Association

The right to freedom of association is protected under the South Korean constitution and the administration of President Moon Jae-In has generally respected this right. However, issues persist over the denial of registration or revoking of certification of certain trade unions.

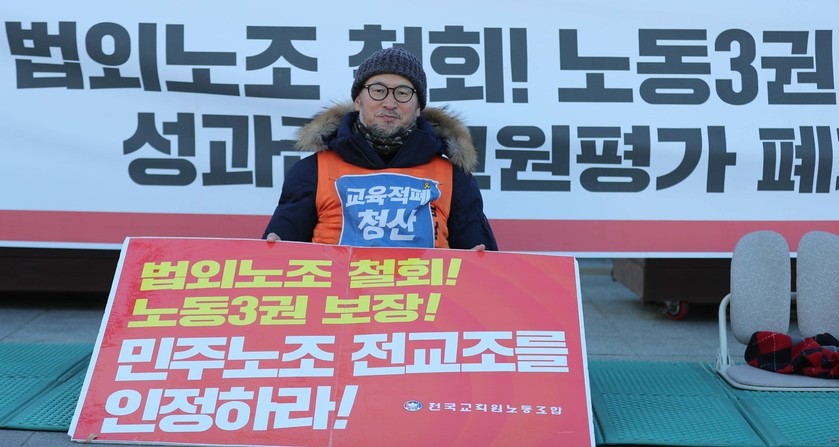

On 4th December 2017, Cho Chang-ik (photo above), the chairperson of the Korean Teachers and Education Workers Union (KTU), began a hunger strike demanding the government restore KTU's legal status. KTU had been legalised in 1999, but later deprived of its registration because it allows teachers who have been fired to remain as members. It has filed a lawsuit in the Supreme Court for its legal status to be reinstated after losing an appeal in the district court. The Korean Government Employees Union (KGEU) has also been repeatedly denied its registration as a union because of the same issue as KTU has faced.

In June 2017, the International Labour Organization (ILO) recommended that the South Korean government amend the Education Workers Union Act and the Government Employees Union Act. These Acts contain provisions by which the courts have been able to justify decisions to not recognise or register the KTU and KGEU. The ILO statement to the government reads that both Acts

“...deprive terminated workers of their right to be union members [and] rob workers of their right to voluntarily enroll in organizations. As such, these constitute a violation of the principle of the freedom of association. Since the judiciary and government will continue to deny the legal status of the KTU and the KGEU as long as these legal provisions remain in place, we once again strongly urge the government to abolish these provisions”.

In a separate development in November 2017, service workers in the supermarket industry announced their plan to establish a joint industrial union. The newly-formed Mart Industrial Labor Union Organizing Committee will work to unify workers at Lotte Mart, Emart and Homeplus under one industrial union. Out of the 500,000 workers in the supermarket industry, only 85,000 are “regular workers” directly employed by the supermarkets. The majority are irregular workers hired through a web of subcontracting firms to perform high-intensity physical labour for subpar wages. Irregular workers have little labour protection and are denied the right to organise.

Expression

Accusations of political bias are rife in the country’s public broadcasting sector. In September 2017, two of the three major broadcasters went on strike to demand independence for reporters.

今朝のKBSニュース韓国KBSの社長が労組により解任、後は大統領の承認をえるだけ。ぐぐっても記事がでてこないが去年からの労組の抗議の結果?→SOUTH KOREA: KBS and MBC Union Workers go on strike https://t.co/s9INp1wIsL日本NHKは公共放送税金投入なのに偏向報道でも会長退任もない

— そら 脱被爆・脱原発 (@soraazure) January 23, 2018

South Korea’s Munhwa Broadcasting Corporation (MBC) employees went on strike on 4th September calling for the resignation of MBC's President Kim Jang-kyom and demanding greater independence from political interference. The strike ended in mid-November following the dismissal of the president for allowing former South Korean President Park Geun-hye to influence MBC’s operation

Employees from South Korea’s other public broadcaster, the Korean Broadcasting System (KBS), also went on strike on 4th September, with their union calling for the dismissal of its head Ko Dae-young, as well as justice for journalists who have been unfairly dismissed, transferred, suppressed, or faced disciplinary measures. The strike ended on 23rd January 2018 after the public broadcaster’s board of directors approved a motion to dismiss its president.

Peaceful assembly

On 12th November 2017, the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU), the second largest trade union in South Korea, staged a mass rally for the first time since the new government took office this year. About 30,000 protesters took to the streets to demand substantive social reforms under the new government and called for more collective actions among workers.

On 7th November 2017, thousands gathered in the centre of Seoul to voice disapproval of U.S. President Donald Trump’s visit who came to the country amid concerns over North Korea’s nuclear threats. According to the National Police Agency, more than 15,000 police officers were deployed to provide security during Trump’s visit. The police attempted to ban a march in the streets near the presidential Blue House. However, the Seoul Administrative Court ruled that such a ban would infringe on the right to peaceful assembly. The riot police also installed a wall of police buses to barricade the protesters. A coalition consisting of over 200 civil society organisations condemned the attempts to disrupt the protests using the bus barricades.

On 2nd December 2017, the Joint Campaign to Legalize Abortion, comprised of 11 civic groups including Womenlink and the Korea Women’s Hot Line, organised the “Black Protest”. The “black protesters” want to put an end to South Korea’s outdated abortion law, which activists argue places most of the burden on women who face the social stigma and shame surrounding abortion. The protests began in September 2016, when the Ministry of Health announced that doctors who perform illegal abortion procedures will receive stronger punishment, meaning that their licenses can be suspended for as long as 12 months. In November 2017, the president committed to reviewing the country’s 64-year-old law to ban abortion after receiving a petition signed by 235,000 people. However the government appears to be using tactics to postpone its review.