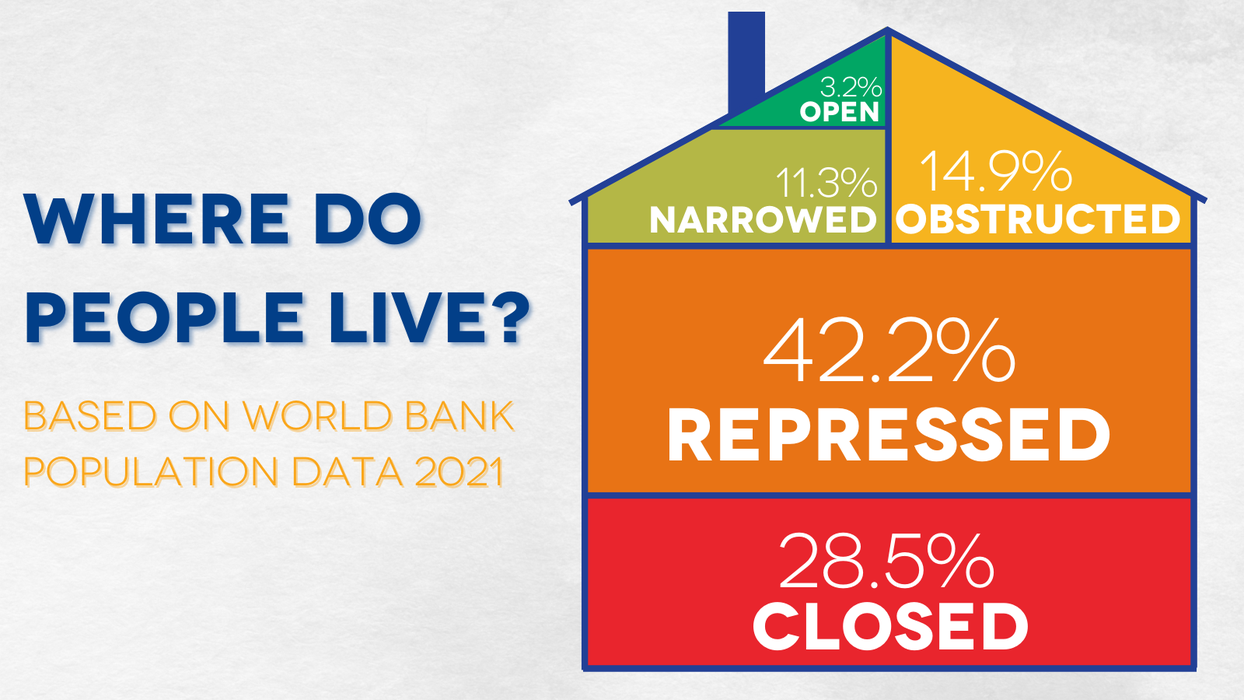

Civil society activists and HRDs hold governments accountable for their actions and demand compliance with human rights commitments according to international standards. These efforts come with great risk. In many countries, the exercise of fundamental freedoms of association, peaceful assembly and expression can lead to dire consequences. 2022 was marked by a serious decline in civic space, with more people living in countries with closed civic space than ever. Twenty-eight per cent of the world’s population – approximately two billion people – are subject to extreme levels of repression.

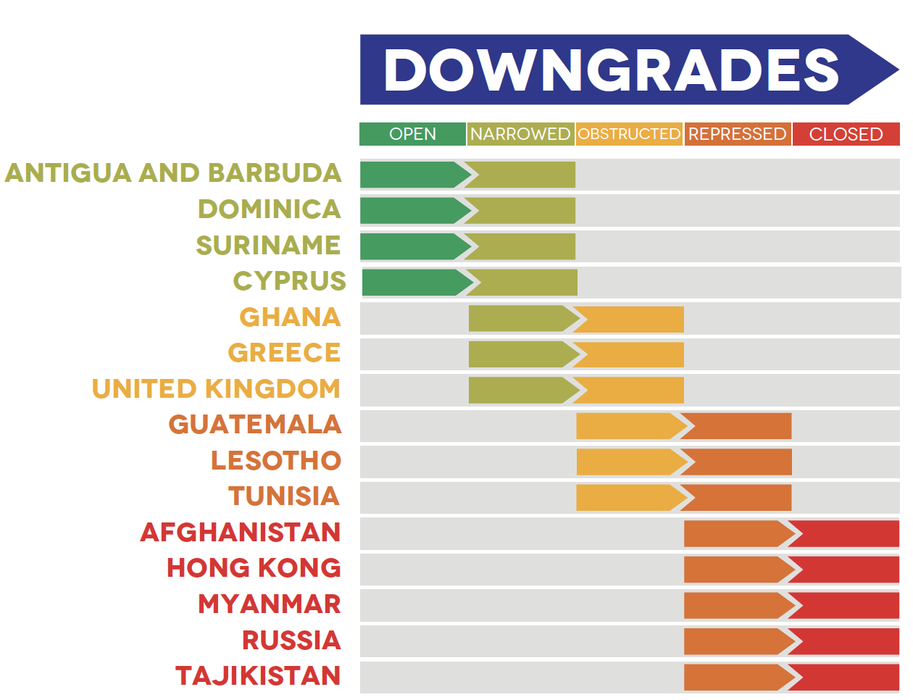

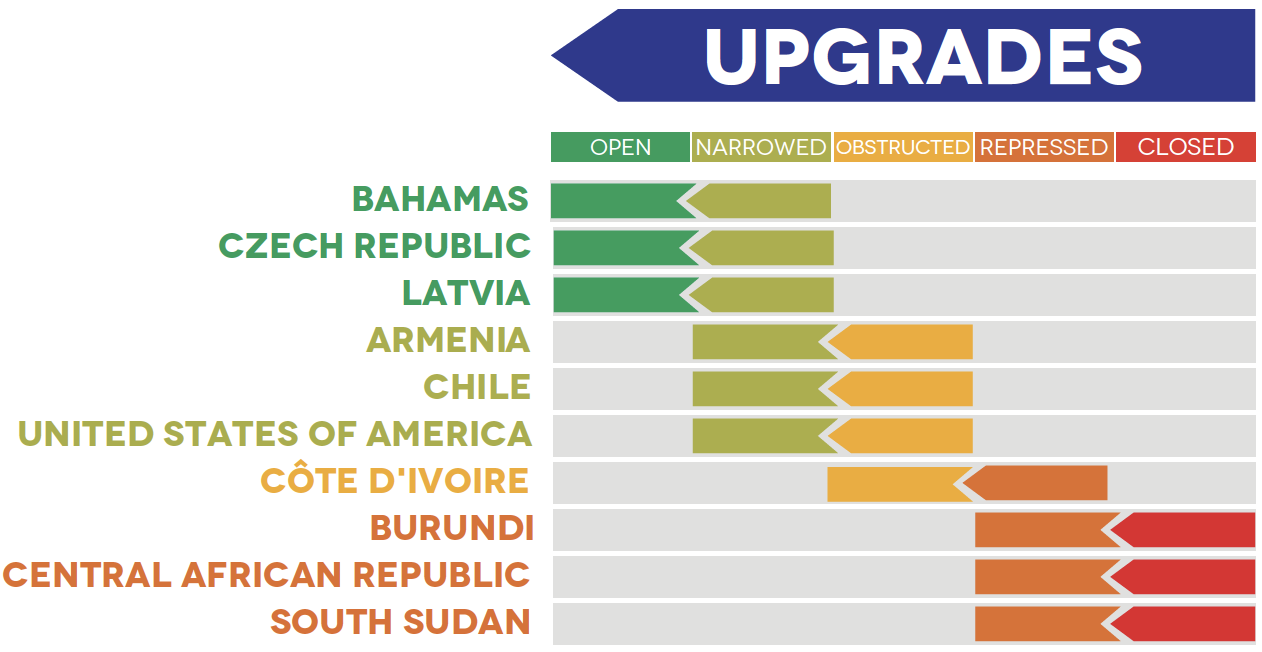

Since the previous edition of this report, published in December 2021, the story has been one of further regression: civic space ratings have changed for 25 countries in the last year, worsening in 15 countries and improving in only 10*.

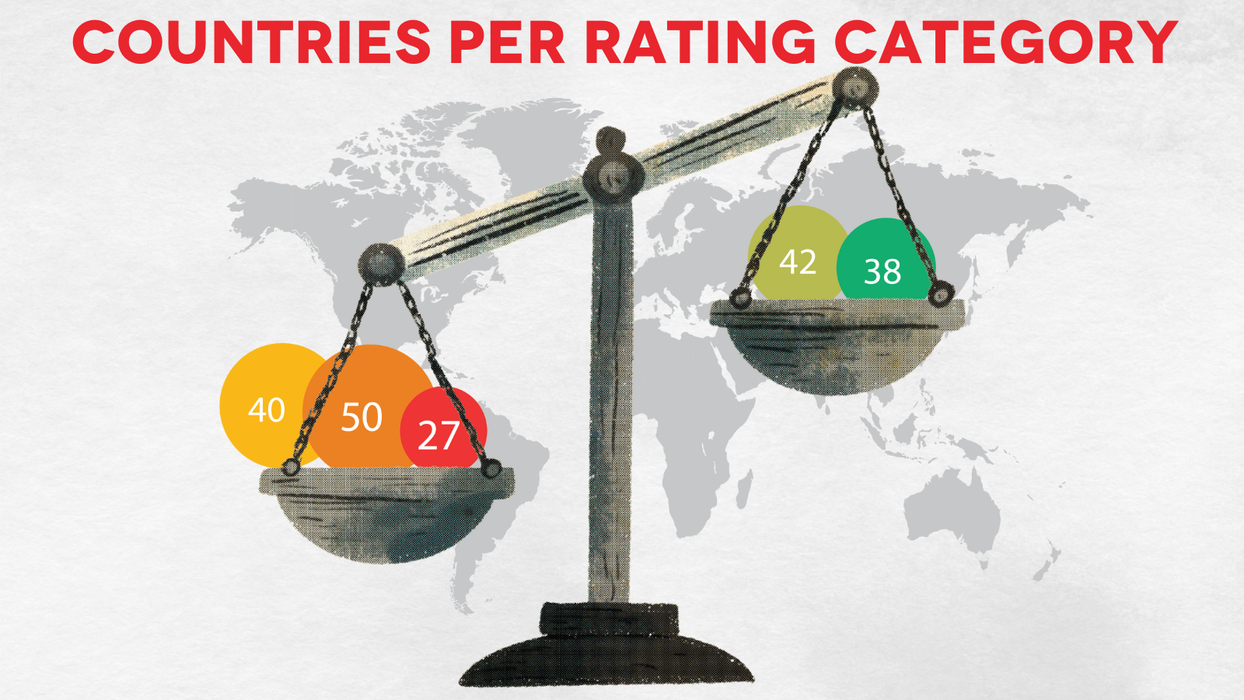

The latest update of CIVICUS Monitor country ratings in March 2023 indicates that civil society faces an increasingly hostile environment. There are 27 countries or territories with closed civic space, 50 with repressed civic space, and 40 with obstructed civic space, meaning that 117 of 197 countries and territories are experiencing severe restrictions on fundamental freedoms. In comparison, 42 countries have narrowed civic space, and just 38 have an open rating.

The civic space crisis: a story foretold

The further regression of civic space conditions should not come as a surprise. In many countries, the increased level of restrictions on civil society has been the subject of warnings by activists and human rights watchdogs. The CIVICUS Monitor Watchlist, which highlights serious civic space concerns, has in recent years included most of the countries now being downgraded.

Five countries are downgraded to the worst category: Afghanistan, Hong Kong, Myanmar, Russia and Tajikistan are now rated as closed. Guatemala, Lesotho and Tunisia are downgraded to the repressed rating as conditions for civil society continue to worsen.

In addition, three countries drop down into the obstructed category: Ghana, Greece and the UK. Very few countries are rated as open and narrowed in Africa, and there is now one less with the downgrading of Ghana, where attacks against journalists, including physical attacks, arbitrary detentions and prosecutions, have increased in recent years.

Although Europe has the most countries rated as open, ratings changes highlight that no region is immune to state restriction of civic freedoms, with Greece and the UK now downgraded to the obstructed rating and Cyprus to narrowed rating. Over the past five years, eight European countries have seen their ratings downgraded due to deteriorating civic space conditions.

From marginal improvement to systemic change?

Although 10 countries have upgraded ratings in 2022, there is still much room for improvement. Burundi, the Central African Republic (CAR) and South Sudan move from the closed to the repressed category, which means that people living in these countries continue to face severe restrictions when speaking out or protesting; while some improvements have been noted, structural and systemic changes that could foster an enabling environment for civil society are still pending. Côte d’Ivoire also sees a rating upgrade from the repressed to the obstructed category, as fewer civic space violations were documented compared with 2020, during which civic space violations rose due to a highly contested and controversial electoral period.

Two countries in the Americas – Chile and the USA – also saw an improvement, moving from obstructed to narrowed civic space ratings with changes in political leadership opening a path for better protection of civic space.

In Europe, the Czech Republic and Latvia improved their rating from narrowed to open. Under the government of Prime Minister Petr Fiala a few positive changes have been documented. For example, the draft legislative proposal to strengthen the editorial independence of Czech Television. In Latvia, civil society reports an overall favourable environment, with CSOs being more involved in decision-making. Civic space in Armenia has shown improvements, particularly after the 2018 revolution, resulting in a rating change from obstructed to narrowed.

Any steps taken towards opening civic space are welcomed, but in most of these countries changes in policies and practices still need to be made to enable the full enjoyment and protection of civic freedoms. To achieve more open and democratic societies and move from small improvements towards systematic change, civil society must be free to operate and hold governments accountable.

Tactics of repression

Repeated targeting of civil society activists: harassment as a tool to stifle dissent

During 2022, the most common violation documented by the CIVICUS Monitor was the harassment of civil society activists and journalists. Over the past five years, the use of this tactic by states, and increasingly by non-state actors, has spread across the world to deter activists and civil society organisations (CSOs) from continuing their work and silence dissent and criticism. The number of countries where harassment against activists was documented increased from 65 in 2018 to 106 in 2022. This tactic is widely used in all countries, with ratings from open to closed, meaning that it has become a widespread tool, regardless of the level of rights protection that may exist in a country.

Although harassment is perceived as a relatively subtle form of repression and, in some instances, is used intentionally to leave little trace and ensure impunity, it is highly effective in deterring HRDs from their work and can strategically restrict the space for CSOs. Cuba is one country where this tactic is notoriously used, with HRDs and journalists systematically harassed. For instance, during September and November 2022, several HRDs reported various forms of harassment to force them to shut down their organisations or resign from their positions. Cubalex director Laritza Diversent’s family was harassed by state security agents who reportedly told her mother that she would only receive support with housing and medical care issues if her daughter resigned from the organisation.

Another country with closed civic space where this tactic was documented was Vietnam, where hundreds of activists and dissidents are subjected to indefinite house arrests and travel bans without prior notice, along with other forms of harassment. In Uzbekistan, bloggers are pressured and harassed by police, who search their houses and send threatening messages if they write critical articles. In addition, police and security agencies use this tactic to deter journalists from reporting on sensitive and controversial issues. In Azerbaijan, a journalist was summoned by the police after posting articles about the army. Similarly, in Timor-Leste, two journalists were summoned by the police after publishing two reports on a minister’s request to dismiss the Director of Internal Intelligence at the National Intelligence Service. In Argentina, a journalist received a court order that she should stop publicly speaking about a child abuse case, and though she had complied, the authorities ordered a raid on her house and seized her work materials. Beyond the direct harassment of journalists, Bangladesh authorities detained family members of journalists reporting from abroad.

This tactic is also widespread in countries with higher levels of rights protection. In Portugal and Sweden, for example, journalists face periodic harassment, and in Germany, journalists can face harassment from the state and other sources when reporting on protests.

Women are a particular target of gendered forms of harassment that often targets their families as well. Activists from the Serbian organisation Women for Peace have been the target of threats and cyberattacks after criticising the allocation of city budget funds to a convicted abuser for the opening of a new centre to combat domestic violence. One of the threats explicitly mentioned one of the activists’ daughters and grandchildren. Women in political positions also face sexism and online harassment in Montenegro.

Harassment can in some instances pave the way for militant groups to take violent action. In Lebanon, for example, Dalia Ahmad, the presenter of Al-Jadeed TV’s Fashit Kheleq show, and actress Joanna Karaky were victims of social media harassment after a satirical segment was aired on the show in response to the killing of an Irish peacekeeping soldier in Lebanon. Militants threw a petrol bomb at the TV channel’s headquarters and unknown assailants opened fire on the building.

Harassment affects civil society activists and journalists in terms of their physical and digital security and mental health. Many continue to work, however, despite the effects it has on their lives and the lives of their families.

Right to protest undermined: detention as a tactic to prevent and disrupt protests

CIVICUS Monitor findings show an ongoing crackdown on freedom of peaceful assembly over the past five years. These restrictions peaked during the COVID-19 pandemic: in 2020 and 2021, the detention of protesters was the number one civic space violation documented by the CIVICUS Monitor.

In 2020, when COVID-19 was declared a pandemic and restrictions on free movement started to be implemented in many parts of the world, the CIVICUS Monitor found that the authorities detained activists for protest actions in at least 97 countries. Overwhelmingly, states pushed through emergency legislation to restrict civic freedoms and passed laws that were not in line with international standards of rights protections. In many cases this led to overcrowded prisons, due to high numbers of detentions of people found to have violated emergency laws. It became evident that what states characterised as a public health emergency response was being used by some to silence dissent and as a pretext to restrict freedom of peaceful assembly and other rights.

In 2022, with the pandemic under control, the arbitrary detention of protesters continued. Out of the 133 countries where protests were documented, protesters were detained for exercising their right to peaceful assembly in 90. Concerningly, 25 of these countries are rated as open or narrowed, which demonstrates that even countries with relatively enabling legislation and strong democratic institutions are not immune from politically motivated attacks on freedom of peaceful assembly.

As with harassment, arbitrary detention of protesters is used by most states, regardless of their civic space rating. It is used to prevent and disrupt protests, including protests that are political in nature, those that call for socioeconomic changes and demand improved service delivery, and those that express discontent with rising prices and the high cost of living.

In Iran, a wave of protests has been held since September 2022 following the death of Mahsa Amini, an Iranian Kurdish woman, while in police custody, after she was arrested by Iran’s morality police for allegedly breaching the country’s strict dress code. These large-scale protests have been met by a lethal and violent crackdown, with over 18,000 protesters detained by mid-December 2022.

In China, where large-scale protests are rare due to widespread repression and censorship, protests in several cities were documented, as people’s frustration with the state’s heavy pandemic restrictions made them take to the streets.

Undeterred by restrictions and determined to advocate for their rights, women in Afghanistan continue to protest, despite the risks. For example, around a dozen women protested in the Afghan capital on 10 May 2022 against the Taliban's new mandate that women must fully cover their faces and bodies in public. Some were detained for two hours, questioned, threatened and warned that if they continued they would be imprisoned. Similarly, anti-government protests have persisted across Myanmar, despite the risk of arrest, torture and violence against protesters. Protests began in opposition to the 1 February 2021 military coup.

Political protests often lead to increased repression, particularly in Africa. In multiple countries, the CIVICUS Monitor documented the detention of protesters for demanding democratic policies and political transitions. In Chad in October 2022, hundreds were detained for protesting against the decision of the military junta to extend the transitional period by another two years. Similarly, in Guinea around a hundred protesters were arrested when people took to the streets after the military unilaterally announced a three-year transition plan in July 2022.

With the impacts of the pandemic and Russia’s war on Ukraine causing economic crises and exacerbating global inequality, impacting on the most vulnerable people, many have taken to the streets around the world to protest against rising prices, the high cost of living, inflation and strict economic measures imposed by states. In Albania, several protests were held in March 2022 against rising oil and gas prices. According to reports, around 200 people were arrested in these protests on charges of ‘illegal gathering’ and ‘breaking up public order’.

High inflation in Uganda sparked protests in 2022. In one instance, police officers arrested six women protesters, charged them with inciting violence and unlawful assembly and remanded them in prison. In Panama, after weeks of protests demanding government action to address the rising cost of living and fuel and food price increases, the police responded by arresting at least 102 protesters.

Similar responses were documented in South Korea, where the authorities detained striking truck drivers who were demanding better wages. In Mongolia, protesters were detained and beaten by police after protesting against government inefficiency, debt burdens and inflation.

In many countries rated as open, the authorities are commonly responding to climate activism by detaining protesters. In Canada, four people were arrested at a protest against the construction of a housing project on a wetland that plays a vital role in absorbing greenhouse gases.

In the Netherlands in March 2022, around 18 Extinction Rebellion Netherlands activists were arrested in Amsterdam. They had gathered to raise awareness of the urgency of the climate crisis ahead of municipal elections. A few months later, in July 2022, around 40 climate activists from the Extinction Rebellion group were arrested as they demonstrated against government fossil fuel subsidies. Similarly, Extinction Rebellion activists were detained in Denmark in May 2022 for demanding climate action. Similar responses by the authorities towards Extinction Rebellion group actions were documented in Finland.

In Sweden, activists from the Fridays for Future global environmental movement were arrested in April 2022 while protesting to demand the restoration of Sweden’s wetlands and to raise awareness of the climate crisis.

In Germany, a 19-year-old woman was arrested for causing a disruption during a protest action in which she glued herself to the ground to block a road, in what she saw as a necessary act of civil disobedience to urge the government to take climate change seriously and reduce fossil fuel use.

Violations of the right to peaceful assembly have been among the most common restrictions documented by the CIVICUS Monitor over the past five years. Restrictions have not deterred activists from continuing to take to the streets to demand governments uphold their obligations to protect human rights. Rather, in many instances, protest actions have gone on to call for more systemic changes, with the understanding that violations will continue until governmental policies reflect international standards of human rights protection, not only in words but in practice, with constitutional guarantees realised for all people living within a country’s borders.

*For some countries in the Caribbean – Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Dominica and Suriname – the CIVICUS Monitor added more indicators this year compared to 2021. Therefore ratings changes were prompted by additional information rather than a change in the situation on the ground.