Rights Reversed Report

CIVICUS is a global alliance of civil society activists and organisations dedicated to citizen action and civil society throughout the world. Established in 1993, CIVICUS has been headquartered in Johannesburg, South Africa since 2002, with additional hubs to engage the United Nations in New York and Geneva. CIVICUS is a membership-based alliance with more than 15,000 members from civil society in more than 175 countries. In 2016, CIVICUS developed a participatory research platform, the CIVICUS Monitor, to assess the state of civic space worldwide and offer insights into related trends, setbacks and developments. CIVICUS defines civic space as the respect in law, policy and practice for freedoms of association, peaceful assembly and expression and the extent to which states protect these basic rights.

CIVICUS Monitor Methodology

To capture civic space dynamics and developments on a global scale, the CIVICUS Monitor collaborates with over 20 civil society research partners from around the world. These partners produce country updates on civic space, drawing on a set of guiding questions and an array of primary and secondary sources. These country updates can also contain inputs from national civil society organisations (CSOs) and local and international media sources. The CIVICUS Monitor consolidates these inputs to identify top civic space violations as well as positive developments where, for example, civil society has reversed restrictive measures. CIVICUS researchers evaluate each of the incidents to identify the type of civic space violations that occurred and identify the victims and the action that led to the violation. This brief by the CIVICUS Monitor provides an overview of the global and regional civic space landscape over the last five years from 2019 to 2023, including the key trends affecting civic space conditions as documented in over 2,250 country updates. It provides graphs and data on key restrictions on civic freedoms and inspiring examples from around the world where civil society has affected change to protect rights.

To draw comparisons at the global level and track trends over time, the CIVICUS Monitor produces civic space scores and ratings for 198 countries and territories. A country’s civic space is rated in one of five categories – open, narrowed, obstructed, repressed and closed – according to the level of respect for and protection of fundamental civic freedoms. The CIVICUS Monitor map of the world shows a landscape of shifting civic space across five regions: Africa, the Americas, Asia and the Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). While the civic space landscape varies across the five regions, the current global outlook is bleak.

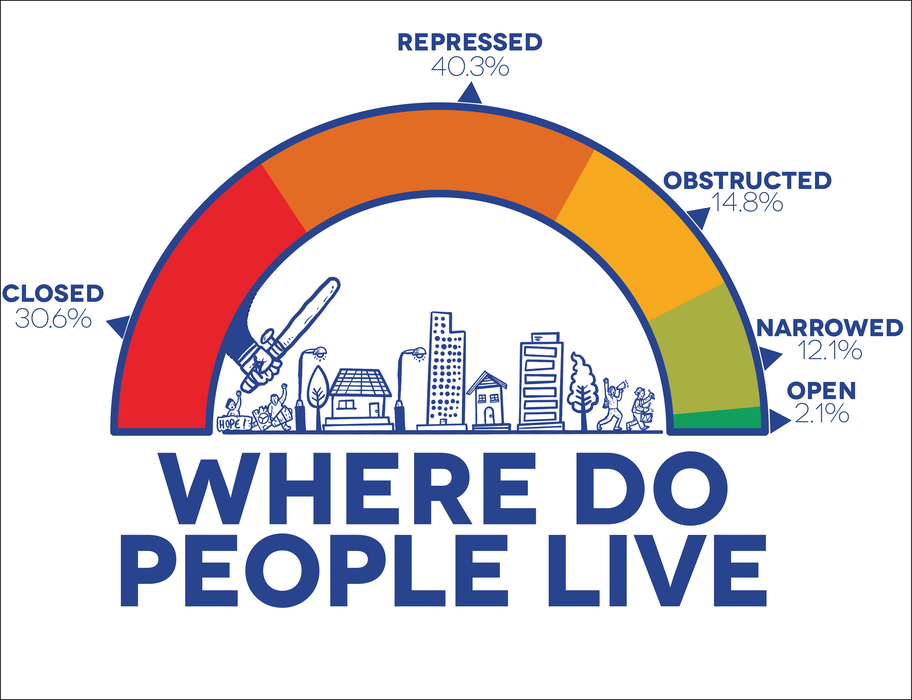

Since 2018, the CIVICUS Monitor has published its annual People Power Under Attack (PPUA) report, which analyses and details the civic space situation globally. According to the most recent report , published in December 2023, 40 countries are rated as obstructed and 50 as repressed, and there are 28 countries or territories with closed civic space, meaning that close to a third of the world’s population – 30.6 percent – lives in closed countries. Today, 118 of 198 countries and territories are in the obstructed to closed categories and thus experience severe restrictions on accessing and enjoying fundamental freedoms.

In comparison, 43 countries have narrowed civic space and 37 have an open rating. This means only two per cent of the world‘s population can freely access their rights to associate, protest and express dissent without significant constraints and limitations. This is down from the three per cent of the global population who lived in open countries in 2019, which means that 88 million people who used to live in open countries now experience some constraint on civic space.

As shown by the CIVICUS Monitor data above and the key trends outlined below, the rapid deterioration of civic space is a global crisis that requires a comprehensive and collective response. As open civic space is the foundation of a functioning democracy and civic freedoms are the bedrock on which other rights and freedoms are strengthened and protected, there is an urgent and immediate need for action to reverse the backsliding and safeguard civic space.

The main threats to fundamental freedoms globally, leading to a reversal in rights protection and a resulting decline in open civic space, include, but are not limited to, political movements and regimes restricting alternative voices and opposition, repressive legislation that curtails free speech and dialogue, obstacles to civil society activities and operations and crackdowns on civil disobedience and peaceful demonstrations, including with excessive force. Drawing on an analysis of developments from 2019 to 2023, the CIVICUS Monitor has identified the following seven key trends in civic space.

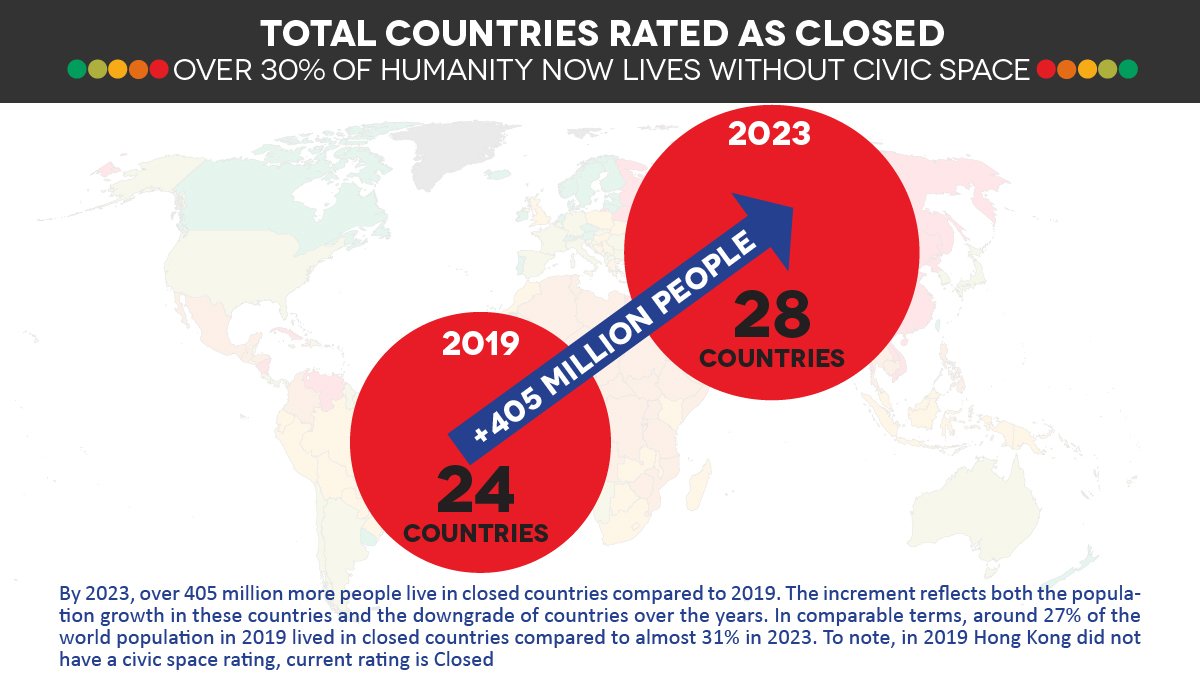

1. There is a discernible rise in the closure of civic space worldwide, with the highest number of people living in closed countries since 2019.

Over 2.4 billion people live in places where state and non-state forces routinely

imprison, harm or kill dissenters with impunity.

In 2019, 24 countries were rated as closed. Since then, six of these closed

countries

in Africa and MENA upgraded to the repressed rating due to some small

improvements in civic space conditions. However, conditions worsened for civil

society

in another 10 countries, bringing the current number of closed countries to 28,

meaning that 405 million more people live under severe repression. The

downgrades to the closed rating are primarily attributed to changes in the civic

space

situation of countries in the Americas, Asia and Europe and Central Asia.

In the Americas, Venezuela recently joined Cuba and Nicaragua on the list of countries rated as closed, where civil society faces severe consequences, including arbitrary detention, enforced disappearances, the closure of independent media and censorship, systematic attacks on activists and journalists and the enactment of repressive laws on dissent. The regimes of these three countries have intensified their control over civic space by taking punitive measures against civil society and independent media. Until 2021, only Cuba had been rated as closed in the Americas. In 2021, Nicaragua joined this category, following a crackdown on civil society that began in 2018, and Venezuela followed in 2023 as a result of the consolidation of its authoritarian policies.

The closed category in Asia – a region with some of the most populous countries in the world – grew from seven to eight countries and territories by 2023, with Bangladesh joining Afghanistan, China, Hong Kong, Laos, Myanmar, North Korea and Vietnam. Bangladesh was downgraded to closed due to an escalating crackdown on the opposition, activists, journalists and dissenting voices ahead of its general election in January 2024. The other seven countries have been in the closed category for between two and five years due to severe restrictions on the right to peaceful assembly and a high level of state control over freedom of expression, including surveillance and censorship. Additionally, in Myanmar, which is under military rule following a coup in 2021, thousands of activists, students, artists, lawyers, politicians and critics have been jailed by the junta in secret military tribunals on fabricated charges.

In the last two years, three countries in Europe and Central Asia – Belarus, Russia and Tajikistan – moved to the closed category, joining Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, which have been closed countries on the CIVICUS Monitor for the past five years. The closure of civic space in Belarus and Russia is a result of the shared tactics of repression between the regimes, with even minor opposition and anti-war protests being met with the use of excessive force and detentions. Simultaneously, authorities in the two countries have carried out a systematic campaign against civil society, with repressive legislation and criminalisation of activists leading to the liquidation of thousands of organisations. Moreover, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has led to a mass exodus of activists and journalists from the country as they would otherwise potentially face criminal charges for criticising or protesting against the war. In Tajikistan, the authorities have followed the example of neighbouring Central Asian countries as security forces responded to mass protests in 2021 and 2022 with excessive force, arbitrary detentions, torture and extrajudicial killings.

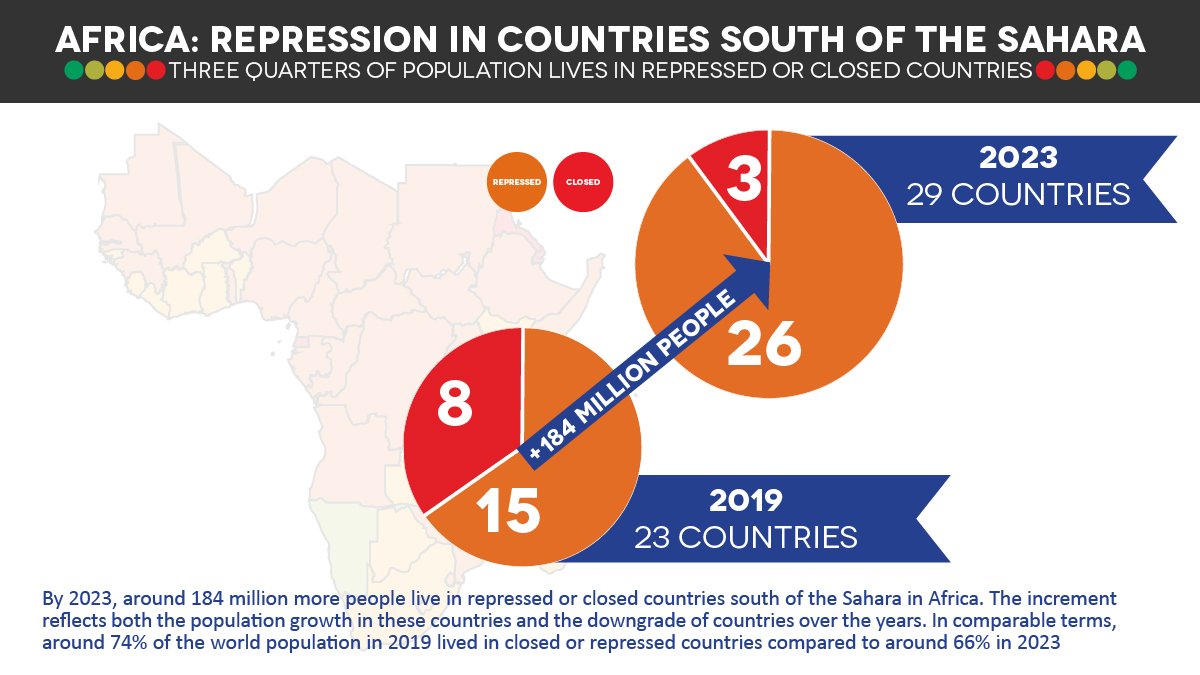

2. Repression remains the constant in Africa south of the Sahara and MENA

While the number of closed countries in Africa south of the Sahara has decreased over the past five years, from eight in 2019 to three in 2023, there has been a concerning increase in the number of repressed countries, six countries moved from the obstructed to the repressed category over the past five years. Now around three-quarters of the population of Africa south of the Sahara lives in the 29 countries where the civic space is significantly constrained or closed. This is a significant increase compared to the 23 repressed and closed countries five years ago. The countries of greatest concern in the region are those experiencing political instability, internal conflicts and military rule, among other challenges such as climate change, socioeconomic inequality and cross-border tensions. Authorities can take advantage of these challenges to consolidate and retain power and further limit civic freedoms.

To date, 90 per cent, 45 out of 50 countries and territories in the region, are rated as obstructed and repressed, with Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea and Eritrea closed. Civic space is open only in the island nations of Cabo Verde and São Tomé e Príncipe, while Mauritius, Namibia and Seychelles have narrowed civic space. The lack of movement in the direction of more open civic space over the last five years is a concerning trend, marked by increasing violations of freedom of expression and systematic suppression of dissent, indicating that a status quo of repression has been put in place across the region.

In this climate of repression, all three civic freedoms are under threat. In West Africa, press freedom violations have soared in the last year, including in countries ruled by military juntas. Following coups in Burkina Faso, Guinea and Mali, Niger experienced a military coup in July 2023, which was followed by repression of peaceful dissent, including the arrest of renowned activist and journalist Samira Sabou. Civic space in Central Africa remains severely affected by armed conflict, weak rule of law and impunity. Several journalists were killed in 2023 in Cameroon, while in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) the military shot and killed 50 people planning to protest. Countries in the East and Horn of Africa have reported high numbers of incidents involving the detention of journalists in the past five years along with rights violations against excluded groups. In Southern Africa, the situation for activists, journalists and whistleblowers remains a matter of grave concern as they frequently face threats, intimidation and restrictive laws that hinder their anti-corruption and human rights efforts.

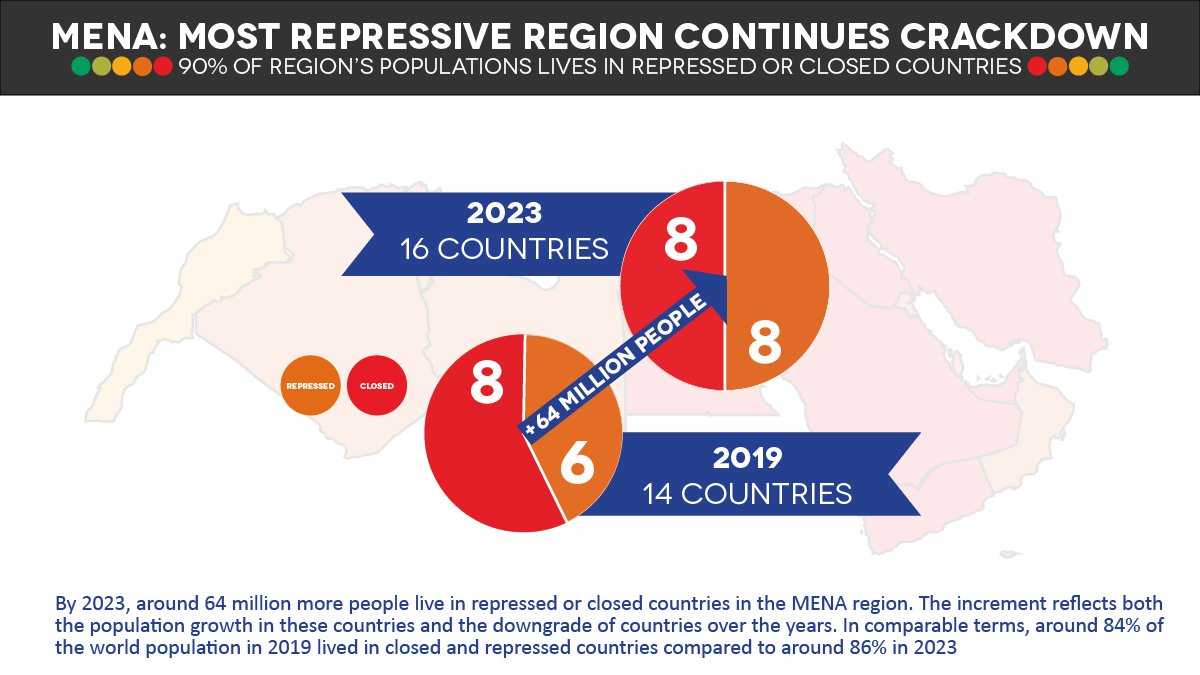

The MENA region continues to be home to some of the most repressive governments in the world. Sixteen out of the 19 countries are rated as repressed or closed. None of the countries in the MENA region has an enabling environment for the exercise and enjoyment of civic freedoms and around 90 per cent of the region’s population – at least 400 million people – lives in closed or repressed countries. The lack of open civic space is rooted in a number of issues. Among them are conflicts and wars – from the aftermath of the civil war in Libya to the ongoing bombardment in Syria and now Israel’s war on Palestine – have affected millions of people and their livelihoods and created the conditions for state and non-state sources to implement authoritarian policies.

Arbitrary and mass imprisonment of those perceived to be political opponents of governments continues unabated in the MENA region. In Tunisia, president Kaïs Saïed’s regime continues to crack down on critics and people with opposing views, including through detentions on security and graft charges. Censorship remains widespread, and governments in MENA routinely block access to independent information sources, as documented in Egypt, where in addition to mass imprisonment of those who oppose the military backed government, websites representing opposition voices and reporting on human rights-related issues have been made inaccessible . In addition, regimes in the region are notorious for causing internet and communications blackouts during critical times of mass protests and conflict, and around elections.

3. Civic space challenges come to the fore in Europe

Troublingly, rating changes over the past five years have shown that, in addition to the steady deterioration of civic space in countries experiencing political instability and a history of repression, previously stable and established democracies with strong institutions have also experienced a trend of declining civic space. Since the CIVICUS Monitor began tracking civic space conditions globally, Europe and Central Asia has been the region with the largest proportion of people living in places where they can enjoy freedoms of association, peaceful assembly and expression. In 2019, the region was the only one where the majority of people – 58.3 per cent – lived in countries with the two highest possible ratings of open and narrowed, with almost 20 per cent of people living in open countries. Five years on, however, this figure has almost halved to just over 10 per cent, and 54.3 per cent of people now face restrictions in either obstructed, repressed or closed countries.

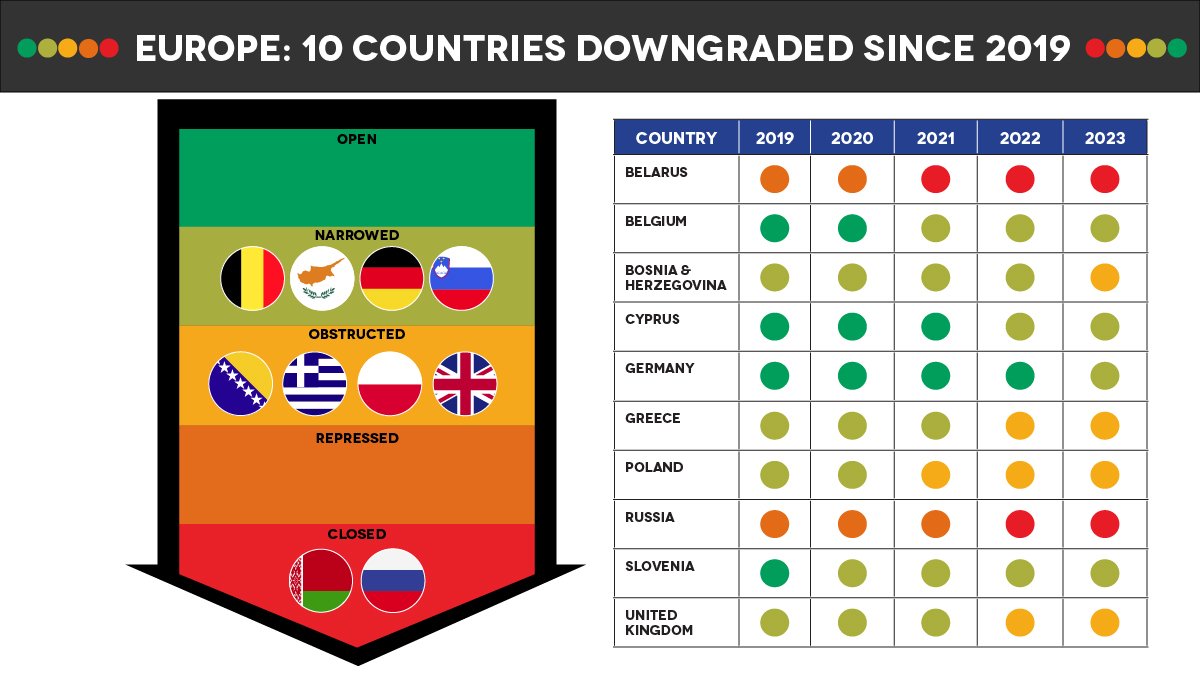

Out of the 13 downgrades in Europe and Central Asia over the past five years, 10 have been among European countries, with four countries in the European Union (EU) downgraded from open to narrowed as of 2023: Belgium, Cyprus, Germany and Slovenia. This narrowing of civic space has been linked to growing restrictions on protest rights and criminalisation of civil society activists. A particularly worrying trend in the EU in 2022 and 2023 has been the increasing government crackdown on the climate movement, with environmental activists arrested, prosecuted and intimidated in several countries for non-violent protest actions. In Germany, for example, activists belonging to the Letzte Generation (Last Generation) movement, which is known for its high-profile civil disobedience actions blocking traffic and targeting airports and museums, are under investigation for forming a criminal organisation, with authorities conducting house searches, seizing assets and blocking its online platform.

The criminalisation of solidarity actions among civil society is another point of concern. CSOs and activists providing aid to migrants and refugees, for example, have been targeted with criminal prosecution and investigation under anti-money-laundering and counter-terrorism provisions in Cyprus , Greece , Italy , Latvia , Lithuania and Poland .

Another concern is the sharper downgrades – from narrowed to obstructed – for Poland in 2021 due to attacks on women’s rights and LGBTQI+ people, and Greece in 2022 for the persecution of activists defending refugees and asylum seekers and for alleged state surveillance of journalists. The two countries joined Hungary was having obstructed civic space, showing that EU countries are not immune to attacks on civic freedoms. The UK, often referred to as one of the world’s oldest democracies, was also downgraded from narrowed to obstructed in 2022, due to the introduction of repressive laws that greatly expanded police powers and undermined the right to protest.

4. Detentions and arrests of protesters are used as a tactic to prevent and disperse protests and punish protesters.

Over the past five years, protests have sparked over dire

socioeconomic

situations, rising cost of living, shortages of essential goods and basic

services,

rising inequalities, climate change concerns, political power grabs

and alleged irregularities in the electoral process, with protests often being

the

only course of action people can take to address their grievances.

However, this right to seek change through peaceful protest is becoming

increasingly restricted

.

The detention of protesters consistently ranks as a top violation of civic space

documented over the past five years. Detentions took place in

countries ranked in all five civic space categories, from open to closed, with

at least 30 per cent of such incidents taking place in countries with open

to narrowed civic space, demonstrating that even countries with relatively

enabling legislation and strong democratic institutions can target protesters.

The detention of protesters is used to prevent and disrupt protests and punish

protesters for exercising their rights. Restrictions that precede protests

create a

chilling effect by generating an atmosphere of fear that discourages people from

exercising their right to peaceful assembly.

Examples include the arrest of opposition politicians in Sierra Leone ahead of anti-government protests, the detention of Extinction Rebellion climate activists in the Netherlands on charges of sedition for planning to block a highway, pre-emptive arrests of protesters in Jordan who planned to attend a march commemorating past anti-monarchy and pro-democracy protests, arbitrary arrests in Cuba targeting protest organisers and a pre-emptive raid leading to the arrest of Blockade Australia climate protesters in 2022.

Detention is not only used as a tactic to stop protests. It is also used to disrupt protests as people are gathering and during protests to break them up. The arbitrary arrest of protesters is a widespread tactic globally and has been seen in Europe as a response to climate protests. For example, in May 2022, over 100 protesters were arrested in Denmark for blocking bridges leading to central Copenhagen in order to demand fair and democratic action on the climate crisis. In 2023, climate activists were also detained in Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway and the UK for non-violent civil disobedience actions.

Together with detentions, excessive force is also frequently deployed to disperse protesters. In almost 40 per cent of disrupted protests documented in 2023, authorities used excessive force and arbitrarily detained protesters. In France, the police’s indiscriminate and excessive force during protests sparked by the killing of an unarmed teenager led to massive unrest, with over 3,000 detentions , including of children as young as 12. Bangladesh experienced mass arrests of opposition supporters, and police and ruling party supporters used live ammunition, teargas, rubber bullets and sticks against protesters. In Peru, protests erupted after President Pedro Castillo’s removal from office, prompting the deployment of armed forces. The excessive use of force resulted in unlawful killings, injuries and arbitrary detentions. In Guinea, the military was deployed to assist police in quelling protests calling for a return to civilian rule, leading to clashes, detentions and at least two reported deaths.

5. The COVID-19 pandemic was used as a pretext to limit civic space

During the COVID-19 pandemic, states around the world invoked legal and policy measures to curb the spread of the virus. However, in some countries with already constrained civic space, authorities used the pandemic as a pretext to crack down on dissent and consolidate power, employing sweeping emergency measures and fast-tracking restrictive legislation that threatened civic freedoms. Freedom of peaceful assembly was particularly affected, with measures such as overly broad bans, mass arrests and the use of excessive and lethal force documented globally.

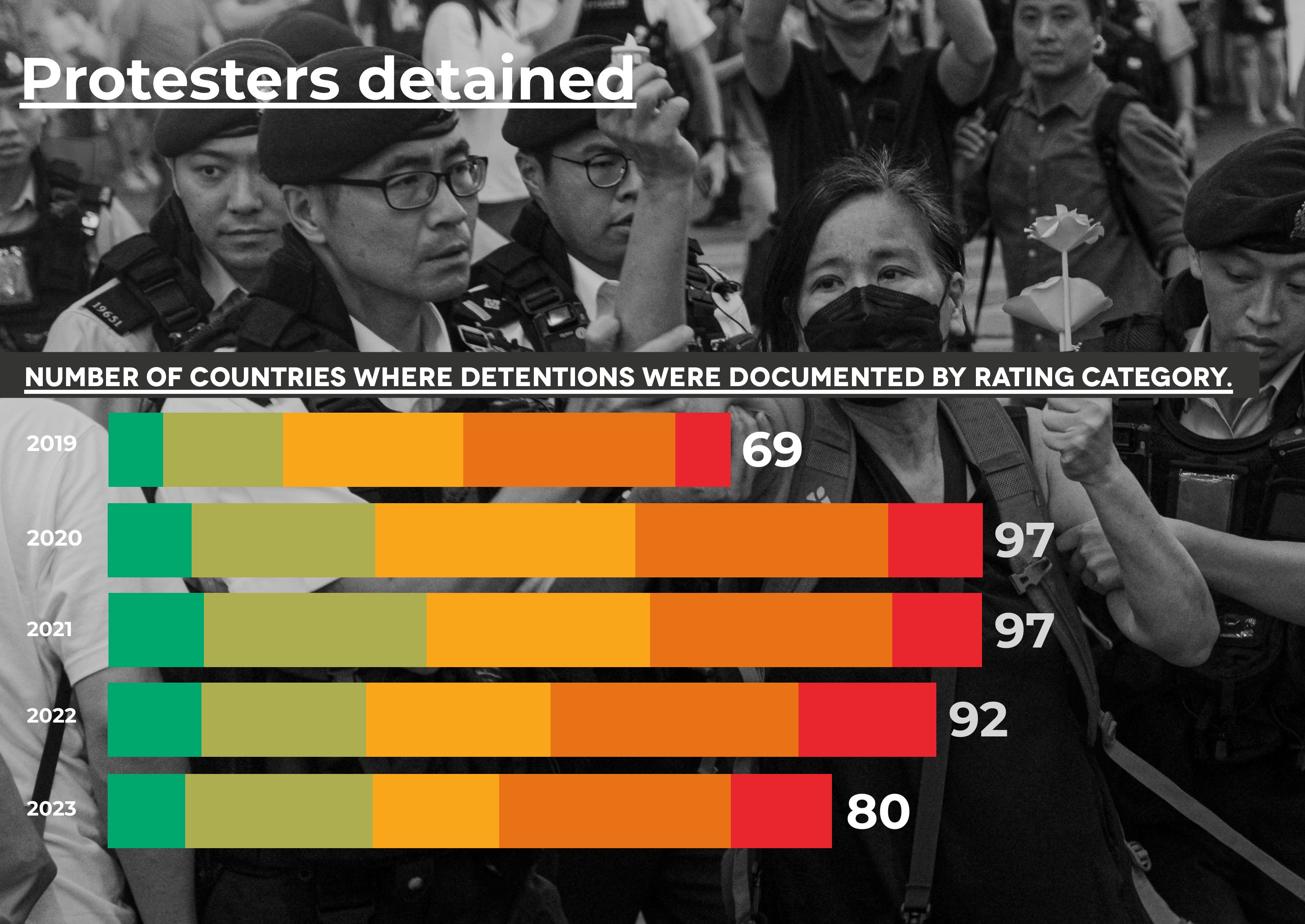

The CIVICUS Monitor found that

restrictions on protests, including the banning

and prevention of protests, peaked during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020 and

2021, detention of protesters was the top civic space violation documented in at

least 97 countries. The use of excessive force by security forces during

protests occurred in at least 79 countries during the pandemic period, including

Bangladesh,

Brazil, Ecuador, France, Indonesia, Kenya, Montenegro and Tunisia. Lethal force

was used against protesters across the world, including in Afghanistan, Belarus,

Guinea, Iraq, Nigeria, Uganda, the USA and Venezuela, and the killing of

protesters

was documented in at least 28 countries.

Emergency health measures continued to be used to restrict the right to

protest

even after the peak of the pandemic, particularly in Asia. For example, an

emergency decree on the COVID-19 pandemic continued to be used to ban protests

in

Thailand until the end of September 2022. In Hong Kong, the government blocked

all forms of protest as part of its crackdown on dissent and in June 2022, it

banned

public commemoration of the anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre

for a third consecutive year, citing risks from COVID-19.

In addition, people’s right to freely receive and impart information, indispensable during a global crisis, was severely restricted. According to a CIVICUS Monitor analysis of freedom of expression during the pandemic, at least 37 countries enacted or amended laws to curb the spread of disinformation, or otherwise detained or charged individuals for allegedly spreading disinformation about the pandemic. These restrictions further limited the space for free speech in already repressive environments, with countries where civic space is obstructed or repressed accounting for over half of the cases where restrictive legislation was passed.

Further, censorship related to the COVID-19 pandemic occurred in at least 28 countries globally between January 2020 and February 2021, with authorities seeking to suppress academic and media reports on the extent of the crisis and its handling, often through arrests and intimidation, and engaging in the widespread blocking of social media and online content. The CIVICUS Monitor recorded cases of journalists being physically attacked over their reporting of the pandemic in at least 24 countries and of detentions of journalists and media workers in at least 34 countries, in incidents related to their coverage of the pandemic or where pandemic-related restrictions were used to justify arrests.

6. prosecution of human rights defenders is a growing concern

The prosecution of human rights defenders (HRDs) is a growing concern, ranking among the top 10 violations documented by the CIVICUS Monitor in the last two years. Over the past five years, this troubling trend has escalated significantly. In 2019, the CIVICUS Monitor recorded prosecutions in at least 36 countries, a number that climbed to 66 in 2023.

This trend is particularly concerning in the Asia-Pacific region, where it is the fourth most frequently documented civic space violation. In Vietnam, more than 100 activists are in prison, jailed on trumped-up charges of ‘conducting propaganda against the state’ and ‘abusing democratic freedoms’. Indonesian authorities have used the Law on Electronic Information and Transactions to criminalise activists. In India, there is an increasing use of the draconian Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, an anti-terror law, against HRDs. In China, activists have been prosecuted under vague and broad provisions of ‘subversion of state power’ and ‘picking quarrels and stirring up trouble’. The Thailand government – a coalition that includes military-backed parties – has continued to charge, detain and convict critics for royal defamation under its oppressive lèse-majesté law, which can lead to a sentence of up to 15 years in prison. In the MENA region, HRDs face widespread prosecution. In 2023, the CIVICUS Monitor documented at least one prosecution of an HRD in 11 of the 19 countries of the region.

In Qatar, life sentences were upheld for lawyers arrested and charged

solely for supporting protests on social media.

In Iran, five HRDs received prison sentences

of between three months and

four years for attempting to file a complaint over mismanagement of the

pandemic. In Morocco, a blogger faced prosecution for criticising the

government. In Kuwait, another blogger was prosecuted

in connection with his

peaceful human rights work.

In Central Asia, criminal prosecution is frequently used as a means of

intimidation and suppression of dissent. Prosecutions of journalists and HRDs

are some of the region’s most common violations, with authorities targeting

dissenters with criminal charges such as slander, extortion, fraud, rioting

and extremism. Some particularly concerning trends are the use of extremism

charges

against government critics in Kazakhstan and Tajikistan and the

forced repatriation of outspoken activists abroad to Turkmenistan, accompanied

by pressure on their relatives in the country. In Tajikistan, as part

of the crackdown, human rights activists and journalists critical of the

government’s policies have been detained and prosecuted

, with others facing

intimidation and harassment.

Examples can also be found in Africa, the Americas and Europe. In The Gambia, a pro-democracy activist advocating for accountability and democratic principles, who has been repeatedly targeted, was arrested and charged with ‘seditious intention, incitement to violence, and false publication and broadcasting’ under The Gambia’s Criminal Code. In Honduras, members of the Garifuna community defending their territory have faced detention and criminal proceedings by the Public Prosecutor’s Office for alleged crimes such as damage, threats, theft and usurpation of lands. In Greece, 24 refugee aid workers have been subjected to criminal charges of espionage and forgery due to their involvement in migrant rescue operations in the Aegean Sea.

7. Restrictive laws are being used as tools to limit civil society activities

The CIVICUS Monitor has tracked how legislation is often used to censor opposition and silence critics, and to limit or shut down CSOs and civil society initiatives. In the United Arab Emirates, the increasingly retaliatory and punitive context forbids criticism of ‘the state or the rulers’ and imposes punishments, including life imprisonment and the death penalty, for association with any group opposing ‘the system of government’ under the Cybercrime Law.

The government in Bangladesh continues to use the Foreign Donations (Voluntary Activities) Regulation Act and the NGO Affairs Bureau, which sits under the prime minister’s office, to restrict and harass CSOs. In Hong Kong, the draconian National Security Law has been used to detain and prosecute democracy activists. Throughout 2021, the Vietnamese government used an array of vaguely defined laws such as ‘anti-state propaganda’ and ‘abusing democratic freedoms’ to charge and jail activists and bloggers, some with long prison sentences.

The legal situation for civil society in Venezuela is precarious. Under the current legal framework, including the 2010 Law for the Defence of Political, Sovereignty and National Self-Determination and the 2012 Organic Law on Organised Crime and Financing of Terrorism, the state undermines the ability of civil society, labour unions and political parties to organise and operate. Civil society groups estimate that over a quarter of CSOs operating in Venezuela have been unable to obtain legal status.

In Zimbabwe in 2023, President Emerson Mnangagwa signed the Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Amendment Bill (Patriotic Bill), which criminalises the lobbying of foreign governments to extend or implement sanctions against Zimbabwe or its officials. The law brings dire consequences for those found guilty, including a punishment of revocation of citizenship, and has been interpreted as a malicious attempt to muzzle the work of civil society and watchdog groups.

Civil society in Belarus faces multiple hurdles and a raft of laws that are used to systematically wipe out opposition movements, civic initiatives, human rights groups, independent media, labour unions and any other civic-led formation that the regime views as a potential threat. By the end of 2023, 940 organisations had been liquidated by court order and 550 had chosen to liquidate due to the threat of possible criminal prosecution under several laws, including anti-extremism and anti-terrorism laws that have been used by the state to target and discredit organisations and imprison people.

In Kyrgyzstan, two restrictive laws were fast-tracked through parliament in 2021: a law against ‘false information’, which critics describe as a censorship tool to protect government officials from criticism, and a law introducing a new financial reporting scheme for CSOs, which threatens to tighten state control. A draft ‘foreign agent’-style NGO law was resubmitted to the Kyrgyz parliament in May 2023 with broad support from politicians. If adopted, this law would require foreign-funded CSOs that carry out what are defined as ‘political activities’ to register as ‘foreign agents’ and subject them to excessive and discriminatory state oversight. The draft law has been heavily criticised by civil society, international experts and national government agencies.

Not all people are involved in or equally impacted on by civic space restrictions and limitations. The CIVICUS Monitor documents the groups involved in or affected by civic space incidents. From 2019 to 2023, LGBTQI+ people, environmental rights defenders and women’s rights defenders were consistently among those most involved in and affected by civic space incidents.

LGBTQI+ people:

The repression of civic freedoms have been particularly acute for LGBTQI+ people, organisations and initiatives for LGBTQI+ rights. This is a global phenomenon but particularly an issue in Africa, as documented in the CIVICUS report ‘Challenging Barriers: Investigating Civic Space Limitations on LGBTQI+ rights in Africa’, published in July 2023. LGBTQI+ people were the group most affected by civic space violations, including repressive laws and discrimination, both in law and in practice, throughout Africa south of the Sahara in 2022 and 2023.

In Uganda, for example, the CSO Sexual Minorities Uganda was suspended in 2022 for its failure to register, even though the organisation had attempted to register and its application had been denied. In Malawi, the Nyasa Rainbow Alliance’s request to be registered as a trust, made in 2016, has been repeatedly denied over the last six years. The first LGBTQI+ community centre in Accra, Ghana was forced to close after security forces raided it. Same-sex relations remain criminalised in at least 27 African countries and there are widespread bans on the publication of information on LGBTQI+ rights across the continent.

Environmental rights defenders:

Among the most at-risk activists to be targeted by state and non-state sources

are environmental

and land rights defenders, including Indigenous rights defenders and climate

justice activists. Protests by these groups are frequently criminalised. State

authorities and private companies systematically crack down on the rights to

peaceful assembly and dissent of these civil society activists,

groups and grassroots movements.

In a 2021 analysis of case studies on risks environmental rights defenders face,

the CIVICUS Monitor

found that such rights defenders and groups encounter repression on all

continents. In Cambodia,

for example, three environmental defenders were sentenced to 18 to 20 months in

prison for planning a protest against the filling in of a lake. In Finland, over

100 activists were arrested for participating in a protest calling for the

government to take urgent action on climate change.

The Americas continue to be the most dangerous region for environmental, land

and Indigenous

rights defenders. This is the only region where the killing of defenders is

consistently listed in the

top five civic space violations on the CIVICUS Monitor, with killings documented

in Colombia, Honduras and Mexico, among other countries.

Women and women human rights defenders:

The CIVICUS Monitor has documented the strength, resilience and fortitude of women and women human rights defenders (WHRDs) around the world, and particularly in the MENA region, where there is an ongoing struggle to advance gender equality. From taking a leading role in organising and mobilising protests in Lebanon’s 2019 popular uprising and participating in Iraq’s 2019 popular protests to taking to the streets in Iran in 2022 to 2023 to protest against femicide and police abuse of power, women are at the forefront of change and make significant sacrifices, sometimes putting themselves in danger, to stand for human rights. In Syria, for example, WHRD Hiba Ezzideen Al-Hajji and the Equity & Empowerment Organisation faced threats and defamation for defending women’s rights. In Saudi Arabia, WHRD Manahel Al-Otaibi was arrested for her work defending women, and her sisters faced intimidation, while WHRD Salma Al-Shehab received a 27-year prison sentence for her online advocacy.

CIVICUS Monitor country updates indicate when research partners have determined a positive civic space development, such as changes in laws and the release of jailed activists or journalists. These civil society victories are not confined to countries with open civic space or those experiencing ratings upgrades. Positive developments have been noted even in repressed and closed countries. This speaks to the resilience and endurance of activists, movements, independent media, journalists and citizens to defend and protect fundamental freedoms.

Civil society successes - from advocacy to campaigning

In every region, civil society uses advocacy mechanisms – both domestic and international and to whatever extent possible – and public campaigns to raise awareness of rights violations, call for accountability and demand respect for the rule of law.

In 2021, The Gambia’s National Assembly adopted an Access to Information Bill, a result of close collaboration between civil society and government departments. Several positive legislative developments were also documented in Romania following successful civil society advocacy. For example, the government adopted legal provisions that simplify the bureaucratic procedures for CSOs. In Bahrain, well-known activist Nabeel Rajab’s conditional release from prison came in 2020 after several years of civil society advocacy among diplomats and through raising awareness in the media.

Civil society in Denmark raised concerns over the ‘Security for all Danes’ bill, which would have allowed for police to issue a general ban on staying in a geographically defined area for 30 days if a group of people exhibited ‘insecurity-creating behaviour’ in the area. However, after civil society advocated directly with members of parliament, the government rejected this specific clause when adopting the law. In India, in response to cases lodged by several journalists and activists, the supreme court ordered an independent inquiry into whether the government used Pegasus surveillance software to spy illegally on activists, journalists and political opponents. In the USA, Florida’s abusive anti-protest law was blocked following a lawsuit filed by CSOs in a federal court, an important ruling to address efforts to criminalise protests.

Civic space improvements in law and practice

The CIVICUS Monitor documents instances of improvements in law and practice that have defended or expanded civic space. Tajikistan adopted a National Human Rights Strategy and its first action plan in August 2023. The groundwork for this strategy was laid in 2017, and the process involved close collaboration between the governmental working group and CSOs. Several of the recommendations put forward by civil society during the dialogue and development process were incorporated into the final version of the strategy

In 2021, the passage of a protection law for HRDs in Mongolia brought a major victory for the county’s civil society, ensuring that the right to association would be protected. More recently in the DRC, the passing of a Law on the Protection and Responsibility of Human Rights Defenders in 2023 marked a historic step in safeguarding those at the forefront of human rights advocacy. This victory, a culmination of efforts dating back to 2010, showed the resilience of civil society in the face of formidable challenges. In 2020, Bhutan’s parliament approved a bill to decriminalise same-sex relations, a major win for LGBTQI+ rights groups and campaigners.

Human rights groups have played a key role in accountability measures by helping to bring the authorities in Myanmar before the International Court of Justice for violations of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

People as powerful agents of change

People power can never be underestimated and even citizens who are not active rights defenders can mobilise as effective agents of change when civic freedoms are under threat. Grassroots organising, campaigning and protests enable people to gather and voice their opinions. In Sri Lanka, mass protests in 2022 led to the resignation of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who had presided over a climate of repression against activists, journalists and critics. In Hungary, a significant act of public protest, along with a campaign by human rights groups, led to a boycott of a referendum seeking endorsement of the government’s persistent anti-LGBTQI+ agenda.

Hundreds gathered on the streets in Lebanon over a proposed tax on WhatsApp calls and other messaging services. Although the tax was scrapped, the protests continued, as people mobilised over broader societal issues, such as corruption and ineffective public services. In Malawi, months of sustained public protests led to a historic rerun of presidential elections and a transition of power in 2020.

In Argentina, mass protests organised by the Marea Verde (Green Wave) led to the legalisation of abortion in December 2020. Argentina’s feminist movements achieved a landmark victory with the approval of a legal abortion law that they had campaigned for over decades. The effects of this achievement reverberated throughout Latin America and the Caribbean, where most countries criminalise abortion and some have outright bans.

The examples of reversing repression in section V are only a selection of the dozens of positive developments tracked by the CIVICUS Monitor from 2019 to 2023. Despite the adverse conditions and concerning trends described in section III, civil society has mobilised to enact positive change and bring about openings in civic space. Courageous acts of resistance give hope that the downward shift in respect for civic freedoms, detailed in section II, can be reversed.

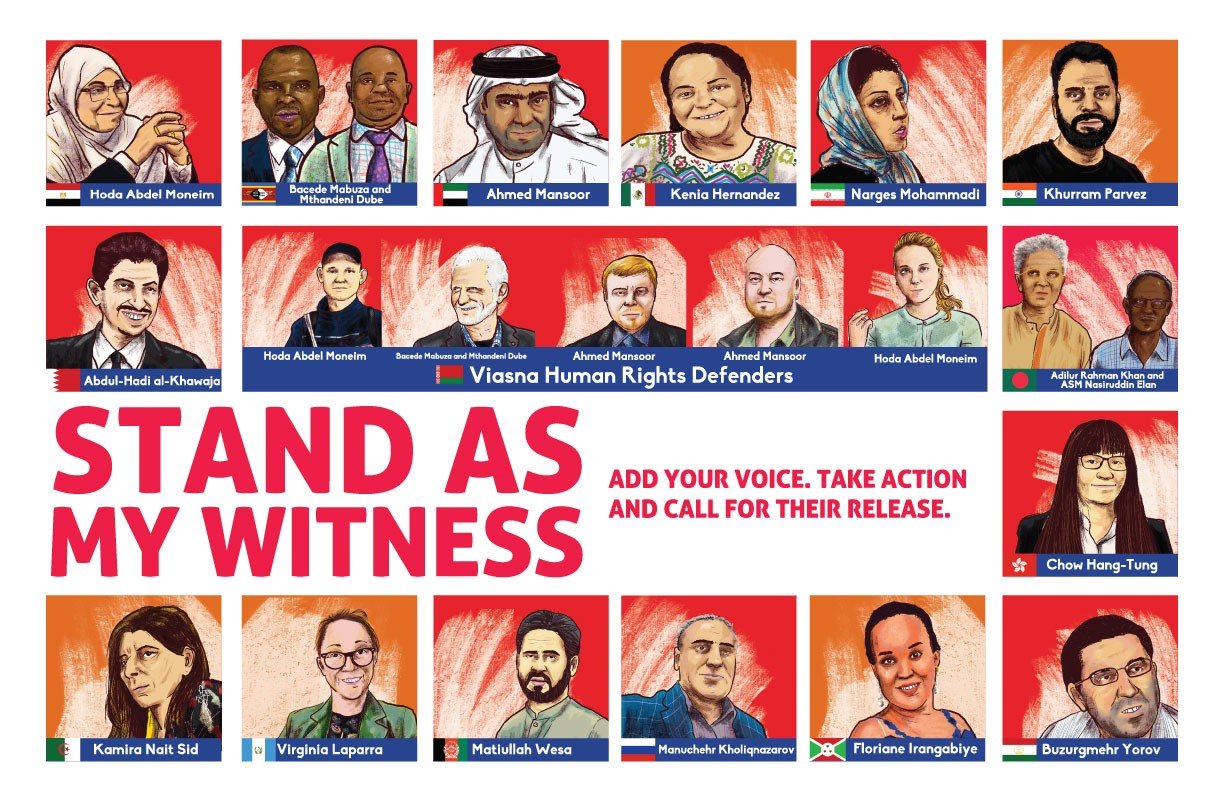

For civic space to flourish in the next five years, urgent action is needed now to support civil society and HRDs, in every country and context, from open to closed, with an emphasis on safeguarding the most vulnerable among civil society, including defenders of environmental, LGBTQI+ people’s and women’s rights. It is crucial to promote international acts of solidarity and campaigns on behalf of activists imprisoned or under pressure and to raise opposition – online and on the streets – when civic space is threatened.

VII. Recommendations to Safeguard Global Civic Space

- Take measures to foster a safe, respectful and enabling environment in which civil society activists and journalists can operate freely without fear of harassment, intimidation, attacks, or reprisals, in line with international human rights commitments.

- Work with civil society to establish effective national protection mechanisms that respond to the needs of those at risk.

- Repeal any legislation that criminalises HRDs, protesters, journalists and members of excluded groups. Ensure that adequate consultations are carried out with the public and civil society and that their input is taken into account before drafting laws that impact on freedoms of association, peaceful assembly and expression.

- Carry out independent, prompt and impartial investigations into all cases of attacks on and killings of HRDs and journalists and ensure those responsible are brought to justice to deter others from doing the same.

- Desist from using excessive force against peaceful protesters, stop pre-empting and preventing protests and adopt best practices on freedom of peaceful assembly, ensuring that any restrictions on assemblies comply with international human rights standards.

- Review and, if necessary, update existing human rights training for police and security forces, with the assistance of independent CSOs, to foster the consistent application of international human rights law and standards during protests, including the United Nations (UN) Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms.

- Establish fully independent and effective investigations into the use of excessive force by law enforcement officers and agencies during protests and bring to justice those suspected of criminal responsibility.

- Ensure that freedom of expression is safeguarded in all forms by bringing all national legislation into line with international law and standards and refrain from censoring social and conventional media. Any restrictions should be subject to oversight by an independent and impartial judicial authority and be in accordance with due process and standards of legality, necessity and legitimacy

- Maintain reliable and unfettered internet access and cease internet shutdowns that prevent people obtaining essential information.

- Repeal any legislation that criminalises expressions based on vague concepts such as ‘fake news’ or disinformation, as such laws are not compatible with the requirements of proportionality.

- Publicly condemn defamatory remarks, threats, acts of intimidation and attacks on HRDs and excluded communities.

- Take appropriate measures to fully implement all recommendations accepted by states made by UN Special Rapporteurs and Working Groups, including those from the Universal Periodic Review process of the UN Human Rights Council.

- Provide access for communities and civil society to engage in decision-making processes at the UN and work closely with states to ensure that laws, travel restrictions and technologies do not limit access to the UN.

- Pressure states to repeal or substantially amend restrictive legislation not in accordance with international law and standards in protecting freedoms of association, peaceful assembly and expression.

- Strengthen existing mechanisms and implement new ones to address reprisals against HRDs who cooperate with international and regional mechanisms.

- Take the necessary measures to ensure that activists and others in civil society are not put at risk because of the information they provide and publicly call out states that impose restrictions on civil society participation.

- Align policies with international human rights standards, including the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights..

- Provide long-term, unrestricted and core support for civil society in countries where civil society is facing increasing restrictions from states.

- Provide specific support to groups conducting advocacy in countries with rapidly closing civic space.

- Adopt participatory approaches to grant-making. Include human rights organisations in designing schemes and conduct situation assessments with CSOs. Maintain engagement at every stage, including when funding has been granted, to create adaptation and reallocation strategies with grantees in response to difficult working environments.

- Prioritise security. In sensitive cases, donors need to balance transparency and security needs. Where civil society and human rights work is criminalised or HRDs are under surveillance or facing harassment, key information such as the identity, operations, activities and location of those receiving funds might need to remain undisclosed. Donors should support programmes to ensure that HRDs have appropriate training, skills and equipment to conduct their work safely

- Adapt grant-making modalities to the emergence of social movements and youth activists, among other key elements of civil society.