In November 2020, Brazil held countrywide local elections to elect city councillors and mayors. Politically-motivated attacks and assassinations increased by nearly 200 percent in 2020 in comparison to previous years. According to research by civil society organisations Terra de Direitos and Justiça Global, an attack or murder was registered every three days. A survey identified 13 killings and 14 attacks on the lives of elected representatives, candidates and pre-candidates between 1st January and 1st September 2020. This violence increased even more as elections approached, with 14 murders and 66 attacks taking place between 2nd September and 29th November 2020.

Association

Avá-Guarani peoples threatened and leader detained

O cacique Crídio Medina, do tekoha Guasu Guavirá, foi preso acusado de acobertar um “crime”. Após a colheita de milho, as crianças da aldeia recolheram espigas que restaram no solo, não acessadas pela colheitadeira. O fazendeiro prestou queixa por furto. https://t.co/kZQBwJ7Z9i

— Cimi (@ciminacional) August 28, 2020

On 26th August 2020, cacique (chief) Crídio Medina, Indigenous Avá-Guarani leader of the Ywyraty Porã village in Paraná state, was detained and later charged with theft. According to the Conselho Indigenista Missionário (Missionary Council for Indigenous Peoples - CIMI), police accused him of “covering up” for the village’s children who allegedly stole corn from a nearby farm. Members of the community said the children acted innocently in collecting corn that was left on the ground and not reaped by the combine harvester, which is usually discarded. The leader was released after two days, but reportedly still faces criminal charges.

In September 2020 CIMI, with other civil society organisations Justiça Global and Articulação dos Povos Indígenas (Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil - APIB), sent letters to the United Nations and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) about the case, saying that the arrest was not only unwarranted but also exposed the Indigenous community to COVID-19. The organisations also filed a request with Brazilian authorities to investigate potential racism and abuse of authority in the arrest, as the chief was held for two days without communication with his family or community. The Avá-Guarani people have been suffering a series of attacks due to racism, discrimination and the lack of recognition of the territorial rights of Indigenous peoples.

Landless Workers’ Movement leader killed

On 25th October 2020, Ênio Pasqualin, a leader of Movimento Sem Terra (Landless Workers' Movement - MST), was found dead. As reported by MST, Pasqualin had been kidnapped the day before from the house where he lived with his family in the Ireno Alves dos Santos settlement, Rio Bonito do Iguaçu municipality in the south of Paraná. He was executed with gunshots and his body was found near the settlement. MST called for a thorough investigation and demanded justice for Pasqualin’s murder. At the end of November 2020, news outlets reported that three suspects had been arrested and the investigation concluded. According to information provided by the police, an intellectual author had had a dispute with Pasqualin over land distribution in the region.

Two indigenous leaders receive international prizes

In a positive development, in 2020 two Brazilian women human rights defenders were recognised internationally for their work:

Alessandra Korap Munduruku was awarded the 2020 Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights prize for her work defending the rights, ancestral lands and culture of Indigenous peoples. Alessandra has fought against the construction of hydroelectric dams on the Tapajós River and against illegal mining infringing upon Munduruku territory. She has been an advocate for the demarcation of Indigenous lands and for Indigenous communities’ right to be consulted on decisions that affect their territories. She has also played a crucial role in advancing the leadership of women in the Munduruku community and among other Indigenous peoples of Brazil through her involvement in the Wakoborûn Indigenous Women’s Association and the Pariri Indigenous Association.

Osvalinda Marcelino Alves Pereira received the Edelstam Prize 2020 for outstanding contributions and exceptional courage in standing in defence of human rights. She is a small-scale farmer living in a settlement surrounded by forests in Trairão, a small town in Pará state, at the heart of the Amazon. She is a rainforest defender and community organiser who has put herself at great risk in defending the forest and its population. For nearly a decade, she and her husband have received numerous threats from criminal networks in the state.

Due to these threats, they spent over 18 months in hiding with the support of Brazil’s Federal Program to Protect Human Rights Defenders, Journalists and Environmental Defenders. Now they are back in Pará to continue their work and Osvalina said they will not give up: “My husband and I will continue defending the agriculture, nature and forest because this is our home”. She also said:

“This award shows we are not alone. It shows that our fight is not in vain and people around the world care about our distress and our struggle.”

Control of CSOs in the Amazon

On 9th November 2020, newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo reported that Brazil’s government was discussing creating a regulatory framework through the National Council on the Legal Amazon to promote the control of non-governmental organisations working in the Amazon rainforest region. The body, led by Vice-President Hamilton Mourão, would then be able to limit institutions which government authorities believe violate “national interests”. After European Union parliamentarians sent a letter rejecting the proposal, Mourão denied that the government had such intentions and claimed that newspapers had misinterpreted the Council’s documents.

However, civil society organisations in the Pacto Pela Democracia coalition published a letter in response to the EU parliamentarians, highlighting the many occasions in which the government curtailed civil society participation, vilified and threatened CSOs and activists. Environmental defenders have been frequently targeted by attacks and harassment. In October 2020, for instance, Environment Minister Ricardo Salles filed a petition asking a judge to subpoena the executive secretary of climate coalition Observatório do Clima, Marcio Astrini, to explain statements he made in an interview on the government’s environmental policy.

Peaceful Assembly

Popular outrage after Black man beaten to death

Está acontecendo agora um ato no Carrefour da Barra da Tijuca, no Rio de Janeiro em repúdio ao assassinato de João Alberto em Porto Alegre. Manifestantes ocuparam e fecharam a loja. pic.twitter.com/ZVYAxriKGY

— Alma Preta (@Alma_Preta) November 20, 2020

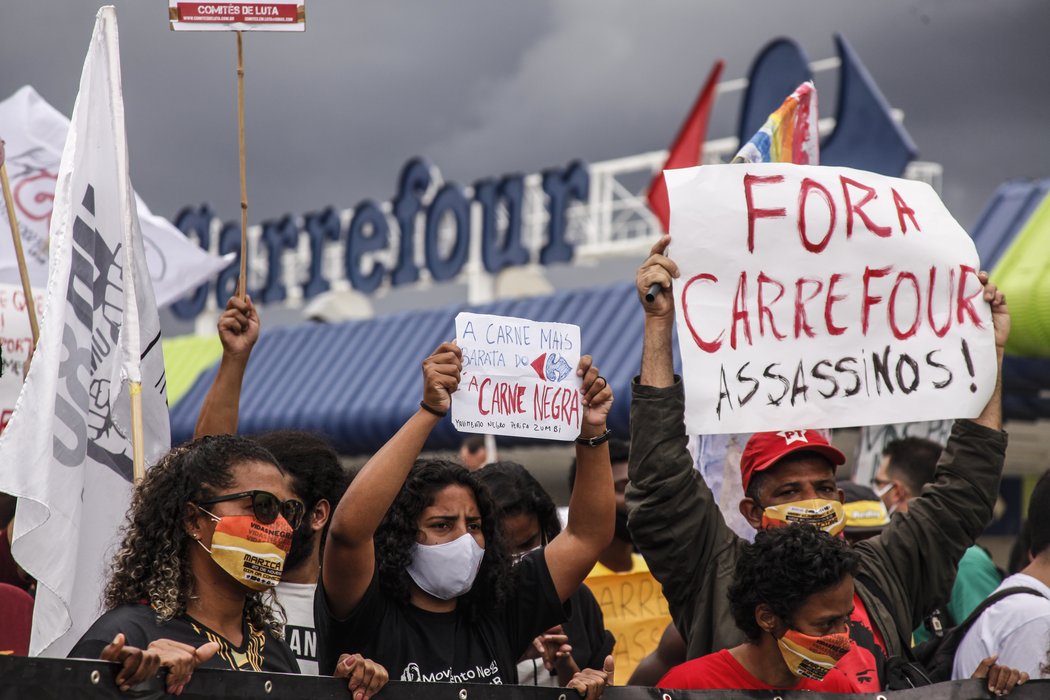

Protests erupted in major cities across the country after a Black man, Beto Freitas, was beaten to death by private security guards in Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul state. Footage of the brutal killing of 40-year-old Freitas, in the parking lot of a Carrefour supermarket on 19th November 2020, was widely shared online and sparked outrage. The violence took place on the eve of Brazil’s Black Awareness Day, when the country’s Black movements typically march and organise events.

Demonstrations took place in front of the Carrefour store in Porto Alegre and in other major cities such as Rio de Janeiro and Brasília. In São Paulo, the 17th Black Consciousness March brought thousands to the streets and ended with a march toward a Carrefour store to demand justice for Beto. At the end of the protest, some demonstrators smashed the front window of the shop, scattered goods from shelves over the store’s floor and set fire to some products. In Porto Alegre, police officers fired tear gas to disperse demonstrators, who chanted “Black lives matter”.

The Carrefour group released a statement lamenting Freitas’ “brutal death”, saying it would end its contract with the private security company and temporarily close the store in Porto Alegre out of respect. Civil society network Coalizão Negra Por Direitos (Black Coalition for Rights) called for an investigation into the company’s practices and for accountability.

This is just one of many incidents of violence against Black Brazilians. According to the Violence Atlas 2020 developed by civil society organisation Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública (Brazilian Forum on Public Safety), Black and mixed-race people account for about 57 percent of Brazil's population and constitute 74 percent of victims of lethal violence. 79 percent of people killed by police are Black or mixed-race.

Expression

Intimidation of journalists covering COVID-19

#BRAZIL: Brazilian national TV channel Globo found that the office of Rio de Janeiro Mayor Marcelo Crivella used public funds to pay municipal employees to monitor and obstruct journalists at hospitals and block news crews from covering the COVID pandemic. https://t.co/4wLdYTlJMD

— CPJ Américas (@CPJAmericas) September 1, 2020

At the end of August 2020, national TV channel Globo aired an investigative report saying the office of Rio de Janeiro Mayor Marcelo Crivella used public funds to pay groups of municipal employees to monitor and obstruct journalists at local hospitals and block news crews from covering the COVID-19 pandemic. The municipal public servants coordinated shifts in front of the city’s hospitals on a WhatsApp group. They then reportedly acted to prevent recordings, intimidating journalists and interviewees and preventing criticism of municipal management of the pandemic. Several press organisations called for an investigation into the group, known as “Guardiões do Crivella” (Crivella’s Guardians), and the extent of public authorities’ involvement in sabotaging journalistic work.

In a separate development, on 2nd November 2020 a group of beachgoers in Florianópolis, Santa Catarina state, harassed and threatened NSC TV journalist Bárbara Barbosa and camera operator Renato Soder as they were preparing a report on non-compliance with local COVID-19 restrictions. One man slapped Barbosa’s hand as she held her phone, and a woman then grabbed the journalist’s phone while men took her wrists and restrained her, Barbosa told CPJ. The group threatened to break Soder’s camera and steal Barbosa’s phone unless they stopped filming and left the area. The journalist said she was scratched on the arm but did not have any other injuries.

Censorship

In August and September 2020, a series of judicial rulings censored investigative journalism in Brazil. On 25th September 2020, a city court in Rio de Janeiro ordered a digital news outlet to take down reports related to alleged corruption practices in investment bank BTG Pactual. On 4th September 2020, a judge prohibited news outlets from reporting on documents related to an investigation into corruption in the cabinet of senator Flávio Bolsonaro, son of president Bolsonaro. In early December 2020, the two anchors of Jornal Nacional, Brazil’s most watched television news programme, were subpoenaed by Rio’s police for allegedly disobeying the court’s order not to publish information on the case.

Journalists kidnapped, assaulted and threatened

On 21st October 2020, two assailants broke into the home of journalist José Airton Alves Júnior in Itarema, Ceará state, threatened him and beat him up. Alves Júnior told the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) that he could identify the two attackers, who have ties to a local official. They entered the journalist’s house, punched and kicked him and tried to drag him out of the house. The assailants reportedly also told Alves Júnior he should stop talking about the local official and that next time they would kill him. As reported by CPJ, they punched the journalist’s wife when she tried to intervene and fled when the family’s neighbours arrived to see what was happening.

Alves Júnior has covered local politics and general news at a variety of radio broadcasters since 1992 and currently runs the digital news media Portal Santana / Itarema. He told CPJ the attack may have been retaliation for a post on digital media highlighting ethical concerns related to the local official.

In a separate incident, on 26th October 2020 journalist Romano dos Anjos was kidnapped by unidentified men who broke into his home in the city of Boa Vista, Roraima state. The assailants tied up his wife and took the journalist in his car, which was later found burned on a roadway. According to news reports, the following morning a passerby found him tied up and blindfolded in the rural outskirts of Boa Vista. He had injuries on his legs and arms, as well as a fracture to his shoulder. Dos Anjos hosts a daily news show on TV Imperial, where he covers corruption, local crime and police. He also hosts a similar show on local radio station Radio Equatorial. His wife told CPJ she wasn’t aware of threats to the journalist, but that he had recently denounced irregularities in the local government’s use of COVID-19 pandemic resources.

Decline in freedom of expression

On 6th October 2020, the IACHR held a second public hearing on freedom of expression in Brazil, where a coalition of 14 civil society organisations presented information on the country’s situation. The organisations described violations of the right to information and the impact on the lives of Indigenous peoples, women, the Black population, children and adolescents, residents of favelas and peripheries, and the LGBTQI+ population. During the pandemic, the organisations said, Brazil’s marginalised and excluded populations have had their rights to freedom of expression, education and health seriously violated.

In response to complaints, said the participant organisations, the government stepped up hostility against the press. The situation is especially critical for women journalists, said Patrícia Campos Mello from Folha de S. Paulo who has been the target of a smear campaign by government supporters. She said:

“We are the target of defamation campaigns encouraged and amplified by the government. Since February this year, thousands of memes have circulated on the Internet in which my face appears in pornographic montages, calling me a prostitute and making allusions to sexual organs. I get messages from people saying that I offer sex in exchange for stories and that I should be raped.”

In response to criticism, government representatives at the hearing reportedly resorted to disinformation. A spokesperson for the Secretary of Institutional Communication of the Special Secretariat of Communication of the Presidency (Secom) said the Brazilian state was the victim of ideological persecution and accused the organisations present at the hearing of censoring journalists and experts who defend positions contrary to those recommended by the World Health Organisation.

In a related development, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) published a quarterly assessment of press freedom violations in Brazil in 2020, examining how President Jair Bolsonaro’s public vilification of the media affects the daily lives of journalists. Another report, by Article 19, said Brazil saw the sharpest drop in their freedom of expression score worldwide in the past decade. This decline accelerated with the coming to power of Jair Bolsonaro at the start of 2019, with an 18-point drop in one year. The organisation highlighted the wave of smear campaigns against members of the press, in particular against women journalists, often promoted by or even carried out with the support of public authorities.