Asia Pacific

Rating Overview

The main civic space violations documented in Asia and the Pacific over the past year are the arbitrary detention of protesters and the use of excessive force by security forces against peaceful protests. Another widespread trend was the detention of HRDs and the use of an array of restrictive laws and trumped-up charges to prosecute them. Governments also used censorship in many countries in the region to silence expression, block criticism of those in power and deny people access to information.

In Asia, seven countries and territories are rated as closed: Afghanistan, China, Laos, Myanmar, Hong Kong, North Korea and Vietnam. Nine countries are rated as repressed: Brunei, Cambodia, India, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka and Thailand, along with Bangladesh, which has been upgraded from a closed civic space rating.

Six countries are now in the obstructed category: Bhutan, Indonesia, Malaysia, Maldives and Nepal, along with Mongolia, which has been downgraded to this category.

South Korea and Timor-Leste retain their narrowed civic space rating while Japan has now joined Taiwan as the only two countries rated open in the Asia.

The civic space situation is more positive among Pacific countries, with seven rated as open. Five are rated as narrowed: Australia, Solomon Islands, Tonga and Vanuatu, joined by Fiji, which has been upgraded to this category. Nauru and Papua New Guinea remain in the obstructed category

Bangladesh’s upgrade results from steps taken by the interim government to address civic space concerns following mass protests that led to the fall of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and her government in August 2024. This includes the release of protesters and HRDs. The government has signed the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances, formed a commission of inquiry on all cases of enforced disappearances and scrapped the jail terms resulting from the convictions of two HRDs from Odhikar, a leading human rights CSO. Despite this, more work is needed to protect journalists, repeal restrictive laws, ensure an enabling environment for civil society and pursue accountability for past crimes.

Japan’s upgrade to an open rating reflects the fact that over the year, civil society groups have been able to undertake their work without barriers and the right to peaceful assembly has generally been respected and protected. Further, media have been able to operate without major restrictions. However, concerns remain that business interests and pressure from politicians often prevent journalists completely fulfilling their role as watchdogs, while national security laws impose some restrictions on journalists.

In Fiji, upgraded from obstructed to narrowed, the government that came to power in December 2022 has taken steps to improve civic space, including by repealing a restrictive media law used to silence the press since 2010 and reversing politically motivated travel bans against government critics. It has also taken steps to strengthen the independence of the Fiji Human Rights and Anti-Discrimination Commission and is establishing a Truth and Reconciliation commission to address past abuses. However, the Public Order (Amendment) Act, which has been used to restrict peaceful assembly and expression, remains on the books and Palestinian solidarity protests have been blocked.

Mongolia has however been downgraded to an obstructed rating. This is because HRDs have faced reprisals, particularly those working to defend cultural, economic and social rights. Further, provisions of the Criminal Code related to ‘cooperation with foreign intelligence agencies’ have been used to criminalise HRDs for their legitimate activities. Journalists, including Bayarmaa Ayurzana and Naran Unurtsetseg, have been targeted on baseless charges for their work and peaceful protesters have been criminalised.

Protests repressed

Protesters were detained in at least 22 countries in the Asia Pacific region. In addition, in at least 10 countries, security forces used excessive force, leading to injuries and in some cases unlawful killings. Journalists and protest observers were targeted in some instances. Among the protesters targeted were those calling for democratic reforms, environmental rights, Indigenous rights, labour rights, accountability, equality, justice and end to the human rights violations in the OPT.

The crackdown on protests is particularly strong in South Asia as governments have sought to stifle the opposition, ethnic minorities and students, among others. In Pakistan, the government severely cracked down on the opposition around the February 2024 election, particularly protesters linked to Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party. Scores of protesters were attacked with batons and sticks and arbitrarily detained by the police across the country. In May 2024, police met protests against rising costs in Pakistan-administered Kashmir with arrests and teargas while in July 2024, hundreds were detained in response to a march seeking to raise awareness of human rights concerns in Balochistan, with excessive force used to prevent protesters reaching the port city of Gwadar.

In Bangladesh, hundreds were detained as part of a brutal crackdown on the mass student-led protests in July 2024 that ultimately brought down the Sheikh Hasina regime. At least 600 people were killed by security forces and by the Awami League’s student wing. Others suffered torture and ill-treatment in detention. Firearms, teargas, stun grenades, rubber bullets and shotgun pellets were used to disperse protesters, injuring many.

In Sri Lanka, police cracked down on opposition protests over rising costs and protests by students from the Inter-University Students’ Federation and teachers. In February 2024, security forces shot teargas and fired water cannon at Tamil students from Jaffna University who protested at the government’s failure to resolve issues faced by people in east and north Sri Lanka. Some were arrested and ill-treated. A crackdown on protests, particularly by pro-monarchy groups, was also documented in Nepal, with arbitrary arrests and excessive force.

In India, farmers from Haryana Punjab and Uttar Pradesh states who protested to demand support from the government in February 2024 were met with excessive police force to stop them entering Delhi. More than 100 protesters were injured. The government also blocked roads with heavy barricades, iron nails and barbed wire and deployed drones to drop teargas shells on protesters.

In Indonesia, security forces repressed multiple protests in the Papua region, home to an independence movement and consequently a region with a high level of violations. In April 2024, at least 27 protesters were detained and eight injured at a peaceful protest in Nabire in response to a video showing soldiers torturing an Indigenous Papuan person. In August 2024, over 200 protesters were arrested and 41 injured at gatherings led by the West Papua National Committee, a Papuan civil resistance movement demanding an independence referendum. There was also a brutal crackdown by police and the military on protests in August 2024 across cities in Indonesia over plans to pass an amendment to a regional election law. Over 200 protesters, including minors, young people and students, were arbitrarily arrested and some were denied access to legal aid.

Other countries in Southeast Asia where protesters were detained or excessive force was used include Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar and Thailand.

The space for protests remains extremely restrictive in China. Police arrested hundreds of Tibetans in Sichuan province in February 2024 after they protested against the construction of a dam expected to destroy six monasteries and force the relocation of two villages. In Hong Kong, several people involved in 2019 democracy protests were convicted and handed jail sentences, and authorities arrested others around the Tiananmen Square Massacre anniversary in June 2024.

In the Pacific, protesters across Australia mobilising on climate and environmental issues and in solidarity with Palestinians have faced detention. Arrests and excessive force were documented at a protest outside a weapons exhibition in Melbourne in September 2024. Protest observers reported the use of pepper spray, teargas, rubber bullets and flash-bangs against peaceful protesters, with some being punched and having their heads slammed against walls. Protest observers were themselves assaulted.

Human rights defenders detained and prosecuted

HRDs were detained and prosecuted over the past year in at least 15 countries in the region. Many were criminalised under anti-terrorism, criminal defamation, national security and public order laws. In addition, transnational repression, where countries collaborate to target HRDs beyond their borders, is on the rise.

The criminalisation of HRDs remains pervasive in China, where the authorities use broad and vague provisions of ‘subversion of state power’ and ‘picking quarrels and stirring up trouble’. Those convicted over the year include woman HRD Li Qiaochu, journalist Sophia Huang Xueqin and labour activist Wang Jianbing. Some activists are held incommunicado and tortured or ill-treated in detention. In Hong Kong, dozens of HRDs remain behind bars. In May 2024, 14 activists were convicted under the draconian National Security Law for organising, joining and supporting unofficial primary elections in 2020. In the same month, eight people were arrested on sedition charges under article 23 of the new Safeguarding National Security Ordinance, including

imprisoned HRD Chow Hang-tung. The UN has found both laws inconsistent with international law. The authorities have also offered bounties for activists in exile.

Scores of HRDs were detained on trumped-up charges in Vietnam over the year, including for ‘propaganda against the state’ and ‘deliberately disclosing state secrets’. They include blogger Nguyen Chi Tuyen, journalists Nguyen Vu Binh and Truong Huy San, labour rights activist Nguyen Van Binh, trade unionist Vu Minh Tien and lawyer Tran Dinh Trien. In addition, in March 2024 two ethnic Khmer Krom activists who distributed books about Indigenous rights were sentenced to prison for ‘abusing democratic freedoms’. There have been reports of activists facing torture and ill-treatment in detention. Activists in Vietnam also experience transnational repression, including Y Quynh Bdap, who faces extradition from Thailand on baseless charges.

HRDs detained across prisons in Myanmar by the junta continue to face fabricated charges for their activism. Protest leader Ko Wai Moe Naing was found guilty of high treason under Penal Code article 122 in May 2024 and sentenced to 20 years jail by a junta court, taking his total jail time to 54 years. There are continued reports of political prisoners held by the junta being tortured and killed in detention with no one held accountable for these crimes.

In Cambodia, ‘incitement’ laws have been used to target HRDs. In April 2024, Koet Saray, president of the Khmer Student Intelligent League Association, was detained after meeting villagers following an eviction. In July 2024, 10 activists associated with the Mother Nature environmental group were convicted and sentenced for ‘insulting the king’ and ‘plotting’.

Thailand’s lèse-majesté provisions (article 112), which criminalise criticism of the monarchy, have been used to detain and convict HRDs for speaking out, including human rights lawyer Arnon Nampa. Detained activist Netiporn ‘Bung’ Sanesangkhom died in May 2024 following a hunger strike against her arbitrary detention. No one has been held accountable for her death. HRDs in Malaysia, the Philippines and Singapore have also been prosecuted for their activism.

In India, HRDs have been detained under the restrictive draconian Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, an anti-terrorism law. At least eight HRDs are still detained under the Act on trumped-up charges after violence broke out in Bhima Koregaon village in Maharashtra state in 2018. Others detained include student activists Gulfisha Fatima and Umar Khalid, who participated in protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, which discriminates against Muslims. Kashmiri HRD Khurram Parvez, arrested in 2021, remains incarcerated in a maximum-security prison in Delhi in reprisal for his human rights work.

In Pakistan, authorities have targeted Baloch activists and those who have spoken up for them with arrests and detention. In July 2024, authorities brought sedition charges against woman HRD Mahrang Baloch. In Afghanistan, where UN experts have raised concerns about gender apartheid, the Taliban have sought to silence and create a climate of fear for HRDs, particularly women, who have been arbitrarily arrested, disappeared and tortured in detention. In February 2024, woman HRD Manizha Siddiqi was forcibly disappeared by the Taliban. She was sentenced to two years in prison in February 2024 for her involvement in protests. Critical academics have also been arrested and criminalised.

In Australia, former army lawyer David McBride was sentenced to five years and eight months in prison for revealing information about alleged Australian war crimes in Afghanistan. A climate activist was sentenced to three months in jail for a Newcastle coal terminal protest and union members have been convicted for their role in Palestinian solidarity protests.

Critical voices censored and journalists targeted

Censorship by governments was documented in at least 16 countries in the region. Over the year, the authorities used their powers to restrict access to information critical of the state by blocking television broadcasts and news portals, restricting access to social media apps, suspending mobile internet services and targeting journalists and news outlets. Censorship increased ahead of elections.

China employs one of the most sophisticated censorship regimes in the world, which it uses to block access to social media platforms, websites and blogs critical of the Chinese Communist Party. In March 2024, Weibo removed from its search results discussions about an unusual move by authorities to cancel an annual news conference by the premier. In June 2024, it censored any online discussions about the Tiananmen Square massacre. The authorities have also continued to subject foreign journalists to surveillance and threatened them with non-renewal of work permits if they report on topics the government deems sensitive. In Hong Kong, the government banned a protest song, jailed journalists and deported a Reporters Without Borders representative. The North Korea regime continues to block access to foreign media, particularly from South Korea. Punishments for accessing or distributing such media include jail, forced labour and the death penalty.

States in Southeast Asia are also using censorship to harass and silence critics and journalists. In Myanmar the junta has shut off access to virtual private networks, which people use to circumvent banned websites and services and blocked-off access to encrypted messaging services. Dozens of journalists are in jail and some have been killed. In Malaysia, police have hauled up journalists for questioning over their critical reporting. In Singapore, the Protection against Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act has been used against anti-death penalty activists, bloggers and online media outlets. It is a sweeping law that permits a single government minister to declare that information posted online is ‘false’ and order the content’s ‘correction’ or removal. In Cambodia, most independent outlets have been shut down and independent journalists continue to face reprisals, including those in exile.

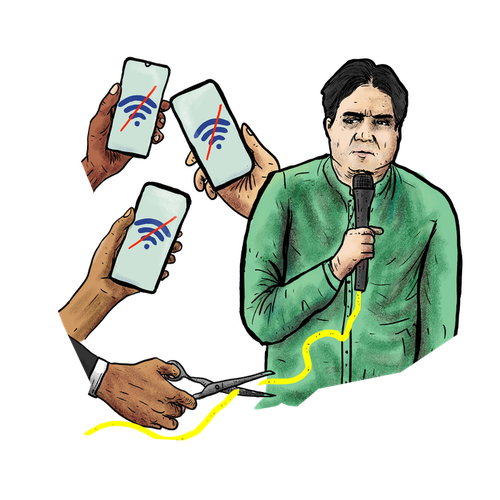

In South Asia, governments have taken steps to block the flow of information, particularly around elections. Pakistan suspended mobile internet services and X/Twitter across the country around the February 2024 election, citing national security concerns. It has also targeted journalists for their reporting, including Asad Ali Toor and Imran Riaz Khan for their criticism of the military. In Bangladesh, ahead of the January 2024 election, authorities refused to issue visas to foreign journalists and blocked the Daily Manab Zamin news portal. Journalists were assaulted and harassed while covering alleged election irregularities. As mass anti-government protests erupted in July 2024, authorities restricted access to mobile internet services across Bangladesh, and blocked access to social media platforms in some areas.

Ahead of the April-to-June election, in January 2024 the Indian government blocked two websites reporting on hate speech and related crimes. The following month it ordered The Caravan outlet to take down an article from its website about allegations of torture and killings in army custody in Jammu and Kashmir. In June 2024, cable operators in Andhra Pradesh state blocked access to four TV news broadcasters for their critical reporting during state-level elections. In Nepal, journalists have faced arrests, attacks, harassment and TikTok bans, while in Sri Lanka, journalists, particularly those reporting on the Tamil community, have been subjected to arrests, harassment and threats. In Afghanistan, the Taliban have shut down media outlets and arbitrarily arrested and detained journalists.

In the Pacific, there are censorship concerns in Nauru, with asylum seekers being held there on an Australian government programme denied smartphones and access to apps such as WhatsApp to communicate with families. Further, humanitarian websites are blocked on shared computers. In Solomon Islands in June 2024, Facebook temporarily blocked posts by independent online news outlet In-Depth Solomons, a member centre of the non-profit Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. In Papua New Guinea, journalists have faced restrictions and harassment for their reporting.

Countries of concern: Cambodia and Pakistan

There are serious concerns about the ongoing regression of civic space in Cambodia. Prime Minister Hun Manet, who took over from his father in August 2023, has continued an assault on fundamental freedoms by targeting HRDs, including environmental and land activists and trade unionists. Among those affected are Mother Nature activist Eang Vuthy and others from the group, Koet Saray and labour rights group the Center for Alliance of Labor and Human Rights. Reprisals against journalists continued to be reported while opposition members were arrested, harassed and attacked with impunity. The Law on Associations and Non-Governmental Organisations continues to be weaponised to silence civil society while the government has also been involved in transnational repression of Cambodia activists abroad.

Another country of concern is Pakistan. HRDs continue to be blocked from travelling, detained or prosecuted, including Mahrang Baloch and lawyer Zainab Mazari-Hazi, forcibly disappeared and killed with impunity. Prominent Sindhi activist Hidayatullah Lohar was shot dead in February 2024. HRD Idris Khattak is currently serving a 14-year jail sentence on trumped-up espionage charges. Over the year, Baloch activists in particular faced reprisals by state authorities for their activism. Members of the opposition Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party were also systematically targeted in what clearly seemed an attempt to crush the party. Protests by the opposition, ethnic minorities and women activists have faced restrictions, including arrests and the use of firearms and other forms of excessive force. Freedom of peaceful assembly is subject to significant restrictions and a new law to further regulate protests in the capital, Islamabad, was bulldozed through parliament in September. Journalists have been criminalised, threatened and killed and the authorities have blocked internet and social media platforms.

India and Cambodia

| COUNTRY | SCORES 2024 | 2024 | 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 |

| AFGHANISTAN | 13 | |||||||

| AUSTRALIA | 72 | |||||||

| BANGLADESH | 24 | |||||||

| BHUTAN | 59 | |||||||

| BRUNEI DARUSSALAM | 33 | |||||||

| CAMBODIA | 27 | |||||||

| CHINA | 12 | |||||||

| FIJI | 62 | |||||||

| HONG KONG | 15 | |||||||

| INDIA | 31 | |||||||

| INDONESIA | 46 | |||||||

| JAPAN | 84 | |||||||

| KIRIBATI | 83 | |||||||

| LAOS | 7 | |||||||

| MALAYSIA | 47 | |||||||

| MALDIVES | 46 | |||||||

| MARSHALL ISLANDS | 84 | |||||||

| MICRONESIA | 84 | |||||||

| MONGOLIA | 60 | |||||||

| MYANMAR | 12 | |||||||

| NAURU | 49 | |||||||

| NEPAL | 46 | |||||||

| NEW ZEALAND | 89 | |||||||

| NORTH KOREA | 2 | |||||||

| PAKISTAN | 30 | |||||||

| PALAU | 92 | |||||||

| PAPUA NEW GUINEA | 60 | |||||||

| PHILIPPINES | 34 | |||||||

| SAMOA | 81 | |||||||

| SINGAPORE | 31 | |||||||

| SOLOMON ISLANDS | 71 | |||||||

| SOUTH KOREA | 75 | |||||||

| SRI LANKA | 31 | |||||||

| TAIWAN | 81 | |||||||

| THAILAND | 28 | |||||||

| TIMOR-LESTE | 69 | |||||||

| TONGA | 76 | |||||||

| TUVALU | 88 | |||||||

| VANUATU | 79 | |||||||

| VIETNAM | 18 |