Peaceful Assembly

Women-led protests intensified in Mexico amid reports of killings of women and girls which captured the country’s attention. In particular, the murder and sexual assault of a seven-year old girl and the brutal femicide of Ingrid Escamilla triggered massive protests in and around Mexico City and other cities as people decried the increase in gender-based violence. Femicides have increased 137% in Mexico in the last five years, according to the country’s Department of Security.

On 14th February 2020, dozens of people demonstrated outside Mexico’s presidential palace, chanting “Not one murder more,” while a protester wrote “Ingrid” in pink spray paint on one of the palace’s doors. “It’s not just Ingrid. There are thousands of femicides,” said Lilia Florencio Guerrero, whose daughter was violently killed in 2017. “It fills us with anger and rage.” Yesenia Zamudio, a mother whose 19-year-old daughter was murdered, expressed her indignation with the government’s inadequate response and defended the acts of vandalism which have sometimes marked these protests: “I have every right to burn and smash things. I’m not going to ask for anyone’s permission, because I am doing this for my daughter.”

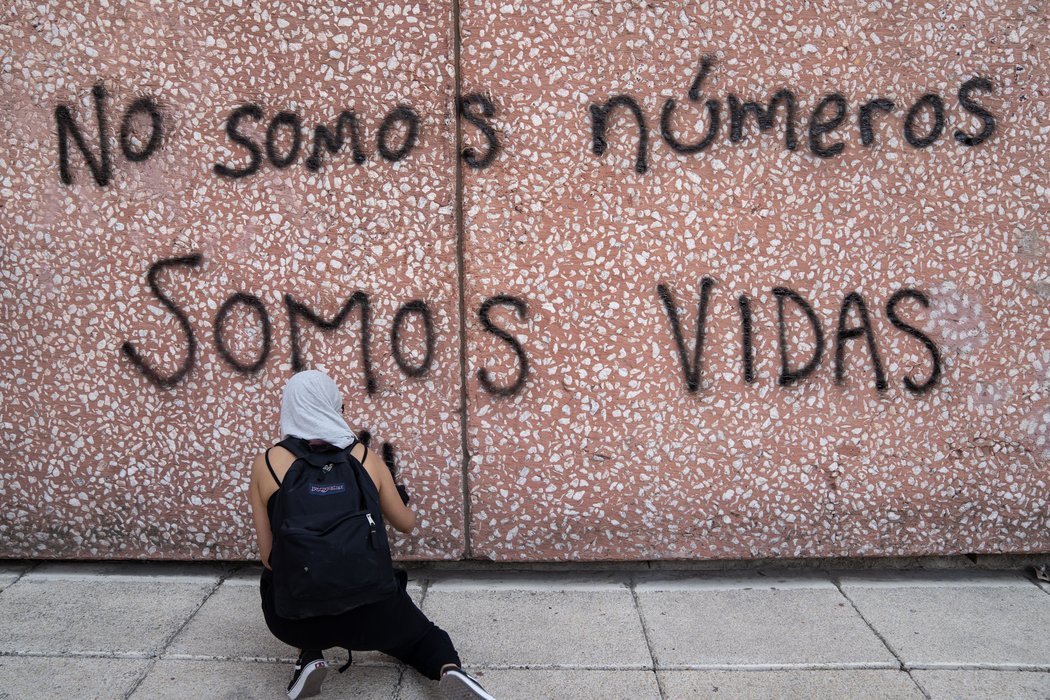

On 8th March 2020, nearly 80,000 women gathered in the streets of the country’s capital to call for an end to violence as part of the International Women’s Day march. Many in the crowd wore purple, the colour representing the feminist movement, and held signs of loved ones who were killed or missing. While most of the protests were peaceful, there were reports of vandalism to store fronts and government buildings spray painted with messages such as “misogynistic Mexico,” and “the president doesn’t care about us.” Clashes with counter protesters and episodes of violence reportedly left 52 people injured and 13 hospitalised in Mexico City.

Hoy las mujeres en México han decidido ir a paro y ausentarse del trabajo, de la escuela, del espacio público y hasta de las redes sociales como una forma de protesta contra una realidad cada vez más insoportable.#UnDiaSinMujeres #El9NadieSeMueve #ParoNacionalDeMujeres pic.twitter.com/VdvDJW977J

— pictoline (@pictoline) March 9, 2020

On 9th March 2020, women across the country stayed home as part of a general strike to protest rising violence against women and the government’s inability to address the crisis. Calling it Un Día Sin Nosotras ("a day without us") or "a day without women," thousands of women chose not to go to work, school and other events. The José Martí Institute posted photos online of half-empty classrooms, saying, "This is how our classrooms would be every day" if femicides continue.

In related developments, since October 2019 students of the National Autonomous University (UNAM) have staged multiple demonstrations and disrupted classes as part of their protest over the school’s failure to address gender violence and sexual assault. They also denounce that professors have used hidden cameras to secretly record female students while they were exercising or swimming, and demand the dismissal of several professors accused of harassing students. The protests, which include students from 23 of the UNAM colleges and preparatory schools, have largely been peaceful but there have been reports of violence. For example, on 4th February 2020, high school students marched to the Rectory’s office where some students allegedly smashed windows and threw incendiary devices at the building. Faculty has expressed solidarity with students, with several departments, including the Faculty of Political and Social Sciences and the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, calling on the school to address the students’ demands. However, according to news reports, some school and state officials have sought to undermine the movement and delegitimise the protesters, saying they have been organised by provocateurs and outsiders. Students and faculty of the university’s Social and Political Sciences department have continued to strike, even as classes have moved online due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Demonstrators occupy dam in Chihuahua

#Video 📹 Elementos de la Guardia Nacional arribaron a las instalaciones de la presa La Boquilla para iniciar la extracción de agua, esto causó el malestar de los pobladores https://t.co/U2SgNQVtlv pic.twitter.com/mhk7T7gwfo

— El Universal (@El_Universal_Mx) March 26, 2020

Upset over a government plan to divert local water to the United States under an international treaty, in the first quarter of 2020 hundreds of farmers and residents of Chihuahua municipalities demonstrated near major dam sites on the Conchos River. A treaty from 1944 determines obligations for both Mexico and the United States in managing cross-border flows of water, but locals say there isn’t enough water for both local farmers and the “water payments” dictated by the agreement.

In January 2020, protesters blocked local roads to obstruct access and reportedly took over a dam in the region. On 4th February 2020, new protests brought hundreds of farmers to demonstrate near the La Boquilla dam. Hundreds of protesters were able to get past the National Guard at the dam and refused to leave the property until the plan was suspended. While there were clashes between protesters and the security forces, the guards regained control of the premises on the following day. However, negotiations around the dispute continued and protests escalated. On 26th March 2020, demonstrators blockaded a federal highway and set vehicles from the National Guard and the National Water Commission (Conagua) on fire. According to news reports, one protester and two members of the security forces were injured in the confrontation. On 27th March 2020, Conagua announced it would not go through with the water diversion.

Protest against large infrastructure projects

On 21st February 2020, people in Mexico City demonstrated against large-scale infrastructure projects that they say will threaten their homes and the environment. According to the Associated Press, the protest gathered over 1,000 people and was joined by several groups including students, farmers and indigenous peoples. Demonstrators noted that the Maya Train project and others such as an oil refinery would harm residents and cause environmental damage to communities. The march also marked the one-year anniversary of the murder of Samir Flores, an activist who was advocating against a large gas-powered plant in Morelos state.

Expression

Journalists subjected to violence in protests

Media coverage of Ingrid Escamilla’s femicide in February 2020 triggered protests and attacks on local newspapers after some outlets published a graphic photograph of the young woman’s disfigured body. The protesters demanded an apology from daily newspaper La Prensa, which put the photo on its cover. According to news reports, some protesters spray painted one of La Prensa’s vehicles and set it on fire. In front of the media outlet’s offices, minor clashes were also reported between protesters and security forces. Newspaper Pasala was also criticised for using the photo on its cover, under the Valentine's Day-themed headline: "It was cupid's fault".

#NDI Momento en que una mujer de lentes oscuros lanza bomba molotov en Palacio Nacional que hiere y causa quemaduras de segundo grado a periodista Berenice Fragoso de diario El Universal. pic.twitter.com/LNqm79VbrM

— Raúl Brindis (@raulbrindis) March 9, 2020

In a separate but related incident, Berenice Fregoso, a photographer for El Universal, suffered second degree burns after a protester in Mexico City threw a fire bomb that exploded near journalists and other protesters during the International Women’s Day demonstration on 8th March 2020. A video of the incident shows the moment when a woman wearing sunglasses attempted to throw the explosive device at a group of anti-riot officers and it landed in the middle of a crowd. According to El Universal, Fregoso was hospitalised and diagnosed with second degree burns in her left arm, right leg and ankle.

On 19th February 2020, several members of the media were threatened and attacked while attempting to cover a protest over a land dispute at the Agrarian Court in Oaxaca. Article 19 reports that a journalist and photojournalist had recorded several people harassing two elderly people during a violent protest. According to Article 19, a group of about six protesters threatened the reporters and demanded that they delete the material. One woman allegedly held a sharp object to the journalist’s back. Both reporters managed to escape without serious injury but had to delete their recordings. Later in the day, more journalists arrived to talk with court officials but were confronted by a large group of demonstrators who attempted to take or damage their equipment. The journalists quickly left the scene but not before being threatened and attacked. At least four people were detained on 20th February 2020 for assault during this protest.

Police officers assault reporters covering demonstrations

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) is calling for an independent investigation into a series of attacks against journalists by police officers during a protest in Veracruz. On 11th February 2020, a protest outside a police station became violent after people reportedly attempted to enter the station. Police officers responded by attacking protesters and journalists, all of whom say they identified themselves as members of the media. One reporter says that police officers held a gun to their head and another recounts that officers handcuffed and dragged them on the ground. The journalists included Alberto Carmona, a reporter for El Pinero de Cuenca, Julia Santín and Brígido López from Los Llanos del Sotaviento, and Edna López from A Titulo Personal. Police also reportedly detained Sergio Herrera, a local radio journalist, and César Estrada, from El Noreste newspaper. “I was wearing a jacket with the word ‘press’ on it and had my credentials with me,” López later said. “There was no way they could have mistaken us for protesters.” While Veracruz’s Secretary of Government told news outlets that some of the journalists were “recruited” to document the protest, the state’s Public Security Secretary released a video statement acknowledging the incident and attacks.

"Baje su teléfono, nos están grabando" así la violencia por parte de policías municipales de Tapachula; una periodista detenida y vecinos, luego de la protesta pacífica en la que se pedía más seguridad y alumbrado público. https://t.co/e7fko6gJ8j pic.twitter.com/QH5G1yLdH2

— La Silla Rota (@lasillarota) January 28, 2020

In a separate development, on 27th January 2020, multiple reporters were attacked, detained or prevented from carrying out their work by police officers in Tapachula, Chiapas, while reporting on a public protest. A video of the incident shows officers wearing tactical gear and forcefully pushing protestors before the reporter holding the camera is also attacked. An independent journalist, Damian Sanchez, and Alejandro Gomez with Diario del Sur, say they were among the journalists assaulted by police and were both badly injured. Additionally, Cinthia Alvarado with Portal Revolution denounced that she was attacked, detained and had her equipment taken by police while covering the protests. According to Article 19, Alvarado may have been targeted because she had previously filed complaints about state officials.

Further cases of attacks and threats

On 29th February 2020, Cristian Pérez Ojeda, director of digital news media Sin CensuraNoticias, was reportedly held captive, threatened and assaulted by several armed men who made references to his journalistic work. Pérez Ojeda told Article 19 that he was walking with his wife in San Jose del Cabo, Baja California Sur, when he noticed a van full of men following them. The journalist says he tried to run but the kidnappers forced him into the van, where they threatened him with a knife, said his family was being monitored and asked about his work. “Who pays you to publish things against this administration?” his captors reportedly asked. Pérez Ojeda was taken to a vacant lot and assaulted until he eventually escaped and sought help. He was taken to the hospital by his family and filed a complaint with general state attorney’s office. The journalist had previously received a threatening message from a local official in January 2020.

On 12th February 2020, two reporters, including one enrolled in the federal programme to protect journalists, were threatened and attacked by members of security forces in Benito Juarez in Cancún, Quintana Roo. The two journalists were attempting to report on a shooting incident. Martín Ibáñez of Vanguardia de Veracruz and another reporter, whose identification was not made public for security reasons, were attacked by police and had their camera equipment damaged after officers questioned them for taking pictures. Martín Ibáñez was also injured on the abdomen and arm. According to Article 19, the second journalist’s assistance button was activated but officers involved in the incident prevented him from seeking help. They were let go after being detained for nearly an hour but not before receiving threats not to publish any of the photos they had taken.

On 20th January 2020, three journalists covering a public incident were reportedly assaulted and detained by state security forces in Michoacan. According to Article 19, the three journalists had finished documenting a confrontation between security forces and armed civilians when several officers stopped and questioned them. The officers then allegedly assaulted them and seized their equipment. Only one of the reporters, Minute by Minute’s Miasel Torres managed to show his press credentials to the police and was let go. The other two journalists, Ivan Cortes of Central Informativa and Angel Calderon of Mini Noticas, were arrested and taken to a police station. They were later released after being identified as members of the media.