Background

Greece recorded its first coronavirus case on 26th February 2020 and the government swiftly imposed a lockdown. In early March 2020, Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis announced a total lockdown in order to curb the spread of the virus. The relaxation of lockdown measures started in early May 2020. The tourist season officially began on 15th June 2020, with flights resuming for international travelers from 1st July 2020.

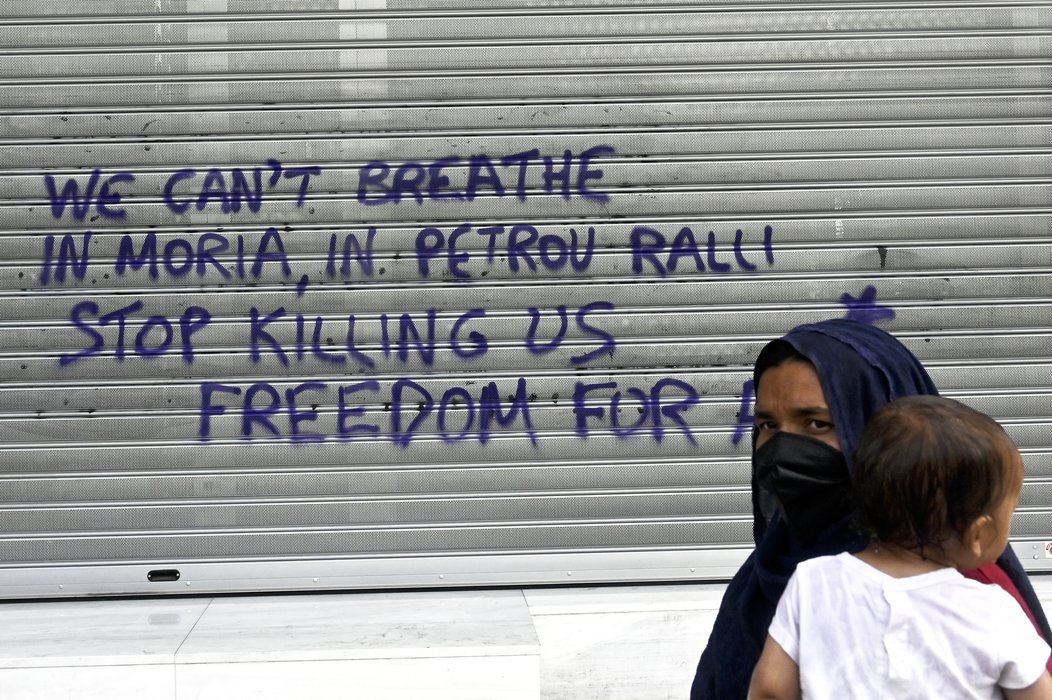

During the lockdown, like many other public services, the Greek asylum service’s operations were scaled back. The situation of asylum seekers in the country further deteriorated as they were put into unsanitary and crowded camps. Furthermore, despite opening its borders for travel the government announced that the lockdown for migrant camps would be extended by two weeks, thus leading to the further erosion of migrant rights.

Greece is struggling to cope with the increased number of asylum seekers arriving from Turkey following a decision on the 1st March 2020 from the Turkish government that it would no longer prevent people from trying to cross over to Greece. It is alleged that Greece illegally pushes back refugee boats to Turkish waters.

Association

During the first half of 2020, several additional registration and certification requirements were introduced by the Greek parliament and the government for NGOs working with immigrants (Law No. 4662/2020, 7 February 2020; Ministerial Decision 3063/2020, 14 April 2020; Article 58 of Law 4686/2020, 12 May 2020).

Law No. 4662/2020 sets out new general requirements for the registration of NGOs working in areas of asylum, migration and social inclusion. The law makes provision for an NGO registry which contains information not only about the organisation itself but also on its members, employees and associates. The Ministerial Decision sets out conditions for the registration (and often re-registration) and for the certification of NGOs. Article 58 of Law 4686/2020 stipulates further details on the legal requirements for NGO registration, making it clear that only registered NGOs can undertake activities in the field of asylum, migration and social integration.

In February 2020, government spokesman Stelios Petsas told reporters that the new regulations help the government to “control the activities of hundreds of NGOs operating in Greece” which is needed as a number of NGOs supposedly helping asylum seekers operate in a “faulty and parasitic manner”. Such a statement did not come as a surprise, as Greece's ruling party politicians have repeatedly vilified NGOs who work on asylum issues, with labels such as smugglers and people traffickers.

Several civil society organisations, international organisations and legal experts found the new legal developments worrisome. Many believe that the law is yet another politicised attempt to curtail asylum.

The new regulations have several highly problematic provisions that may create a chilling effect on NGOs working in the field of immigration. Furthermore, they are not in line with the European standards and the Greek Constitution, for the following reasons:

- First, the registry is to be overseen by a specially appointed secretary (not independent from the government) who can revoke or reject registrations, even if all the legal requirements are met. This gives uncontrolled power to a state body over civil society actors.

- Second, as Nassos Theodoridis, Athens office manager of Antigone and attorney-at-law told CIVICUS Monitor, the obligatory revelation of names, addresses and e-mails of the members of NGOs required by the Ministerial Decision “could be regarded as inconsistent with the constitutional principle of proportionality”.

- Third, Lorraine Leete from the Legal Centre Lesvos told CIVICUS Monitor that new regulations place “onerous accounting obligations and restrictions” on the operation of NGOs working with migrants. This is “particularly concerning” as these may “prevent small Greek organisations from continuing to operate”.

After reviewing the developments, the Expert Council on NGO Law of the Conference of INGOs of the Council of Europe stated that:

“The reduction in civil society space in the areas of support to refugees and other migrants may produce a worrying humanitarian situation, given the significant needs of this very vulnerable population and already existing gaps in service provision by government and others, and the continued violence and judicial harassment such NGOs face, including criminalisation of aspects of their work.”

The Expert Council recommends that the legislative provisions in question “be substantially revised so that they are brought into line with European standards.”

In addition to the above, the Greek Minister for Immigration and Asylum in April 2020 introduced a bill titled “Improvement of Migration Law” which makes provision for the systematic detention of asylum seekers whose appeals have been rejected. In addition, it allows the substitution of open refugee camps on the islands with ‘closed controlled centres’. In a statement Amnesty International called on the Greek government to protect migrants and asylum seekers in Greece.

“Forcing groups of people into confined and often overcrowded spaces is not the behaviour of a responsible government amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. This new law is not only dangerous for detained people’s health, it goes against international law under which migration detention should only be used as a last resort,”- Adriana Tidona, Migration Researcher at Amnesty International.

Peaceful Assembly

The following protests took place during the reporting period:

- World Refugee Day protests: About 2,000 people gathered on World Refugee Day on 20th June 2020 in Athens to protest against government’s anti- migrant polices, specifically in relation to migrant evictions. Anti-racist groups, joined by refugees from migrant camps, held banners reading "No refugee homeless, persecuted, jailed".

- Black Lives Matter protests: On 3rd June 2020, following mass protests against racism in the US after the death of George Floyd, a Black man, by a Minneapolis police officer, thousands gathered for a Black Lives Matter (BLM) protest to the US embassy in Athens in support of anti-racism and anti-fascism. While the march was peaceful, police report that tear gas was used to disperse protesters at the embassy after rioters attacked the offices of the embassy.

Thousands protest #BlackLivesMatter in Athens, march to the #USA Embassy. #Greece pic.twitter.com/LLIo0UF1Cu

— Savvas Karmaniolas (@savvaskarma) June 3, 2020

Right to protest restricted by new law

On 29th June 2020 the Greek government announced plans to put in place tighter restrictions on demonstrations through its New Democracy bill, which aims to regulate street demonstrations. The country has a long tradition of public protests, where demonstrations are the main way in which people express their disagreement with government policies or local regulations. Solely in the capital, Athens, there were 80 protests held in May 2020.

The government argued that the draft legislation submitted to parliament would protect the right to protest and stop the frequent disruption to traffic and city-dwellers’ experience. According to the draft legislation, participation in a demonstration held without police permission would become punishable by up to a year in prison. In addition, protest organisers would be held liable for damage caused to public or private property during a protest.

Unsurprisingly, many found the government plans unacceptable. On 2nd July 2020, thousands rallied in central Athens. Demonstrators asked for the bill to be withdrawn. Some held banners calling it an ‘abomination’.

On 6th July 2020, presumably due to the criticism received, Citizens’ Protection Minister Michalis Chrysochoidis introduced a series of improvements to the bill. Under the new version of the bill, the police will need to secure the approval of a first instance court judge to prohibit gatherings from taking place, and approval from a prosecutor to break them up. The provision that would see participants of banned gatherings facing prison time was scrapped.

On 9th July 2020 the Greek parliament passed the law. Ten thousand people gathered outside parliament, with banners stating, “hands off demonstrations”. It’s reported that a separate group broke away from protesters and began throwing petrol bombs and the police retaliated with tear gas.

Clashes in Athens during a big demonstration against a government's new law posing restrictions on street protests. #Greece pic.twitter.com/D7DMA2m4en

— Savvas Karmaniolas (@savvaskarma) July 9, 2020

Expression

In March 2020, several governmental decisions regarding the media were criticised for their lack of transparency, among them suspending broadcasting fees and an 11 million Euro publicity campaign package related to promoting COVID-19 measures.

“Support for the media is necessary, but distributing money in a habitat like that of the Greek media, which is notorious for its lack of transparency and clientelistic relations, without making clear immediately who gets what and why, is a very serious issue,” Greek journalist Yannis-Orestis Papadimitriou, a member of an investigative journalists’ consortium called The Manifold told BIRN.

“It is even more worrying when that happens in a situation in which media, their owners, who are also involved in other sectors of the economy, and the political class have proved to be co-dependent in many ways,” he added.

In addition, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) reports that in April 2020 government published a decision which prevented hospital staff from speaking to the media and that Greek journalists need to obtain permission before reporting inside hospitals.

In an independent development in March 2020, several journalist associations urged the EU and member states to take swift action to create a safe environment to protect journalists, freelancers and bloggers who are reporting on the current situation of asylum seekers in Greece. According to the joint statement, reporters in Greece currently face physical attacks, online harassment and censorship. The statement read:

“A safe environment is essential for journalists to perform their role as watchdogs of democracy. The current situation in Greece is symptomatic of the severe threats to press freedom witnessed by media freedom organisations within the EU. It does not only have a harmful impact on journalists’ working conditions, but also restricts citizens’ access and right to information.”

In a separate development, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reports that two bombs exploded outside the Athens offices of the Skai Media Group. No one was injured and the bombs caused minimal damage to the offices. In a statement, the group Anarchist Comrades confessed that they were behind the bombings. They called the Skai Media Group the “unofficial press office” of the current conservative government in Greece.

Greece’s rank remains unchanged this year, at 65th place on the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index 2020, released in early April 2020.