Watchlist June 2020

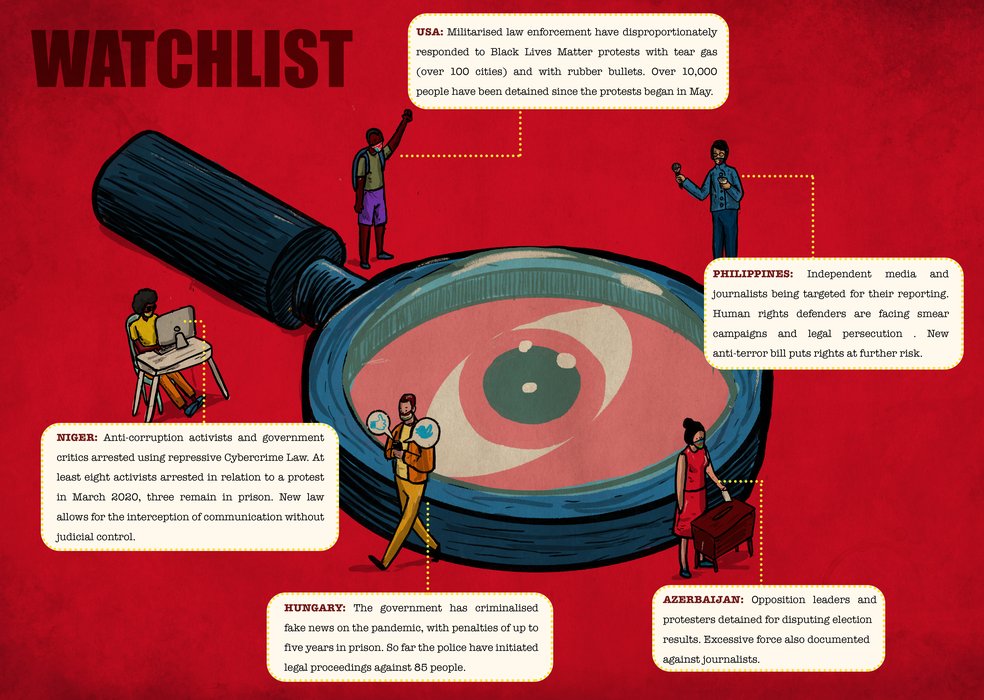

Latest Update: 29 June 2020 - The new CIVICUS Monitor Watch List highlights serious concerns regarding the exercise of civic freedoms in Philippines, Azerbaijan, Hungary, Niger and the United States of America. The Watch List draws attention to countries where there is a serious, and rapid decline in respect for civic space, based on an assessment by CIVICUS Monitor research findings, our Research partners and consultations with activists on the ground.

In the coming weeks and months, the CIVICUS Monitor will closely track developments in each of these countries as part of efforts to ensure greater pressure is brought to bear on governments. CIVICUS calls upon these governments to do everything in their power to immediately end the ongoing crackdowns and ensure that perpetrators are held to account.

Descriptions of the civic space violations happening in each country are provided below. If you have information to share on civic space in any of these countries, please write to monitor@civicus.org.

| Open | Narrowed | Obstructed | Repressed | Closed |

Philippines

Civic space rating: Obstructed

In response to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, the government declared a state of emergency on 25th March 2020 and granted President Duterte special powers by passing an emergency law. Among the provisions in the law is one penalising the spreading of "false information" online which could be used to curtail freedom of speech and silence the media. Journalists and social media users have since been targeted.

In what has been seen as another assault on media freedom, in May 2020, The National Telecommunications Commission, the country’s broadcast regulator, ordered ABS-CBN, the largest media network, to stop broadcasting after its 25-year franchise agreement with Congress expired. This has deprived citizens of critical information during the pandemic. ABS-CBN has long faced President Duterte’s ire for criticising his “war on drugs” and other policies. Further, in June 2020, prominent journalist Maria Ressa from Rappler was convicted for ‘cyberlibel’ in a case human rights groups have described as a politically motivated prosecution by the Duterte government.

Despite the pandemic, a new Anti-Terrorism Act 2020 is on the verge of being enacted that provides few safeguards against abuse and gives law enforcers exhaustive powers, including electronic surveillance, that could lead to discriminatory and arbitrary arrest and may result in prolonged detention without charge. Terrorism is defined vaguely and some believe the law has essentially been designed to target dissenters, not terrorists.

Activists continued to be red-tagged or arbitrarily arrested and accused of having links to the New People's Army (NPA), the armed wing of the Communist Party of the Philippines, because of their activism and their criticism of the Duterte government. The government has also frozen several bank accounts of NGOs on suspicion of “terrorism financing.”

Azerbaijan

Civic space rating: Closed

Immediately after the results of the parliamentary elections held on 9th February 2020 were announced, opposition representatives and citizens began to organise protests. This followed complaints by observers and opposition candidates, and the invalidation of results in several polling stations after results were disputed. On 11th February 2020, Azerbaijani police detained at least 20 people at a demonstration in Baku, where several participants were injured as protesters expressed dissatisfaction over widespread election violations.

On 12th February 2020, the OC-Media also reported that the police dispersed a spontaneous protest outside the Central Election Committee in Baku. A few journalists covering the protest were also injured.

The following week, more than 100 activists were arrested ahead of an unauthorised protest in Baku on 16th February. The protest was scheduled to take place in front of the Central Election Commission (CEC) building to denounce the election results. Several activists were picked up from their homes by authorities, while others were picked up outside the CEC building. Before this incident, the Musavat party, ReAl and D18 movements, as well as some independent candidates, had notified the Baku Mayor's office of their intention to hold a rally to contest the election results.

Protests continued in the days that followed. On 21st February 2020, a group of candidates for the parliamentary elections held a protest in front of the Central Election Commission against the head of CEC, Mazahir Panahov, blaming him for the disputed election results.

On 4th March 2020, Radio Free Europe reported that a journalist, Bahruz Aliyev, was punished while in prison for declining to vote in the parliamentary elections. He was allegedly confined to a special punishment cell at Baku’s Prison No. 13 for his refusal to vote, a claim which the country’s penitentiary service denied.

The Commissioner of the Council of Europe published a letter in early March addressed to the Minister of Internal Affairs of Azerbaijan, Vilayat Eyvazov, where she expressed concern at the violent dispersal of demonstrators in the election-related protests in Baku and the limitations imposed on freedom of assembly. The Commissioner called for investigations into the infliction of injuries on protesters and journalists as a result of excessive force by the police.

In the weeks that followed the violent dispersal and arrest of protesters over the disputed election results, as governments around the world took on strict measures and restrictions to curb the spread of COVID-19, Azerbaijani authorities were accused of misusing the pandemic restrictions to intensify the pattern of political retaliation through the systematic targeting of opposition supporters and critics, and punishing expression of opinion and speech.

In March 2020, authorities arrested and detained Tofiq Yagublu, a top opposition figure in the country on false hooliganism charges, while in mid-April 2020, it was reported that at least six activists and a pro-opposition journalist were sentenced to detention after criticising the government’s handling of the pandemic.

These arrests came just days and weeks after president Ilham Aliyev alluded to using the pandemic restrictions to crack down on the country’s political opposition in his address to the nation.

Hungary

Civic space rating: Obstructed

On 11th March 2020, Hungary declared a state of emergency due to the COVID-19 pandemic. While other European countries have also taken similar steps to tackle the pandemic, the Hungarian government led by Viktor Orbán has gone a considerable step further. On the 30th March 2020, the government passed the Bill on Protection against the Coronavirus, or Bill T/9790, now known as the so- called Authorisation Act, which extends the government's power to rule by decree, allowing it to prolong emergency measures and evade parliamentary scrutiny. Human rights NGOs have forewarned that the Authorisation Act has further exacerbated the deterioration of the rule of law and the state of democracy in Hungary. These concerns are echoed in a recent Freedom House report which found that Hungary is no longer a democracy.

In addition to introducing excessively wide powers without a sunset clause, the Act also criminalises spreading false information in connection with the pandemic, which could be punished by up to five years in prison. At the time concerns were raised that criminalisation of ‘fake news’ on the pandemic would lead to further censorship of independent media in Hungary and the erosion of media freedom. For example, prior to the act coming into effect, the Orbán government and the pro-government media accused independent media outlets of spreading so-called fake news, for example, reporting that Hungarian doctors and nurses lack proper protective gear.

Since the act was passed, police detained two people for spreading pandemic-related fake news in mid-May 2020. While the prosecutors decided to drop the cases against the two individuals, it is likely that such developments will have a chilling effect on freedom of expression. By 11th May 2020 police had initiated proceedings against 85 people for the dissemination of false information and inciting fear about the pandemic. While no journalists have been arrested thus far, they continue to face challenges during the pandemic. Critical questions posed by the independent media to the government tend to be ignored, more so than previously, and their access to information has diminished. These are concerning developments given that the state of media freedom in Hungary has been in regular decline. For example, in 2018 a pro-government media conglomerate (KESMA) was created, which was later found to be unlawful. The Hungarian Public media (MTVA) are forbidden from covering leading human rights organisations and independent media have been banned from Orbáns annual press conferences. Examples like these demonstrate that censorship against the media persists.

The day after the Authorisation Act was passed, the Orbán government tabled an Omnibus bill which sought to amend the Civil Registry Act to only recognise ‘sex by birth’- thus making gender recognition of transgender and intersex persons legally impossible. The amendments to Article 33 of the Civil Registry Act led to online protests during the pandemic under the #drop33. Despite the outcry from local transgender rights organisations and international human rights groups, the bill was passed by parliament on 19th May 2020 and signed into law by President Janos Ader on 28th May 2020.

On 18th June 2020 the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled that restrictions imposed by the Hungarian NGO Law adopted in 2017 breaches EU law. The law required NGOs to declare and register if they receive foreign-funding above €22,000. The court found that the law led to “discriminatory and unjustified restrictions”.

Niger

Civic space rating: Obstructed

In the past few months, Niger has seen a new wave of arrests and harassment of HRDs and those expressing dissent. At least 15 people, including eight civil society activists and leaders, were arrested between 15th and 17th March 2020 in relation to a protest against alleged embezzlement in contracts to purchase military material. Three of those eight HRDs remain in prison. Judicial harassment against anti-corruption HRDs continues through summonses, and arbitrary detentions, such as Ali Idrissa of the Network of Organisations for Transparency and the Budgetary Analysis and Publish What You Pay Niger on 9th April 2020 and woman human rights defender and president of the Bloggers' Association for an Active Citizenry on 10th June 2020.

Authorities have adopted repressive legislation, most notably the 2019 Cybercrime Law, that is actively used against HRDs and journalists. Recently, Niger's National Assembly approved, on 29th May 2020, a new law that authorises the interception of telephone communication in the context of the 'fight against terrorism and transnational crime'. The new law allows for the 'research' of information that may threaten state security or in the context of the fight against terrorism and organised transnational crime’.

Protests and meetings organised by civil society organisations have been nearly systematically banned by local authorities, often invoking the grounds of 'threats to disturb public order' or security grounds, referring to the context of insecurity due to terrorist attacks in the country. Certain of these bans have been made outside of the legal framework. The pro-democracy movement Tournons La Page documented at least 24 instances of protests and meetings being banned since March 2018.

Further civic space restrictions and violations have occurred in the context of COVID-19, including the arrest and prosecution of journalist Kaka Touda Mamane Goni for posting on social media on a possible COVID-19 case, and at least three people for having expressed criticism, including through private messages on WhatsApp, about the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the country.

These recent developments come as Niger prepares for legislative and presidential elections in December 2020.

USA

Civic space rating: Narrowed

Massive protests erupted in cities across the US following the death of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, by a Minneapolis police officer on 25th May 2020. A harrowing video from eyewitnesses shows the officer pressing his knee into the handcuffed man's neck for almost nine minutes while Floyd repeatedly said, “I can’t breathe.” Outrage over entrenched racial injustice and the country’s long history of violence against Black and Brown people by law enforcement brought hundreds of thousands to the streets across all 50 states. Protestors blocked streets, rallied, marched and chanted "no justice, no peace" and "say his name: George Floyd" while calling for an end to police brutality and demanding that law enforcement officers be held accountable.

Enduring pressure from demonstrations has brought important results, including charges brought against officers involved in George Floyd’s killing and commitment to reforming police practices from some authorities. But even as protests sparked important conversations about criminal justice reform and divestment from policing institutions, protestors in many cities were met with police brutality themselves. Militarised law enforcement wearing riot gear often resorted to disproportionate force to control crowds, indiscriminately using less-lethal weapons such as tear gas and rubber bullets. On 18th June 2020, a report by the New York Times showed at least 100 cities where tear gas was deployed despite many health experts questioning the use of this respiratory irritant chemical during the coronavirus pandemic. There have also been several reports of police ambushing protestors and using excessive force in detentions. Six officers were charged after a video surfaced of them repeatedly tasering and dragging two Black students out of a car.

Reports of property fires, looting and vandalism have been widespread, in particular during the first week of protests. Many authorities have fastened on a rhetoric that focuses on violent protest and unrest to delegitimise the demonstrations and justify the extensive use of force. President Donald Trump threatened to mobilise the military to put an end to the protests, blaming Antifa groups for the violence despite lack of evidence of any organised action by such activists. In a statement, Attorney General Barr announced that anti-terrorism powers would be used in response to civil unrest. By 3rd June 2020, over 17,000 members of the National Guard had been deployed in at least 23 states. Over 10,000 people have been detained in the protests, mostly for violating the curfews which multiple cities implemented to limit demonstrations. On 1st June 2020, over 300 people were detained in Washington DC alone for offences such as curfew violation, rioting and burglary. In addition, there have been reports of at least 11 people killed during the wave of protests.

430 incidents of assault against the press covering the protests have been registered by civil society, including cases of journalists detained and deliberately attacked. Mounting hostility against the press in the country has often been documented on the Monitor, with the public vilification of journalists by authorities, arbitrary bureaucratic restrictions imposed on the press, and several cases of harassment, smear campaigns and attacks against journalists from both state and non-state actors.