Asia Pacific

Rating Overview

In 2022, the CIVICUS Monitor continued to document restrictions and attacks on civic freedoms across the Asia Pacific region. As most governments lifted controls in relation to the pandemic, efforts to stifle dissent and crack down on civil society and social movements remained prevalent and escalated in some countries.

Among the most common violations were the passing and use of restrictive laws to criminalise activists and critics. In several countries these laws were used to prosecute HRDs and keep them behind bars for long periods. Another widespread trend across the region was the disruption of protests calling for political or economic reforms, with the authorities often detaining protesters and using excessive force. The authorities also harassed activists and protesters, including by hauling them in for questioning, detaining them, intimidating their families and imposing travel bans, in addition to digital attacks.

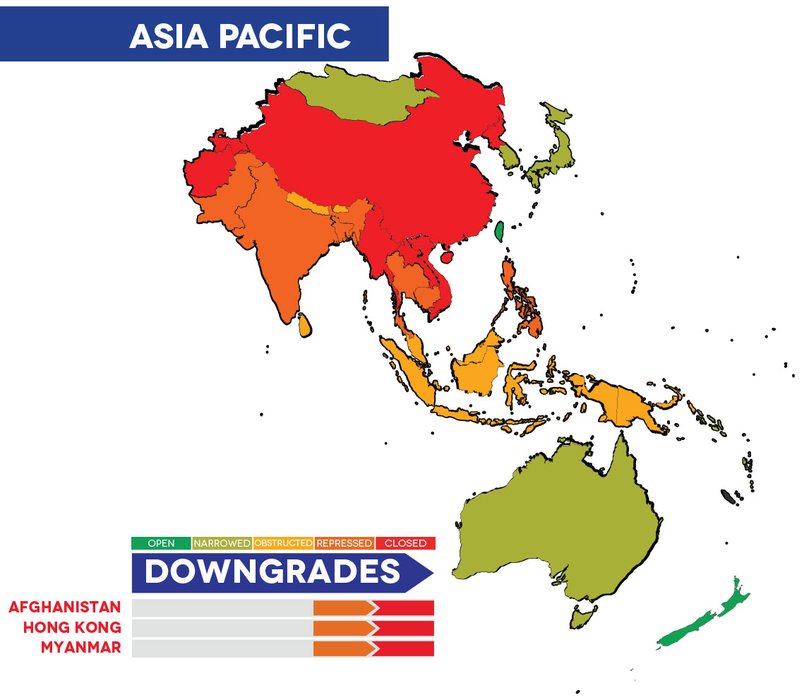

In the Asia region there is civic space regression with an increase in countries in the closed category from four to seven. China, Laos, North Korea and Vietnam, remaining in this category, are joined by Afghanistan, Hong Kong and Myanmar.

Eight countries are rated as repressed – Bangladesh, Brunei, Cambodia, India, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand – and seven are in the obstructed category: Bhutan, Indonesia, Malaysia, Maldives, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Timor-Leste. Civic space in Japan, Mongolia and South Korea is rated as narrowed, with Taiwan remaining the only country rated as open.

In the Pacific the civic space situation is better with seven countries rated as open and four as narrowed: Australia, Solomon Islands, Tonga and Vanuatu. Fiji, Papua New Guinea and Nauru remain in the obstructed category.

Graph: Change in Ratings for Region

All three countries downgraded to a closed rating have been on the CIVICUS Monitor Watchlist, alerting to a deterioration in civic space.

Afghanistan has been downgraded due to severe restrictions on civic space imposed by the Taliban following their takeover in 2021. Activists who have been critical of the Taliban have faced arrest, unlawful detention, abductions, torture and extrajudicial execution. Women rights activists protesting against discriminatory education and employment policies have been met by restrictions and violence. Journalists have been arrested, threatened and attacked while media outlets have been forced to shut down. The Taliban have also clamped down on CSOs, barred women from working in them and effectively banned political parties. They dissolved the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission.

In Myanmar, during two years of military rule following an illegal coup, thousands of activists, students, artists, lawyers, politicians and critics have been jailed by the junta in secret military tribunals on fabricated charges. The junta has continued to torture detainees with impunity and four activists were executed in July 2022. Scores of journalists have been detained and at least four were killed at the end of 2022, while media outlets have been banned. The arrest and jailing of anti-coup protesters has also persisted. Many civil society groups have shut down their offices. In October 2022, the junta enacted a new NGO law that will further shackle what is left of civil society.

Hong Kong has been downgraded due to the systematic crackdown on dissent following the passage of the draconian National Security Law in 2020. It punishes secession, subversion, terrorism and collusion with ‘foreign forces’, which all carry a maximum life jail sentence. The crimes are vaguely defined and have become catch-all offences to prosecute activists and critics with heavy penalties. More than 200 people have been arrested under the security law and dozens of civil society groups and trade unions have disbanded or relocated since the law came into place. Activists have also been criminalised for sedition, while around 3,000 protesters have been prosecuted for their participation in peaceful gatherings and protests, such as Tiananmen Square vigils which until recently were held annually. Independent and pro-democracy media outlets have been targeted with raids and forced to close and journalists have been criminalised.

Civic Space Restrictions

The top civic space violations in the Asia Pacific region in 2022 were the enactment and use of restrictive legislation, followed by protest disruption, harassment, the detention of protesters and prosecution of HRDs.

Criminalisation of human rights defenders and critics

The most widespread civic space violation in the Asia Pacific region in 2022 was the use of laws to restrict fundamental freedoms, documented in at least 27 countries. Among the legislation most often used to stifle dissent were laws related to national security and anti-terrorism, public order and criminal defamation. HRDs were prosecuted under restrictive laws in at least 17 countries in the region.

In China, rated as closed, the ongoing crackdown worsened as President Xi Jinping sought an unprecedented third term in office. The authorities detained and prosecuted scores of HRDs in 2022 for broadly defined and vaguely worded offences such as ‘subverting state power’, ‘picking quarrels and provoking trouble’ or ‘disturbing public order’. In Hong Kong, the National Security Law and colonial-era sedition law were deployed to arrest and imprison activists. Among those detained under the security law is human rights lawyer Chow Hang-Tung, from the now-defunct Hong Kong Alliance, the main organiser of Tiananmen Square vigils.

Restrictive laws that establish offences such as ‘abusing democratic freedoms’ or ‘spreading materials against the state’ are used in Vietnam to keep more than a hundred activists in jail. The one-party state also use tax evasion laws to criminalise activists such as environmentalist Nguy Thi Khanh.

Thailand continued to charge, detain and convict critics for royal defamation under its lèse-majesté law, which carries a punishment of up to 15 years’ imprisonment, and also prosecuted protesters under an emergency decree introduced in response to the pandemic, which was lifted in September 2022. In Myanmar, fabricated charges of terrorism, incitement and sedition were used by the junta to jail thousands of activists. In Cambodia, ‘incitement’ provisions were used to criminalise activists and union leaders such as Chhim Sithar and to hold them in pretrial detention without bail. These provisions were further used to prosecute the political opposition.

In the Philippines, the authorities used a terrorist financing law to persecute humanitarian workers and activists. In Indonesia, the Electronic Information and Transactions Law (ITE Law) has been weaponised to silence online dissent: two HRDs were charged with defamation under the ITE Law for speaking up online about human rights violations connected to corporate crime in the Papua region, allegedly linked to government officials. In Papua, people involved in peaceful activism for independence continue to be prosecuted and imprisoned by the Indonesian authorities for treason. A new Criminal Code passed in December 2022 could further restrict civic freedoms. Singapore continued to use criminal defamation laws as well as the 2009 Public Order Act against activists and journalists.

In India, anti-terror laws such as the repressive Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act have been systematically used by the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi to keep student activists and HRDs – such as people the state alleges to have instigated violence in the village of Bhima Koregaon in 2018 – in detention. Among those detained under the law is Kashmiri HRD Khurram Parvez. The government also used the restrictive Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act to raid and harass critical CSOs such as the Centre for Promotion of Social Concerns and Oxfam India and block CSOs’ access to foreign funding.

In Bangladesh, the draconian Digital Security Act continued to be used to target journalists and critics, including those in exile such as Tasneem Khalil, chief editor of Netra News, while journalist Rozina Islam is facing charges under the Official Secrets Act for exposing corruption. In Pakistan, the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act was used against journalists and critics to criminalise online defamation while HRDs including Muhammad Ismail and Idris Khattak have been prosecuted on trumped-up charges.

In the Pacific region, the passage of anti-protest laws in Australia puts climate protesters at risk. Other concerns include the use of the Public Order Act to restrict protests in Fiji and laws in Samoa and Vanuatu that criminalise online defamation.

Crackdown on protests and detention of protesters

Another key violation documented in the region was the disruption of protests, which occurred in at least 25 countries including five countries in the Pacific. The CIVICUS Monitor documented the detention of protesters in at least 20 countries.

Unprecedented protests that erupted across China in December 2022, due to widespread public frustration with the government’s strict pandemic regulations, were met with restrictions, arrests and excessive force. Police installed barricades and deployed sophisticated surveillance tools to track down and detain protesters. There was widespread censorship of online posts and videos related to the protests.

In Cambodia, striking unionists from the NagaWorld Casino, who held regular protests, were detained at quarantine centres for allegedly violating COVID-19 protocols. Some were forced onto buses and driven to the outskirts of the city where they had to pay for their own transport home. Strikers, mostly women union members, experienced sexual harassment.

Riot police also used violent tactics in Thailand to disperse peaceful protesters, including in the context of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in November 2022, when they beat protesters with batons and fired rubber bullets. They also attacked journalists at the scene. In Indonesia, mass protests by Papuans against the central government’s policies and in support of independence were forcibly dispersed with unnecessary use of force. Arrests were made and injuries reported.

Protests in Bangladesh by the political opposition, students and workers were met with restrictions and excessive police force. In some instances, supporters of the ruling Awami League party were involved in attacks against protesters with impunity. In August and September 2022, there was a brutal crackdown by the government on nationwide protests by the main opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party against a hike in fuel and commodity prices and mismanagement in the energy sector. In December 2022, the authorities again disrupted an opposition rally with live ammunition, rubber bullets and teargas. Mass arrests were reported.

Sri Lanka was included on the CIVICUS Monitor Watchlist in 2022 due to a crackdown on mass protests, as the country suffered its worst economic crisis in decades. The authorities used sweeping emergency powers to curtail protests, make arrests and shut down social media networks. Human rights groups documented the use of excessive force by the police against protesters, with the deployment of water cannon, teargas and rubber bullets. Hundreds were arbitrarily arrested and there were allegations of torture and ill-treatment in detention, including denial of access to medical care and lawyers. The draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act was used to detain three student activists. Journalists reporting on the protests were assaulted by security forces.

There were also restrictions on protests and arrests of protesters by the authorities in Maldives. In April 2022, President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih issued a decree restricting anti-India protests as a threat to national security. In Nepal, protests against a contentious aid grant and fuel price hikes were disrupted with excessive force. The Taliban repressed protests in Afghanistan, especially by women’s rights activists, disrupting their protests by firing shots into the air and detaining, interrogating and ill-treating them. In some cases, teargas and batons were used. They also assaulted journalists and confiscated their equipment to stop them covering the protests.

In the Pacific, the disruption of protests was documented in Australia, Fiji, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea and Vanuatu. Papua New Guinea security forces opened fire on protesters in Jiwaka Province around the general election in August 2022, killing four men and injuring 15 others. In Australia, the police undertook a pre-emptive raid ahead of protests by Blockade Australia climate protesters in June 2022, arresting at least 40 people.

Harassment of activists and journalists

In at least 23 countries in the region the harassment of activists, journalists and critics was reported.

In China, the harassment of activists escalated to silence dissent ahead of the country hosting the Winter Olympics in February 2022. HRDs and some academics had their WeChat messaging app accounts restricted, with some unable to use their accounts entirely and forced to re-register. Around the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre in June 2022, the authorities ramped up surveillance of dissidents and placed dozens of democracy activists under house arrest or forced them temporarily to leave Beijing. Human rights groups also exposed how authorities are sending activists to psychiatric wards for medically unnecessary compulsory treatment or using the ‘residential surveillance in a designated location’ procedure – a form of enforced disappearance – to detain activists.

In the Philippines, activists continue to be red-tagged – accused of being communists – and then arrested on fabricated charges. People who have been red-tagged include community doctor Maria Natividad Castro and environmental activist Vertudez ‘Daisy’ Macapanpan. The authorities also brought perjury charges against 10 HRDs from the human rights group Karapatan, women’s rights organisation Gabriela and the Rural Missionaries of the Philippines in retaliation for their human rights work.

In Malaysia, the police brought scores of protesters, including activists and opposition politicians, in for questioning for holding spontaneous demonstrations related to corruption and price hikes and in opposition to the death penalty. Journalists and whistleblowers also faced harassment for their reporting. Activists and lawyers in Singapore faced police harassment for their activism against the death penalty and the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act continued to be used to curtail freedom of expression. In Indonesia, activists were subjected to hacking and intimidation via WhatsApp in July 2022 after they held a Twitter Space discussion on the blocking of multiple websites.

In 2022, the Bangladesh authorities coerced and intimidated families of victims of enforced disappearances to silence them and targeted families of journalists and activists in exile. They also vilified leading human rights group Odhikar and arbitrarily revoked its registration. In India, the government sought to block activists and journalists from travelling abroad including the chair of Amnesty International India, Aakar Patel, journalist Rana Ayyub and Kashmiri photojournalist Sanna Irshad.

In the Pacific, the CIVICUS Monitor documented the harassment of the media in Solomon Islands and the suspension of judges in Kiribati.

Countries of concern: Bangladesh and Cambodia

There are serious concerns about the regression of civic space in Bangladesh in recent years, including judicial harassment of and threats and attacks on HRDs, journalists and the political opposition. The Digital Security Act has been used to silence online dissent and target critics and journalists, including those in exile. The police have also cracked down on protests and there have been allegations of torture, ill-treatment and enforced disappearances committed by the security forces, including the Rapid Action Battalion, an elite anti-terrorism unit.

CSOs have been targeted, with the government arbitrarily revoking the registration of leading human rights group Odhikar and intensified its smear campaign against them. There has also been a sustained attack on the opposition in the lead up to the 2024 elections.

Another country of concern is Cambodia where repressive laws are routinely used to restrict civic freedoms and criminalise HRDs, trade unionists, youth activists, journalists and other critical voices. Prime Minister Hun Sen continued to use a draconian state of emergency law to severely restrict fundamental freedoms. The 2015 Law on Associations and Non-Governmental Organizations continues to restrict the right to freedom of association due to its onerous registration requirements, reporting obligations and broad grounds for denial of registration and deregistration. Independent media outlets have been silenced and Hun Sen has intensified his crackdown on the political opposition ahead of elections in July 2023.

| COUNTRY | SCORES 2022 | RATING 2022 | RATING 2021 | RATING 2020 | RATING 2019 | RATING 2018 |

| AFGHANISTAN | 13 | |||||

| AUSTRALIA | 72 | |||||

| BANGLADESH | 27 | |||||

| BHUTAN | 59 | |||||

| BRUNEI DARUSSALAM | 33 | |||||

| CAMBODIA | 27 | |||||

| CHINA | 12 | |||||

| FIJI | 60 | |||||

| HONG KONG | 15 | |||||

| INDIA | 31 | |||||

| INDONESIA | 46 | |||||

| JAPAN | 75 | |||||

| KIRIBATI | 83 | |||||

| LAOS | 7 | |||||

| MALAYSIA | 47 | |||||

| MALDIVES | 46 | |||||

| MARSHALL ISLANDS | 84 | |||||

| MICRONESIA | 84 | |||||

| MONGOLIA | 61 | |||||

| MYANMAR | 12 | |||||

| NAURU | 49 | |||||

| NEPAL | 46 | |||||

| NEW ZEALAND | 89 | |||||

| NORTH KOREA | 2 | |||||

| PAKISTAN | 30 | |||||

| PALAU | 92 | |||||

| PAPUA NEW GUINEA | 60 | |||||

| PHILIPPINES | 34 | |||||

| SAMOA | 81 | |||||

| SINGAPORE | 31 | |||||

| SOLOMON ISLANDS | 71 | |||||

| SOUTH KOREA | 75 | |||||

| SRI LANKA | 41 | |||||

| TAIWAN | 81 | |||||

| THAILAND | 28 | |||||

| TIMOR-LESTE | 56 | |||||

| TONGA | 76 | |||||

| TUVALU | 88 | |||||

| VANUATU | 79 | |||||

| VIETNAM | 18 |