On 10th November 2019, a journalist and a videographer from Paceñísima TV were attacked while covering pro-Morales protests in Ceja de El Alto, a town bordering La Paz. Bolivia’s National Press Association (ANP) reported that a group of Morales supporters attacked journalist Isabel Poma, pulling her hair and throwing her to the ground, beating and kicking her. Poma was bruised on her arms and legs, and her injuries caused a nosebleed. Videographer Juan Pardo was beaten with a stick and received death threats. The assailants also burnt the journalists’ microphone and cable, and took their camera.

In addition, on 10th November 2019, the IACHR’s Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression, Edison Lanza, said on Twitter that the organisation had received several reports of attacks on journalists and the press in Bolivia, perpetrated by both government supporters and members of opposition movements. According to Lanza, the IACHR received information that anti-Morales groups had occupied public communications channels and cut their transmission.

On 14th November 2019, the Asociación Nacional de la Prensa de Bolivia (Bolivian National Press Association - ANP) reported that from 20th October 2019, 76 journalists and 14 press outlets had been subjected to attacks in Bolivia.

On 19th November 2019, the IACHR stated that during the post-electoral protests, they received reports of restrictions on the work of journalists and the press. According to the IACHR, press workers in Bolivia have been under pressure, some television channels received threats of closure, and radio stations were reportedly set on fire. In addition, the organisation recalled that the State has a duty to ensure the security of journalists and communicators who are covering demonstrations, so that they are not detained, threatened, attacked or limited in the exercise of their work.

Foreign correspondents face hostility and attacks

Lizárraga afirma que procesará a periodistas o seudoperiodistas que incurran en sedición | Urgentebo https://t.co/X4Upp4Y4Tm

— urgentebo (@Urgentebo) November 15, 2019

In November 2019, several foreign correspondents were threatened and attacked while reporting on the situation in Bolivia.

Reporter Mariano Garcia, with Argentinian Telefe channel, stated that the aggression against them began after they interviewed Luis Fernándo Camacho on 12th November 2019. On 13th November 2019, a reporter from another Argentinian channel had a verbal altercation with a Bolivian woman while reporting live. A number of people gathered around the film crew and a man was filmed smacking the camera down.

On 14th November 2019, Communication Minister Roxana Lizárraga, appointed by Bolivia’s interim president Jeanine Áñez, accused some foreign and Bolivian “journalists or pseudo-journalists” of causing sedition. Lizárraga said that these journalists had been identified and that the Minister of Government would take action against them.

On the same day, aggression escalated. While filming a live report from La Paz for Argentinian TV Channel Todo Noticias, journalist Carolina Amoroso was interrupted and followed by passersby shouting, “go back to your country!” and “get out, liars!”. The moment was caught on camera, with the film crew eventually surrounded by people shouting. Later, the same journalists faced hostility while covering a pro-Morales protest. Journalists from América Noticias, Telefe and Crónica TV also reported facing hostility and attacks from protesters from both camps in the political crisis. According to El País, protesters threatened to set fire to a crew of reporters, throwing stones and following them when they returned to their hotel. Telefe’s Mariano Garcia claimed that, later in the day, he and other Argentinian journalists were warned that security cameras around their hotel had been broken by a group intending to attack them. Besieged, the journalists requested the help of diplomatic authorities. They were evacuated to their country’s embassy and returned to Argentina the following day.

On 15th November 2019, Al Jazeera correspondent Teresa Bo was tear-gassed while covering a protest in La Paz. A video of the incident shows a police officer intentionally gassing the reporter in the face while she was on air.

Also on 15th November 2019, the IACHR’s Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression expressed alarm at the comments made by Minister Lizárraga, stating that state officials should not stigmatise the press.

Self-censorship

In November 2019, at least two newspapers working in Cochabamba, Los Tiempos and Opinión Bolivia, announced temporary self-censorship measures for security reasons. Los Tiempos opted to cancel the circulation of their print edition temporarily following threats to its journalists. According to news sources, two other state-owned communication outlets also stopped transmitting their regular programming due to threats.

On 4th December 2019, Alejandro Salazar (Al-Azar), graphic editorialist for La Razón de La Paz newspaper, suspended the publication of his illustrations due to harassment, including threats, he has received on social media for the political content of his work.

Decree to restore freedom of expression

On 10th December 2019, Bolivia’s Communication Minister announced that the government would introduce legislation to restore freedom of expression in Bolivia and guarantee the rights of press workers. The Asociación Nacional de la Prensa de Bolivia (Bolivian National Press Association - ANP) saluted the initiative and highlighted that it is essential to re-establish guarantees on the work of the media and journalism in the country.

Association

On 7th November 2019, the mayor of Vinto, in the Cochabamba province, was dragged barefoot through the streets by protesters, who also covered her in paint, forcibly cut her hair and forced her to sign a resignation letter. According to a report by the BBC, angry protesters in a demonstration against the election results marched on the town hall after rumours spread that two demonstrators had been killed in clashes with Morales loyalists. The protesters accused mayor Patricia Arce, of Morales’ MAS party, of bussing Morales supporters into town and blamed her for the deaths. In addition to the attack against Arce, the town hall building was also vandalised in the protest. According to news reports, two unidentified men retrieved Arce from the crowd after several hours and delivered her to a police officer.

Military discretion in responding to protests

On 14th November 2019, Bolivia’s interim government published a decree (Decreto Supremo 4078) granting the military broad discretion in the use of force to contain protests. Human rights organisations and international organisations argued that this directive was not in line with international law and standards, calling on authorities to urgently repeal it. According to Amnesty International, the decree would allow potential human rights violations to go unpunished by exempting from criminal responsibility armed forces personnel participating in operations to re-establish internal order and public security. Despite the outcry, the decree remained in place until 28th November 2019. In this period, there were multiple reports of excessive use of force by the police against protesters.

Massacres in Sacaba and Senkata

Confirmamos que 8 personas fallecieron en #ElAlto tras el operativo policial-militar en la planta de #Senkata por impacto de proyectil de arma de fuego. Anunció que hará seguimiento a la investigación que inició de oficio el Ministerio Publico.https://t.co/4KYbpN25SM

— Defensoría Bolivia (@DPBoliviaOf) November 21, 2019

Recibimos información grave sobre sucesión de agresiones a medios y periodistas en Bolivia. Tanto de partidarios del gobierno y mov. oposición. Estos últimos habrían ocupado medios públicos y cortado la transmisión. Ayer la retención de reportero por la policía en La Paz (1/2)

— Edison Lanza (@EdisonLanza) November 10, 2019

On 16th November 2019, the Associated Press reported that at least five protesters were killed in the town of Sacaba after security forces fired on pro-Morales demonstrators. According to witnesses, violence began after the protesters, mainly coca-leaf growers, tried to cross a military checkpoint to enter the city of Cochabamba. While the security forces stated that the protesters were armed, protesters claim that the police opened fire indiscriminately on a crowd.

On 19th November 2019, at least eight people were killed in El Alto during confrontations when military forces acted to unblock access to the Senkata fuel plant that had been blockaded by Morales loyalists. Defence Minister Fernando López stated on television that the demonstrators were “terrorists” acting to damage Bolivia, its people and strategic corporations. Local witnesses accused the armed forces of a massacre. An initial investigation confirmed that the victims in Senkata were killed by firearms.

IACHR report on Bolivia and independent group to investigate abuses

On 12th November 2019, several civil society organisations in Bolivia sent a letter to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) urging the organisation to conduct an “in loco” visit to Bolivia.

On 19th November 2019, the IACHR condemned the Bolivian military’s excessive use of force in the context of social protests and urged Bolivia to repeal decree 4078. The organisation began a technical visit to Bolivia on 23rd November 2019, meeting with government authorities, civil society representatives, journalists, injured protesters and others affected by the political crisis. On 10th December 2019, IACHR published preliminary findings on its visit, stating that their delegates found serious indications of extrajudicial killings in both Sacaba and Senkata. The organisation called for an autonomous international investigation into alleged human rights abuses.

Although Bolivia’s interim government rejected the report, saying it was unfair and inaccurate, on 12th December 2019 the Bolivian government and the IACHR signed an agreement to create a mechanism to support investigations into human rights violations. An Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts will be tasked with planning and assisting investigations, proposing measures to ensure the safety of those involved, and making recommendations toward plans to assist victims.

Expression

Attacks on journalists during political crisis

Una turba de masistas quemó y destruyó mi casa, mi familia y yo nos encontramos bien y en un lugar seguro. Esta acción criminal demuestra el carácter violento y delincuencial del Movimiento al Socialismo. Esto no me acallara, seguiré denunciando las injusticias y la corrupción pic.twitter.com/Y3Zo6nUoWq

— Waldo Albarracin (@w_albarracin) November 11, 2019

On 10th November 2019, human rights defender and Universidad Mayor de San Andrés rector Waldo Albarracín’s house was looted and set on fire with his family inside. According to a report by CSO Frontline Defenders, a mob of around 500 people approached Albarracín’s house, which prompted the family to evacuate immediately. Two of the defender’s children were cornered until they managed to escape and take refuge in a neighbour’s house. A day before, on 9th November 2019, public servants linked to former president Morales had allegedly made a public call for the activist and other social leaders to leave the La Paz department for causing “upheaval, violence and division”. In October 2019, Albarracín sustained slight cranial injuries after being struck in the face with a tear gas cannister during a protest. Since then, he has received messages on social media containing death threats to him and his family.

On 28th November 2019, a group of civil society organisations from Argentina travelled to Bolivia to document complaints of human rights violations in the political crisis which erupted following Bolivia’s general elections in October 2019. The “Solidarity with Bolivia” delegation denounced that its members were detained and threatened during the course of their visit. A group of people assaulted the members of the group when they arrived and, according to the delegation, 14 members of the group were interrogated by security forces at Viru Viru Airport. Hours after the delegation’s arrival, the interim government’s Minister of Interior, Arturo Murillo, publicly stated, “We recommend that the foreigners who are arriving in our country as these seemingly harmless subjects should be cautioned, we are watching them, we are following them”.

Protesters kidnapped the mayor of a small town in central Bolivia, forcibly cut her hair, drenched her with red paint, made her sign an improvised resignation letter, then marched her through the streets barefoot, witnesses said https://t.co/uEZcXCGdx5

— The New York Times (@nytimes) November 8, 2019

On 10th November 2019, Evo Morales resigned as president of Bolivia, after weeks of unrest over contested general elections at the end of October 2019. Shortly beforehand, the commander-in-chief of Bolivia’s armed forces had publicly withdrawn his support and urged Morales to step down. Within hours, several key political officials in the line of succession, including the vice-president, and the Senate and Chamber of Deputies leaders, also resigned. In the days that followed, violent confrontations between government loyalists and opponents escalated, with reports of widespread looting and of barricades in La Paz. In a transition negotiated under pressure, the Senate’s second vice president, Jeanine Añez, emerged as interim president on 12th November 2019. Previously an opposition senator, Añez quickly replaced cabinet ministers and other high officials.

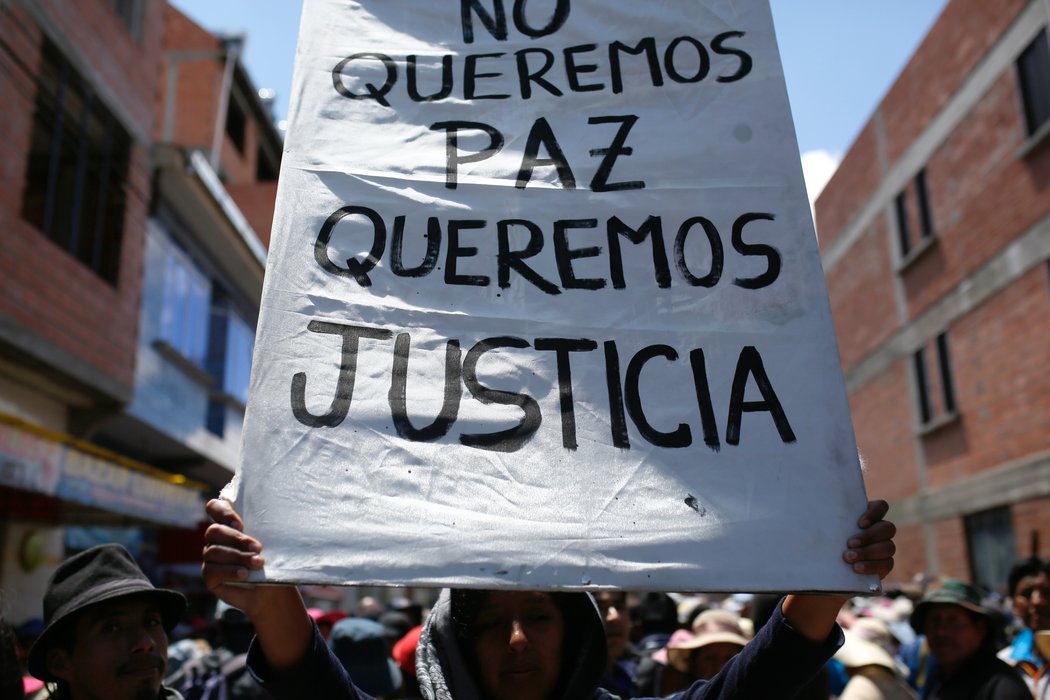

Violence has continued with clashes between security forces and Morales supporters, as well as between demonstrators across the political spectrum. As the interim government sought to re-establish order, there have been continued reports of repression of protests and attacks against the press. Between 20th October and 27th November 2019, at least 36 people were killed and 804 injured in the unrest.

In early January 2020, an election tribunal set 3rd May 2020 as the date for new general elections. Further information on incidents related to freedoms of association, peaceful assembly and expression is detailed below.

Peaceful Assembly

Violent protests