Asia Pacific

Rating Overview

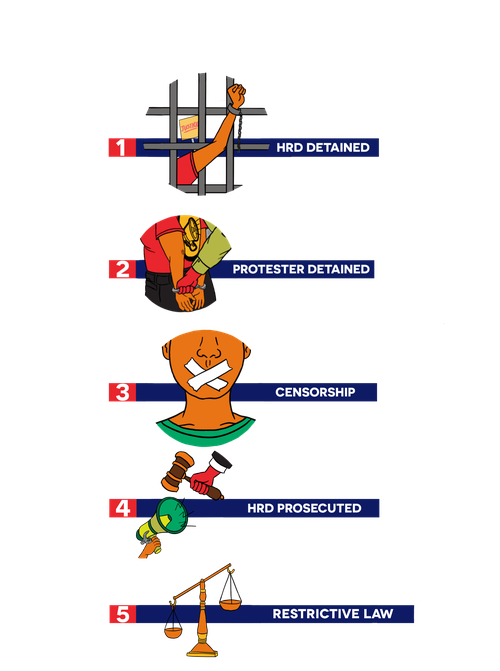

The main civic space violations documented in Asia and the Pacific over the past year are the arbitrary detention of protesters and the use of excessive force by security forces against peaceful protests. Another widespread trend was the detention of HRDs and the use of an array of restrictive laws and trumped-up charges to prosecute them. Governments also used censorship in many countries in the region to silence expression, block criticism of those in power and deny people access to information.

Arrests of human rights defenders

Authorities detained HRDs in at least 15 Asian and Pacific countries. Many were criminalised under anti-terrorism, criminal defamation, national security and public order laws. In some cases, there were reports of deaths, ill-treatment and torture in custody. There are also increasing concerns about transnational repression leading to the detention of HRDs.

The detention of HRDs remains widespread in China, with scores detained and prosecuted in secret trials under broad and vague provisions such as ‘picking quarrels and stirring up trouble’ and ‘subversion of state power’, including citizen journalist Zhang Zhan, filmmaker Chen Pinlin and human rights lawyer Xie Yang. Some were subjected to torture or ill-treatment. In Hong Kong, dozens of pro-democracy activists have been criminalised under the draconian 2020 National Security Law and the 2024 Safeguarding National Security Ordinance, including human rights lawyer Chow Hang-Tung and media owner Jimmy Lai. The authorities have also continued to carry out transnational repression by issuing warrants, offering bounties, cancelling passports and prosecuting family members of Hong Kong activists in exile. Meanwhile in Laos, lawyer Lu Siwei was convicted for 'illegally crossing the border' in May 2025 after being detained.

HRDs have been criminalised in numerous Southeast Asian countries. They have been systematically detained in Vietnam and prosecuted on trumped-up charges of ‘abusing democratic freedoms’ and ‘spreading propaganda against the state’ for their peaceful expression, including journalist Truong Huy San, land rights defender Trinh Ba Phuong and lawyer Tran Dinh Trien. In Cambodia, incitement charges have been the weapon of choice to criminalise activists, including environmental HRD Ouk Mao and labour and political activist Rong Chhun, while five environmental activists from the Mother Nature movement remain behind bars. The Cambodian government has also engaged in transnational repression by pursuing HRDs across borders in Malaysia and Thailand. Thai authorities have used article 112 of the Criminal Code that criminalises criticism of the monarchy, known as the lèse-majesté law, to detain and convict scores of HRDs for speaking out. Courts routinely deny bail to people charged with the offence. Among those criminalised is human rights lawyer Arnon Nampa, who has now had 10 convictions and has been sentenced to a total of 29 years in jail for his activism. He faces four more trials.

been sentenced to a total of 29 years in jail for his activism. He faces four more trials.

The military junta in Myanmar has detained HRDs in various prisons across the country on fabricated charges since its 2021 coup. In May 2025, journalist Than Htike Myint was sentenced to five years in prison on terrorism charges. Many HRDs are held in solitary confinement and have faced systematic torture and ill-treatment, with some dying in detention due to a lack of medical care. In July 2025, student activist Ma Wut Yee Aung died in the notorious Insein Prison from injuries reportedly sustained during torture while under interrogation by the junta.

In the Philippines, HRDs including Indigenous activists have been detained on trumped-up charges of murder and terrorism financing while Salome (Sally) Crisostomo Ujano, a WHRD accused of rebellion, is serving a minimum 10-year sentence. Eight detained activists, including Delpedro Marhaen, are facing six-to-12 years’ imprisonment in Indonesia for simply expressing their opinions and posting on social media in support of the August 2025 Gen Z-led protests triggered by the government announcement of a housing allowance for lawmakers. The activists are accused of inciting violence.

HRDs in South Asia have also been detained and criminalised. In Pakistan, there has been a systematic and a relentless crackdown on activists from the Baloch ethnic group who are demanding accountability, justice and an end to enforced disappearances. The Counter Terrorism Department has detained scores of people, including Mahrang Baloch, central leader of the Baloch Yakjehti Committee, a human rights group. Authorities have also detained journalists.

In India, six HRDs accused of involvement in communal violence in Bhima Koregaon in 2018 remain detained under the draconian Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, an anti-terrorism law. Kashmiri HRD Khurram Parvez, arrested in 2021 under the same law, is in detention in a maximum-security prison in Delhi in reprisal for his human rights work.

In Afghanistan, the Taliban have continued to detain and persecute HRDs, including academics and cultural and education activists. In February 2025, Taliban officials arbitrarily arrested education activist Wazir Khan at his home in Kabul. They tied his hands, blindfolded him and took him to the General Directorate of Intelligence. There has also been a relentless crackdown on journalists, with dozens detained and ill-treated. Taliban intelligence agents arrested Sulaiman Rahil, director of Radio Khushal, in Ghazni province in May 2025 after he reported on impoverished women, sentencing him to three months in jail.

Across Asia Pacific, people mobilised to call for democratic reforms and human rights, demand better public services and an end to corruption, urge climate and environmental justice and show solidarity with Palestine. In response, states deployed their security forces to arrest and detain protesters in at least 18 countries.

In Southeast Asia, Indonesian authorities severely cracked down on protests. In March 2025, police used arrests and excessive force against tens of thousands of activists, members of labour groups and students who took part in a nationwide protest against the controversial military law revisions. According to the Advocacy Team for Democracy, the military and police were identified as the primary perpetrators of violence. A total of 161 people were arbitrarily detained during the protests. A further brutal crackdown was unleashed against the August 2025 mass protests. According to human rights groups, over 3,000 protesters were detained, including children. Some were denied access to adequate legal assistance and coerced and intimidated into signing official statements.

In the Philippines, tens of thousands took to the streets in September 2025 to protest against government corruption after it was alleged taxpayers had lost billions of dollars in bogus flood relief projects. Human rights groups reported that police used excessive force, arbitrarily arrested and detained over 200 people, including 91 children, and denied those arrested access to lawyers and their families. Police filed a range of charges against the detainees under the dictatorship-era Public Assembly Act 1985, long criticised for curtailing the right to protest.

Three student activists were detained in Malaysia in June 2025 and investigated under the Sedition Act for a protest in Sabah state, aimed at pressuring the prime minister to act against corrupt politicians. In September 2025, police detained a group of around seven Palestine solidarity protesters who had gathered near the US embassy in Kuala Lumpur.

In Timor-Leste in September 2025, at least twelve 12 students were arrested and detained for hours after police fired teargas at people protesting against a plan to buy new cars for lawmakers.

Authorities also detained protesters across South Asia. In Pakistan, there are ongoing restrictions on protests by Baloch activists. In January 2025, Karachi police obstructed and arrested activists ahead of a peaceful demonstration in Sindh province. In March 2025, prominent members of Baloch Yakjehti Committee were arrested during a peaceful protest in Quetta. That same month, at least six activists were detained following a protest in Karachi for disregarding a blanket ban on assemblies. In February 2025, Pakistan police arrested multiple opposition members ahead of a planned protest by jailed former prime minister Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party to mark the first anniversary of national elections PTI supporters say were rigged to benefit establishment parties. In July 2025, an anti-terrorism court sentenced eight PTI members to 10 years in jail for inciting protests outside military sites in 2023.

In India, at least nine student protesters remain in custody, including Gulfisha Fatima and Umar Khalid, for participating in 2020 protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, which discriminates against Muslims. They have been held in custody for around five years on terror charges and their trial has yet to start. In Sri Lanka in March 2025, police arrested 27 student activists in Colombo for protesting against the recruitment process for civil service jobs, while some protesters detained during the 2022 mass Aragalaya protests that forced a change of government remain in custody. In the Maldives, there have been continued reports of opposition protesters and youth activists facing arrest and excessive force.

In China, solo protester Peng Lifa was sentenced to nine years jail in July 2025 for peacefully expressing his dissent about the government’s COVID-19 lockdown and the anti-democratic rule of President Xi Jinping in October 2022. He was forcibly disappeared for more than two years after being detained. Police arrested at least 12 people in Hong Kong to block any form of protest or vigil on the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square Massacre in June 2025.

A University of Bristol study showed that Australian police are world leaders at arresting climate and environmental protesters. According to the study, over 20 per cent of all climate and environment protests involved arrests, more than three times the global average. In June 2025, five people were arrested during a Palestine solidarity protest in Sydney against an Australian company supplying arms to Israel. Ill-treatment by the police was also reported.

Censorship of critical voices

Another key civic space concern in the region is the use of censorship by governments, documented in at least 14 countries. Over the year the authorities used their powers to restrict access to information critical of the state by blocking news portals and social media platforms, imposing internet shutdowns and banning publications.

China employs one of the most sophisticated censorship regimes in the world, which it uses to block access to blogs, social media platforms and websites critical of the Chinese Communist Party. North Korea’s totalitarian regime continues to block access to foreign media, particularly from South Korea. Punishments for accessing or distributing such media include jail, forced labour and the death penalty.

In Southeast Asia, Singapore has rampant censorship. The Protection against Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act is a sweeping law that permits a single government minister to declare that information posted online is false and order the content’s ‘correction’ or removal if deemed to be in the public interest. The government used the law in January 2025 to block access to the Australia-based academic website East Asia Forum following an article it published on Singapore. In April 2025, the government ordered Facebook owner Meta to block Singaporeans’ access to posts made by foreigners ahead of the national election. In June 2025, a theatre production was cancelled for highlighting issues ‘contrary to national interest’.

In Malaysia, the government has continued to use the Printing Presses and Publications Act 1984 to ban books to ‘prevent the spread of beliefs, ideologies or movements that could compromise security, public order and social harmony’. They include books with LGBTQI+ characters and themes and books considered religiously deviant.

In Vietnam, authorities banned a May 2025 print edition of The Economist, which featured the country’s top leader on its cover, while in the Philippines, a documentary depicting the harassment of Filipino fishers in the West Philippine Sea was pulled two days before its scheduled premiere, raising concerns that political pressure may have played a role.

In January 2025, a punk rock band in Indonesia, Sukatani, had to issue a public apology and withdraw their song about police corruption from online platforms. Many believe the police had put pressure on them to do so. The Indonesian authorities also sought to restrict coverage of the August 2025 protests, with the broadcasting commission issuing a circular to media not to broadcast anything that could tarnish the government’s image. Authorities further disrupted internet access, including the suspension of TikTok’s livestream feature, which had become a vital tool for documenting protests in real time.

In April 2025, a Thailand court of appeal upheld a lower court order from 2022 to block and remove 52 URLs under Section 20 of the Computer Crime Act, including the website www.no112.org, which was used to collect signatures for a petition to repeal the lèse-majesté law. It found that the content, which advocates for the repeal of Criminal Code article 112, violated morality and public order by undermining the monarchy.

Censorship was also documented in South Asia. In July 2025, a judicial magistrate in Pakistan, acting on a request from the National Cyber Crime Investigation Agency, ordered YouTube to block 27 channels, including those of reporters Matiullah Jan and Asad Toor and the PTI’s official channel, along with those of several other political commentators. In May 2025, YouTube told exiled investigative journalist Ahmad Noorani it had blocked his channel, which has 173,000 followers, in Pakistan based on a legal complaint from the government. Internet shutdowns have been imposed around opposition rallies.

In India in April 2025, following a militant attack in Kashmir, authorities blocked social media accounts and YouTube channels. The government also ordered the blocking of the 4PM News Network YouTube channel, citing national security and public order concerns, following its coverage of the anti-war movement. In May 2025, authorities ordered the blocking of over 8,000 social media accounts on X/Twitter, including those of the Kashmir-based news outlets Free Press Kashmir, The Kashmiriyat and Maktoob Media, which focuses on human rights and minorities.

In July 2025 came reports that the Indian government had ordered X/Twitter to block 2,000-plus accounts, including two Reuters News accounts, while in August 2025, authorities banned 25 academic and journalistic books on Kashmir. These books addressed abuses in Kashmir and the region’s political journey over the decades.

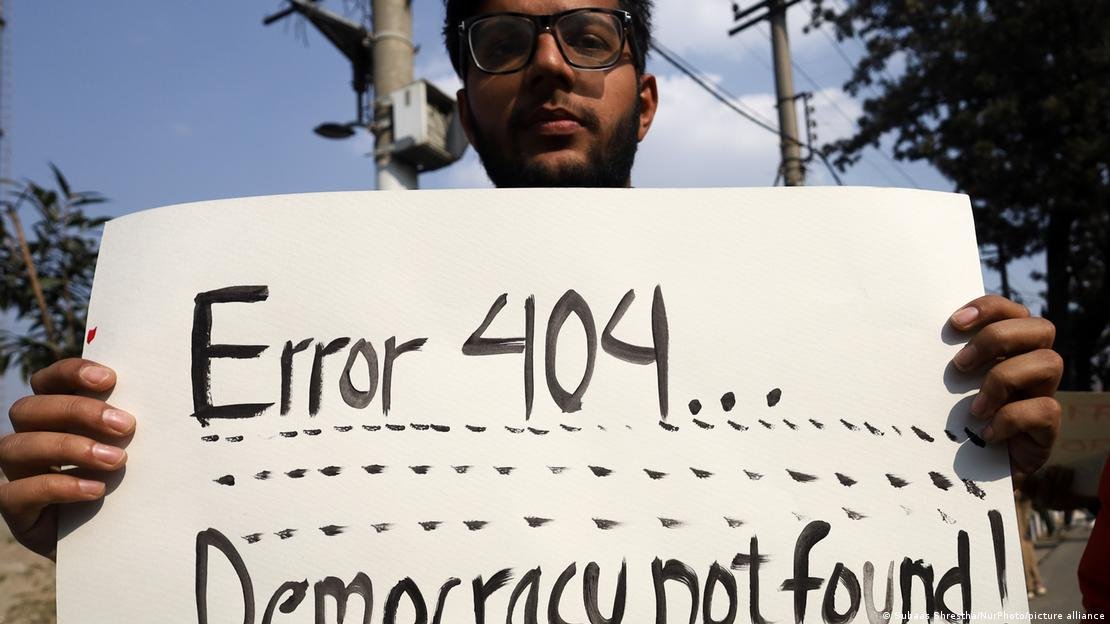

In Nepal in July 2025, the Nepal Telecommunications Authority instructed service providers to block Telegram, claiming the move was aimed at combating online fraud and money laundering. The government’s sweeping ban on 26 social media platforms, imposed in September 2025, was the spark for mass Gen Z-led protests that brought a brutal response from the state that left 76 people dead before forcing the prime minister’s resignation.

Taliban authorities in Afghanistan enforce stringent control over media content, effectively limiting the dissemination of information to state-approved narratives. Media outlets have been suspended or closed and women journalists arrested or fired.

In the Pacific, online defamation laws create a chilling effect and have been used to criminalise critics and HRDs who speak out. Journalists also face challenges in their reporting, including restrictions against accessing information and online abuse and threats. In Papua New Guinea, journalist Culligan Tanda was sacked for featuring an opposition parliamentarian on his show while in Samoa, Lagi Keresoma was charged with criminal defamation in May 2025 after reporting on a police officer. In Vanuatu, the government monitors news outlets to ensure content does not contradict its messaging while Nauru imposes a high fee for international media personnel intending to visit the country. Environmental activists remain at risk of strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs), legal actions intended to tie civil society up in lengthy and expensive legal processes.

Countries of concern: Indonesia and Pakistan

An ongoing regression of civic space is underway in Indonesia. Over a year into the administration of President Prabowo Subianto, serious concerns have been raised about efforts by the authorities to restrict civic space and silence dissent. Scores of HRDs have faced arrest, criminalisation, intimidation, physical attacks and surveillance. There are also concerns about the government’s brutal crackdown on protests with impunity, particularly in March and August 2025. The media has faced threats and attacks, including while covering protests, and the government has continued to repress activism in the Papua region, where there are longstanding grievances against systematic abuses by the security forces and exploitation of resources.

Another country of concern is Pakistan, where the criminalisation of HRDs and journalists, an ongoing crackdown on human rights movements and protests and digital restrictions continue to escalate. There has been a systematic crackdown on Baloch activists since March 2025, with many detained and facing baseless charges. The government has also banned the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement, a movement that has mobilised nationwide to advocate for the rights of the Pashtun ethnic minority. Journalists remain at risk, with many facing charges under the draconian Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act for their reporting. Authorities have blocked social media apps and YouTube channels of journalists and the opposition and there has been a crackdown on protests by the PTI, with many prosecuted.

Protests repressed

Protesters were detained in at least 22 countries in the Asia Pacific region. In addition, in at least 10 countries, security forces used excessive force, leading to injuries and in some cases unlawful killings. Journalists and protest observers were targeted in some instances. Among the protesters targeted were those calling for democratic reforms, environmental rights, Indigenous rights, labour rights, accountability, equality, justice and end to the human rights violations in the OPT.

The crackdown on protests is particularly strong in South Asia as governments have sought to stifle the opposition, ethnic minorities and students, among others. In Pakistan, the government severely cracked down on the opposition around the February 2024 election, particularly protesters linked to Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party. Scores of protesters were attacked with batons and sticks and arbitrarily detained by the police across the country. In May 2024, police met protests against rising costs in Pakistan-administered Kashmir with arrests and teargas while in July 2024, hundreds were detained in response to a march seeking to raise awareness of human rights concerns in Balochistan, with excessive force used to prevent protesters reaching the port city of Gwadar.

In Bangladesh, hundreds were detained as part of a brutal crackdown on the mass student-led protests in July 2024 that ultimately brought down the Sheikh Hasina regime. At least 600 people were killed by security forces and by the Awami League’s student wing. Others suffered torture and ill-treatment in detention. Firearms, teargas, stun grenades, rubber bullets and shotgun pellets were used to disperse protesters, injuring many.

In Sri Lanka, police cracked down on opposition protests over rising costs and protests by students from the Inter-University Students’ Federation and teachers. In February 2024, security forces shot teargas and fired water cannon at Tamil students from Jaffna University who protested at the government’s failure to resolve issues faced by people in east and north Sri Lanka. Some were arrested and ill-treated. A crackdown on protests, particularly by pro-monarchy groups, was also documented in Nepal, with arbitrary arrests and excessive force.

In India, farmers from Haryana Punjab and Uttar Pradesh states who protested to demand support from the government in February 2024 were met with excessive police force to stop them entering Delhi. More than 100 protesters were injured. The government also blocked roads with heavy barricades, iron nails and barbed wire and deployed drones to drop teargas shells on protesters.

| COUNTRY | SCORES 2025 | 2024 | 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 |

| AFGHANISTAN | 8 | |||||||

| AUSTRALIA | 76 | |||||||

| BANGLADESH | 29 | |||||||

| BHUTAN | 51 | |||||||

| BRUNEI DARUSSALAM | 30 | |||||||

| CAMBODIA | 27 | |||||||

| CHINA | 10 | |||||||

| FIJI | 65 | |||||||

| HONG KONG | 16 | |||||||

| INDIA | 30 | |||||||

| INDONESIA | 42 | |||||||

| JAPAN | 88 | |||||||

| KIRIBATI | 85 | |||||||

| LAOS | 5 | |||||||

| MALAYSIA | 50 | |||||||

| MALDIVES | 50 | |||||||

| MARSHALL ISLANDS | 90 | |||||||

| MICRONESIA | 90 | |||||||

| MONGOLIA | 59 | |||||||

| MYANMAR | 10 | |||||||

| NAURU | 59 | |||||||

| NEPAL | 48 | |||||||

| NEW ZEALAND | 92 | |||||||

| NORTH KOREA | 2 | |||||||

| PAKISTAN | 24 | |||||||

| PALAU | 90 | |||||||

| PAPUA NEW GUINEA | 54 | |||||||

| PHILIPPINES | 38 | |||||||

| SAMOA | 82 | |||||||

| SINGAPORE | 30 | |||||||

| SOLOMON ISLANDS | 69 | |||||||

| SOUTH KOREA | 73 | |||||||

| SRI LANKA | 37 | |||||||

| TAIWAN | 88 | |||||||

| THAILAND | 34 | |||||||

| TIMOR-LESTE | 72 | |||||||

| TONGA | 71 | |||||||

| TUVALU | 88 | |||||||

| VANUATU | 69 | |||||||

| VIETNAM | 13 |